Smiling from ear to ear: A book review

“Matilda” and “The BFG” by Roald Dahl are two of my all-time favorite books. They make me happy. They also make me laugh till my belly hurts. But then so do “The Twits”, “James and the Giant Peach”, and “The Witches”. Dahl’s writing weaves a spell and takes you into unique, captivating worlds from where you never want to leave.

Fun fact: almost every book by Dahl has a song or verse. Not counting nursery rhymes, it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that Dahl’s books are where I first got introduced to poetry. These aren’t regular poems. Laced with humor and lessons, they are little stories in their own right. So, you can imagine my delight when I stumbled upon a copy of “Songs and Verse” at Ekta Bookstore in Thapathali, Kathmandu, when I was browsing through their children’s section recently.

[Disclaimer: I don’t have children but I can often be found at bookstores hunting for a fun children’s book or two. There’s a certain charm in rediscovering children’s books as an adult. Surprisingly, it can give you new perspective on things. Children’s books are filled with important life lessons and they can be quite comforting too.]

Songs and Verse has seven sections—with rhymes about magical creatures, monsters, and dreadful children as well as adults. If you have read and loved Dahl books, you will be familiar with many of the poems in this collection but there are also some previously unpublished works that are delightful. There’s a verse that Dahl didn’t include in “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” because he felt he had created just too many ghastly children and that there was simply no room for one more.

The book has a foreword and opening illustrations by Quentin Blake, who has previously illustrated 18 of Dahl’s books. The publisher has also roped in many talented young illustrators as well as award-winning artists such as Babette Cole, Lauren Child, Chris Riddell, Alel Scheffler and Tony Ross, to name a few, to work on the book. The end result is a fascinating hodgepodge of stories that jump out of the pages.

I have taken to reading a verse or two at bedtime and I love it. It’s how I unwind. No matter how difficult things have been, Dahl’s verses reassert life’s beauty and remind me of the importance of finding joy in the little things. It helps end the day on a positive, merry note, and I go to sleep smiling.

Published: 2005

Publisher: Puffin Books

Language: English

Pages: 191, Paperback

Five books to snuggle up with

Winter weekends are for basking in the sun, all snuggled up on comfy cushions with a soft blanket and a hot cup of tea. It’s also a good time to read some old favorites that you know will leave you with a warm, fuzzy feeling. Here, I share with you my winter (re)reading list.

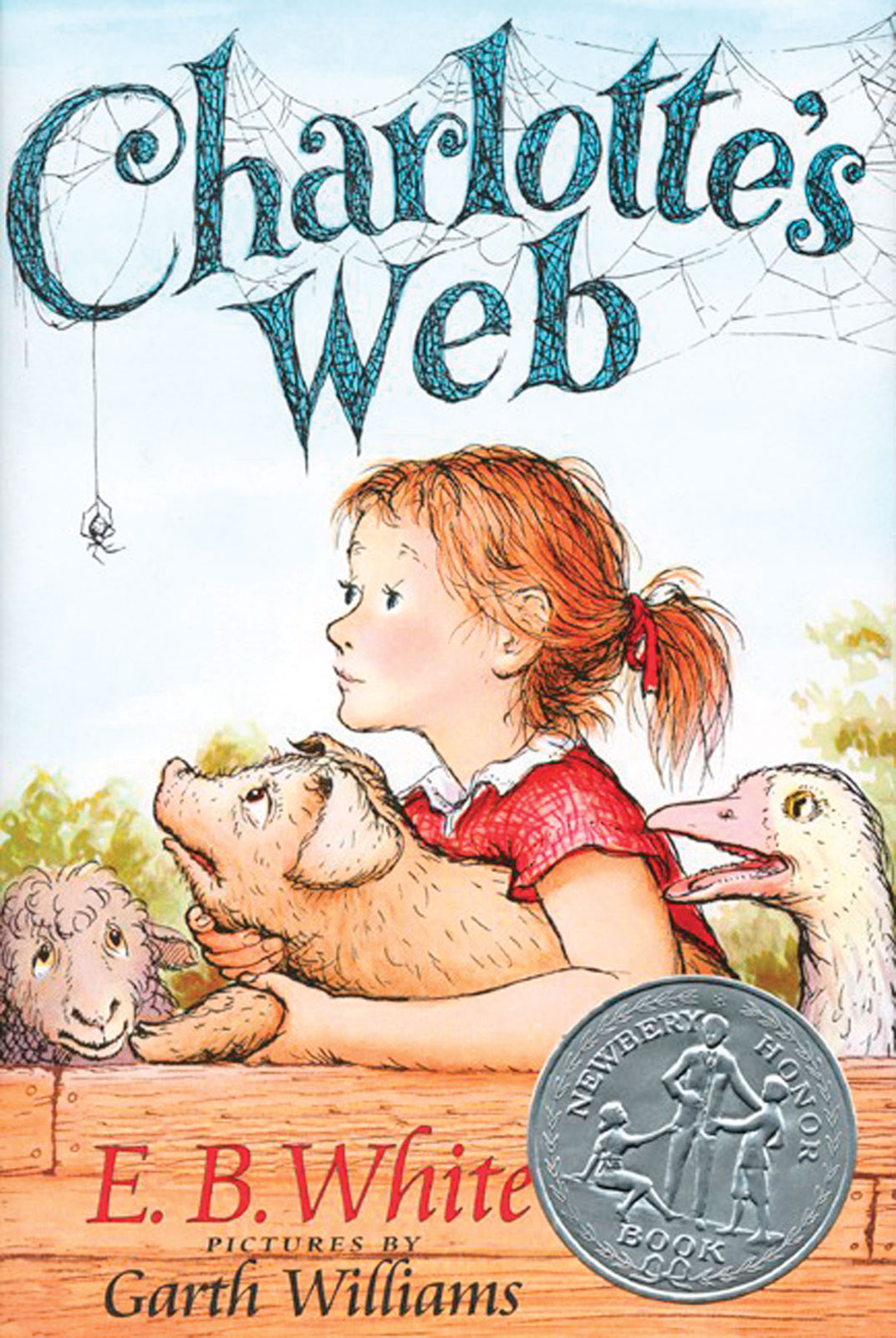

Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White

This children's classic begins with the main character, a young pig, almost getting slaughtered by a farmer. But Fern, the farmer’s daughter, convinces him not to kill the pig and names him Wilbur. Wilbur goes on to live in a barn that belongs to Fern’s uncle where he befriends a gray spider named Charlotte. When Wilbur finds out he’s on the next Christmas dinner menu, Charlotte comes up with a plan to save him. This powerful book on what it means to be a good friend and love someone wholeheartedly is just the kind of cheer you need on a sunless day. The good thing about this book is that you can read it in one sitting and then you can read it over and over again.

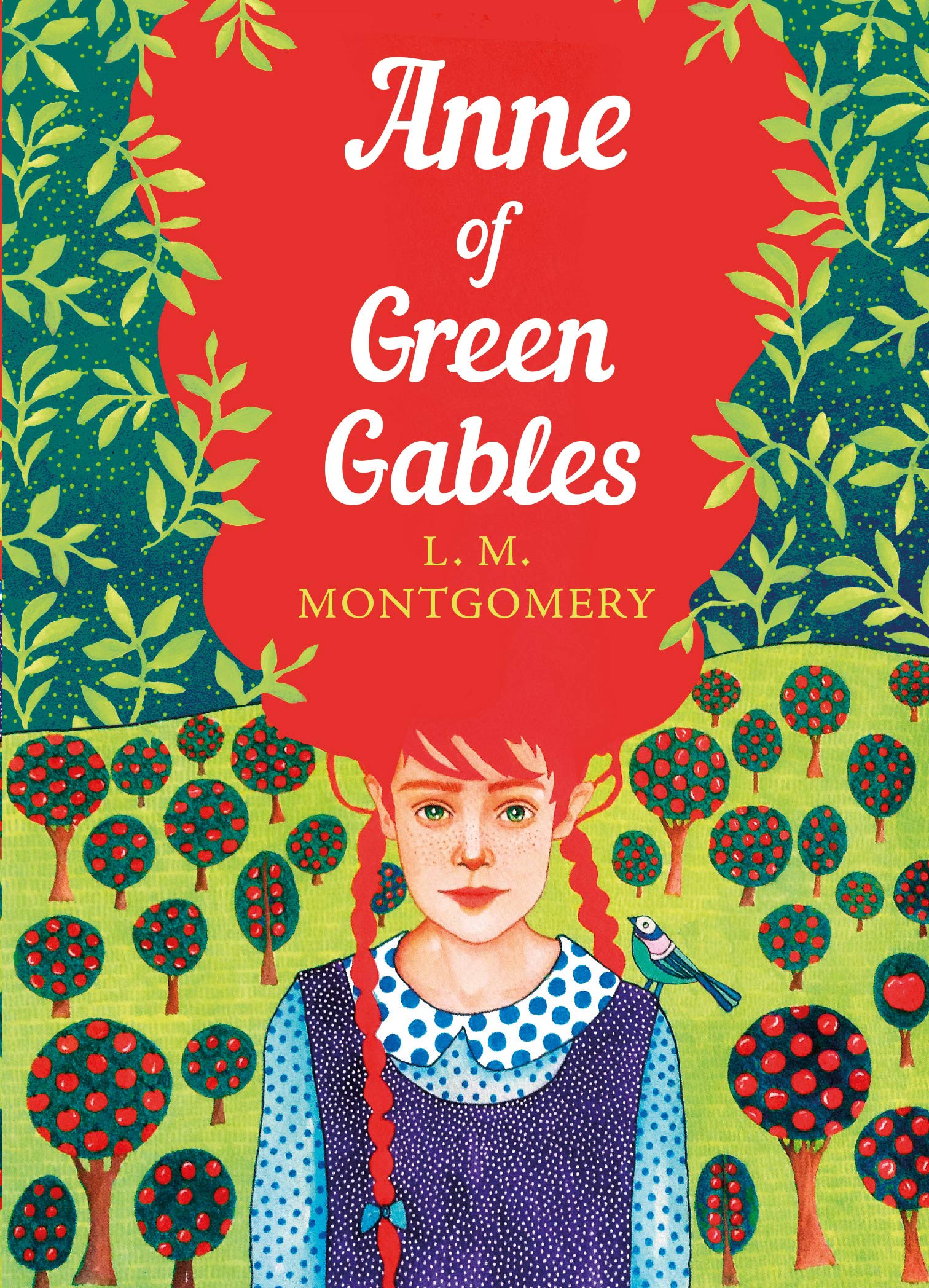

Anne of Green Gables by L. M. Montgomery

I read Anne of Green Gables and its seven sequels when I was in school and I remember being fascinated by the protagonist. She was kind and she was funny but she was also like every other rebellious girl her age—falling off roofs and dyeing her hair green. There is a lot the free-spirited 11-year-old Anne Shirley can teach you about love, family, friends and life in general. The novel has sold over 50 million copies and has been translated into at least 36 languages. Anne of Green Gables takes you back a couple of decades but the message is as relevant today as it was when it was first published in 1908.

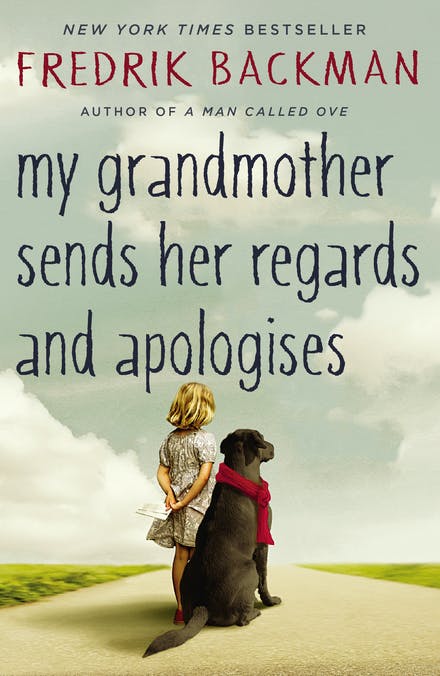

My Grandmother Sends Her Regards & Apologizes by Fredrick Backman

Elsa is “almost eight years old” and her best and only friend is her grandmother. Upon her death, she leaves Elsa a series of letters to be delivered to their intended receivers. The main purpose of each letter is to say sorry to the receiver. The book is basically Elsa’s journey and discoveries along the way as she goes about her mission of delivering the letters. Backman’s writing is amazing. Elsa is fascinating. And the story is just the right amount of romp and melancholy. You won’t be able to put this one down.

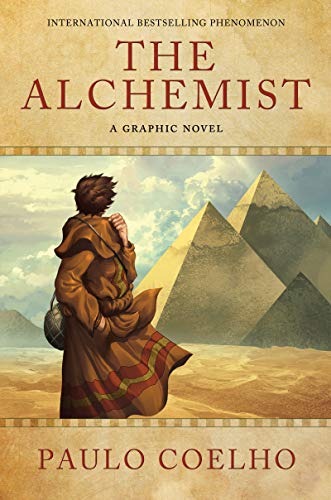

The Alchemist, A Graphic Novel by Paolo Coelho

I can’t believe I’m recommending The Alchemist. I didn’t find the story engaging even though it became an instant bestseller. But the graphic novel is super fun and makes the story a whole lot more interesting than it actually is. Coelho himself said the graphic novel exceeds his expectations and is a beautiful manifestation of what he originally imagined while crafting the story. If you already know the story, you can just dip in and out of this and watch scenes come alive before you.

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

I don’t usually underline sentences or highlight passages when I read. Bird by Bird is the one book where I’ve written on the margins and gone crazy with highlighters in different colors, on almost every page. This is also a book that I pull out when I need some perspective. It’s a treasure trove of contemplations that are timeless. Though essentially a guide on good writing, Bird by Bird is also crucial life advice by one of the finest writers we have today. You don’t have to read this book cover to cover. A chapter here and a page there is enough to get you thinking and looking at things a little differently than before.

A book for all seasons: A book review

“All the Light We Cannot See” by Anthony Doerr has a piece of my heart, one of those books that makes me sigh whenever I see its spine on the bookshelf. I wish I could forget every word I read and then discover it all over again. The winner of the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for fiction tells the story of a blind French girl and a German boy as they try to survive the devastation of the Second World War. It’s heartbreaking. It’s beautiful. Doerr’s language casts a spell.

I came across “Four Seasons in Rome” as I was hunting through the shelves at Pilgrims Bookstore in Thamel, Kathmandu, looking for something fun and uplifting to read. I’d had a rather long bout of bad luck with books. I was sure Doerr would get me out of the rut. He did. And how.

Anthony Doerr

Anthony Doerr

Four Seasons in Rome is a memoir/travel book about a year in Doerr’s life after he wins a prestigious award. The prize is a year in Rome with a writing studio and an apartment at the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He gets the news on the day his wife gives birth to twins. As he was already researching for what would go on to become the bestselling novel, All the Light We Cannot See, he figures he could use a year to sit down, focus, and write. So, the couple moves to Rome when the twins are just six-months old.

This relatively short book (compared to his other works) is a breezy read, one that takes you into the heart of fascinating alleyways, sweet-smelling bakeries, and stunning architectural marvels of Rome. It makes you want to get on the next flight to discover the city for yourself. His detailed descriptions paint a vivid picture and you want to be there, taking it all in.

Though the book is mainly about Rome and navigating life in a new city where everything feels foreign yet familiar at the same time, it’s also equally about parenthood, the bittersweetness of life, and the ultimate truth that everything is impermanent. Doerr keeps reminding you that life is “sweet, made sweeter because of its impermanence”. His words wash over you and often succeed in getting you to put the book down and take a minute to be grateful for all that you have.

However, Doerr’s strongest point is the way he writes. He isn’t writing to impress. He keeps things simple, which is often the hardest thing to do when writing. It keeps you engaged and intrigued. Reading Four Seasons in Rome is like having a one-on-one conversation with the author—one that has you falling in love right from the start.

Biography

Four Seasons in Rome

Anthony Doerr

Published: 2007

Publisher: 4th Estate

Language: English

Pages: 210, Paperback

A reader’s life, explained

I hoard books and I cannot lie. This is the one habit that probably helped keep me sane during the lockdown. However, all my life, I’ve had to deal with inquisitive family members and friends who wondered if I actually read all the books I bought or if I was simply showing off. In my defense, I eventually get around to reading at least 70 percent of the books I buy.

But, really, who, no matter how voracious a reader, reads every single book they buy? That doesn’t mean we buy books to fill up our bookshelves or post pictures with them on Instagram. Readers will agree that when we buy books, we have every intention of reading each one of them. It’s just that invariably we will go out and buy more books before we have finished the previous selections. That’s just how it is.

My habit of hoarding books started during childhood. Now, I will conveniently shift the blame on my dad. While he never let me have more than one chocolate or one toy whenever we went out shopping, my dad never set a limit when it came to buying books. He would let me pick as many as I wanted. Sometimes, I wanted a dozen—comics and books both. And I got them. I don’t ever remember a time we went to a bookstore and I walked out with just a book.

Now that I’m married to a voracious reader, the hoarding has gotten worse—there are two of us doing it. We probably spend a major chunk of our salaries on books, when we travel most of our luggage is filled with books, and we gift each other, and our friends, books at almost every occasion.

Both of us also enjoy sharing what we are reading. We post about our vacay book hauls—piles that are at least two- to three-feet high and weekend reads on social media. The response is almost always along the lines of: “How do you find the time to read all this?”, “Do you actually read them all/really fast or are you just posting to make people jealous?” and an indignant, “No one can read this fast. You were reading something else two days ago.”

The thing is when you love to read, you cannot not read. I always need a story in my head. I’ll go crazy otherwise. Every family has its drama and, to make matters worse, I don’t necessarily like people. Thinking of these fun fictional characters gives my brain the break it needs from the theatrics of daily life. So, I read—compulsively, obsessively. I read on the stationary bike. I read during commutes—when the car’s stalled and I can put the vehicle in neutral. I read during tea breaks when my colleagues are busy ‘catching up’. I read whenever I can, even if it’s just for 10 minutes.

Sometimes, I read a book in a day, other times it takes me a couple of days and some books I finish in a week or a month. And while I definitely buy more books than I could ever possibly read, every book I haven’t gotten around to reading and is gathering dust on the bookshelf is on my to-read list. And no, I’m not posting photos of one book after another just to get on your nerves—just like you aren’t posting food or cocktail hours photos to get on mine.

Good plot wasted: A book review

At bookstores, I’m always thrilled to come across debut novels. Sometimes, I even squeal a bit with joy. Though there haven’t been many debut books I have loved, every time there’s a book by a new author in the market I’m filled with nervous excitement. It’s also amazing how debut novels come with dust jackets filled with over-the-top claims by bestselling authors. ‘Darling Rose’ by Stephanie Wrobel has the likes of Lee Child and Lisa Jewell calling it “sensationally good” and “absolutely brilliant”. And it had a pretty cover too.

But I should have learnt my lesson by now and not judged a book by its cover. Touted as a thriller that explores the relationship between parents and children, more specifically a mother and a daughter, Darling Rose is dull and predictable. It could have been interesting had the author focused on either making the plot more fast-paced or developed the characters a more. With neither engaging plot nor fascinating characters, the book fails to impress.

_20201110150851.jpg)

I have to say the premise held promise. It was unlike anything I had ever come across. For 18 years, Rose Gold Watts, daughter of Patty Watts, believes that she is sick and needs the feeding tube and surgeries to stay alive. Turns out, Patty has been poisoning her own daughter to make sure Rose Gold can never live without her. All Patty ever wanted was to love someone and be loved in return. Also, she craves the attention she gets as a single mother of a sickly child. Then, she is sent to prison for aggravated child abuse. Rose Gold’s testimony is key in her sentencing.

After five years, Patty is ready to put old grievances behind and Rose Gold, who didn’t talk to her mother for a few years of her jail term, also wants to mend their relationship. She even agrees to let Patty live with her and her son, Adam. But nothing is as it seems. Patty still seems to seek control, if not of Rose Gold, then of Adam. And Rose Gold isn’t as meek as she once used to be and she might not have forgiven Patty.

Wrobel came up with an intriguing idea but couldn’t do it justice. Darling Rose Gold is a colossal waste of a good plot as Wrobel fails to evoke drama and tension in her writing. There is absolutely no suspense. Things are exactly how they appear to be. Even the twist in the end—which you see coming—does nothing to salvage the story. It’s good writing, in bits and pieces, but that’s about it.

Fiction

Darling Rose Gold

Stephanie Wrobel

Published: 2020

Publisher: Michael Joseph (an imprint of Penguin Books)

Language: English

Pages: 345, Hardcover

Never felt sadder: A book review

‘A Little Life’ by Hanya Yanagihara will break your heart into a million pieces and, as theatrical and clichéd as it may sound, you will feel like life will never be the same again. There is no way these characters are leaving you. They will inhabit every possible space in your head and whenever someone says you look a little lost, it will be probably because you are thinking of them, wistfully, and brimming with love.

Ever since I finished it a few days ago, I’ve recommended it to most of my friends, asked my husband to read it at least twice a day, and picked it up numerous times just to hold it and stroke the pages. This, I know, makes me sound like a lunatic, but Yanagihara has really messed with my head.

The book had been on my bookshelf for over four years. Meanwhile, I read everything there was being written about it, watched booktubers bawling their eyes out while reading it (check out paperbackdreams on YouTube), and low-key stalked Yanagihara on social media to try and find out just how her brain functions. Recently, a friend/reader/writer I admire (find her @15n3quarters on Instagram) mentioned Hanya Yanagihara as her favorite author and I finally dusted the book—shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize 2015—off my bookshelf.

A Little Life is about four friends—Jude, Willem, Malcolm, and JB—who move to New York after college. They are broke and clueless but all are ambitious and have one another for support. The story revolves around how their lives and friendships change over the years. However, for the most part, it’s about Jude who goes on to become a successful lawyer but is traumatized by his abusive past.

There are also other characters like Harold and Julia, Andy, and Richard whose backstories we never get to know much. Though the book isn’t essentially about them, Yanagihara hasn’t crafted characters without making them imperative to the narrative. So they too end up taking up considerable mind-space once you finish the book. It’s not often that a book has had this kind of effect on me. But A Little Life had me thinking about its villains as well and contemplating why they did what they did.

At 700-odd pages, the masterpiece is a long read. But the character-driven book, typeset in a font that’s not really friendly to the eyes, will consume you, and when you get to the end, you will want to hug the book and sob your heart out. Then, randomly flipping the pages, you will hunt for clues you might have missed, and wish you could have saved at least one character, and wonder how that might have changed things for all of them. This is where I am at. And this is where I will probably be for the rest of eternity.

If all that I have said here sounds melodramatic then read A Little Life and I’m sure you’ll see where I’m coming from.

Fiction

A Little Life

Hanya Yanagihara

Published: 2015

Publisher: Picador

Language: English

Pages: 720, Paperback

Why I read the Bhagavad Gita

My earliest memory of the “Bhagavad Gita” is a worn-from-use, spine-twisted, hardcover copy of the epic my grandmother kept on a dressing table—which would later go on to become a family heirloom. She was always quoting verses and it seemed no matter what we did, there was something in the Bhagavad Gita to either justify or condemn our actions.

My grandmother was forever thumbing through her much-revered copy. She would even run her hands over the words as she watched TV or talked to us. As a kid, I was fascinated by that particular slightly oily copy of the Bhagavad Gita that seemed to hold the universe’s secrets within its pages. Also, that it was a conversation between the avatar of Vishnu, Lord Krishna, and a prince named Arjuna had me wanting to know exactly who said what.

It was only years later, when I was in high school, that it occurred to me that my grandmother was using the Bhagavad Gita as an excuse to get us to behave how she saw fit. Afterall, how could she know for sure what was written in it when she couldn’t read? Everything she said was derived from someone else’s words, interpretations, or whatever she thought was right.

I used to tell my mother that I would one day read the entire epic, in Sanskrit, and thus be able to challenge my grandmother when she would, invariably, quote it wrong. I couldn’t wait to squash her ‘can’t-eat-what-she-touches-because-she-belongs-to-a-lower-caste-family’ and ‘daughters-need-to-be-demure-because-the-gods-created-us-that-way’ mindset.

As the years passed, I returned to and abandoned my promise (to myself) of reading the English translation of the Bhagavad Gita countless times. I’d start reading, intent on finishing, but it would either be too heavy and thus kind of morbid or I wouldn’t understand the point a verse was trying to make and I’d put it aside. It wasn’t well until my 30s that I actually picked up the Bhagavad Gita and stuck to it.

The first time I simply read the verses. The second time I delved deeper, trying to understand the message of each verse and its applicability in daily life. I don’t remember how many times I’ve read it thereafter. Now, I dig into it randomly, choosing to read a few pages every now and then. I like the Penguin editions (and there are many) because they are reader friendly. Recently, I also got a copy of the ‘Saral Gita’ by the Gitapress—this is the Nepali version.

I primarily read the Bhagavad Gita because I wanted to be knowledgeable enough to contest ideas, especially when people got all gung ho in the name of God. “That’s not what’s said in the Bhagavad Gita,” I wanted to be able to say. However, having read it quite a few times now, that need has been sidelined. I’ve started to like what I learn from it. Every time I pick it up, it inspires a new idea, a new thought.

Earlier everything was either black or white for me, but now I realize nothing is that obvious. The Bhagavad Gita does not prescribe one particular path or solution for life. What you take away from each of the 700 verses is entirely up to you. The wisdom of the Gita isn’t only for the devout seeking to guarantee a place for themselves in heaven (which is actually what a close friend seems to think I’m doing). It’s for those of us who are trying to change, be a little better every day, but desperately need help in doing that.

I still hope I’m able to impress (or offend) people with my knowledge of the Bhagavad Gita someday. But I would like to think I’m now wise and mellow enough to not be upset if that never happens.

Of desires and dreams: A book review

No garment is perhaps as controversial as the headscarf. Many women choose to wear it—it signifies who they are and what their culture means to them. In an interview, Pakistani writer Sabyn Javeri said that women wear the hijab for different reasons—some to be able to move around freely, without scrutiny, and others to assert religious identity. There are also women who actually feel sheltered by the headscarf. But a large part of the society sees it as a patriarchal conditioning of women.

_20201013111335.jpg)

It is this idea of the headscarf and what it stands for—which is unique to each woman—that Javeri explores in her collection of short stories, ‘Hijabistan’. The 16 short stories also delve into what it means to be a woman—more specifically a Muslim woman searching for identity—and the hijab is used as a metaphor. Set across Pakistan and London, the stories aren’t only about a piece of clothing. They are about the desires and dreams of women in different circumstances and of what they are capable of doing.

‘The Adulteress’ is about a woman torn between her sense of duty and desires. ‘Under the Flyover’ is about a married couple sneaking in some private moments before heading home to their crowded flat. In ‘The Hijab and Her’, a Pakistani exchange student in America gets picked on by her professor during a discussion on post-colonialism which leads to her choosing a different path in life. In another story, a British Muslim girl is on her way to Syria, contemplating the jihad.

Some stories are also about the struggles an immigrant faces while trying to fit in and staying true to one’s roots. For instance, in ‘The Good Wife’ the protagonist tries to assert her identity by wearing a hijab and ‘Only in London’ is about reinvention of the self by not dressing as the Muslim religion mandates.

Javeri’s prose is smooth and her writing empathetic. None of the stories feel unnecessarily drawn out or pretentious. You will be able to relate with the many characters in the anthology whose age range from 13 to 50. Some stories might feel a little off but you are never bored or disappointed.

Rather, these are stories that make you think—about women who have kept quiet for far too long and all the sacrifices they are forced to make, for their families, in the name of religion, and simply because they are women.

Hijabistan is Javeri’s second book. Her first, ‘Nobody Killed Her’, published in 2017, was a fictionalized tale of a female prime minister’s assassination.

Short Stories

Hijabistan

Sabyn Javeri

Published: 2019

Publisher: Harper Collins

Language: English

Pages: 216, Paperback