Politics in remaking

The national and provincial elections are around the corner for which candidates are in their last leg of campaigning to woo the voters. As in the past, voters are being promised all sorts of things. This is neither unusual, nor are they doing it for the first time. Such promises are common in a country like Nepal where the society has been dependent on politics for everything for a long time. Interesting as it may be, what is true, however, is that most of the candidates have just become dream merchants. Despite all this fanfare on the part of candidates and political parties, people at large look less enthusiastic about the election. The overall national mode is not jubilant. This certainly will have consequences in the electoral outcomes as well. The frustration is all pervasive and deeply running across various sections of society, and is already being manifested. The electoral campaign of major political parties and their leaders have been challenged in the form of the ‘No Not Again’ social media campaign. People’s resentment at old established political parties could reflect in the form of low voter turnout. Or, their frustration could impact the performance of traditional political parties. What led to such a state of affairs? Why is there a deep level of frustration towards electoral politics? Part of the reason is that Nepali politics, over the years, has been hijacked by the parties to fulfill their vested interests and that of their close supporters. True, political leaders and parties have contributed to bring about political changes in the country. But they expect to be rewarded. It does not stop here, there are some leaders who equate their political success with national success and their failure as nations failure. Similarly, frequent formation of (un)holy alliances—Gathabandhan—either to stay in power or to come into power has only reduced people’s trust—often referred to as Janata—in democracy. From that perspective, Gathbandhan is merely a Thagbandhan—a coalition of thugs. Many people who have been closely observing these events are ready to challenge this status quo. If that materializes, this certainly is going to have a deep impact for the traditional political parties, who have been running the show in the country for nearly thirty plus years. During these thirty plus years, there has been a steady rise of the middle class. But it is this group and their children who will likely shape the outcomes of this election. If not, they will at least set a course for future elections. This group is not affiliated to any political parties, and they are not easily be influenced by rhetoric. Political parties are without true agendas this time and the people can see this. Perhaps, they might still be under the impression that their dreams and promises can still be sold in the market. But things have changed. Of course, political parties of various colors and ideologies have come out with their own manifestos with a long list of promises and programs. However, some of them do not truly make any sense to the people, as they are not really connected with their livelihood. Besides, the parties had made similar commitments in the past. If we juxtapose the roundabouts of events, it appears that political parties, at large, are running out of their bank balance of public trust. Under these circumstances, mere ranting and projecting repeated artificial crises in democracy, constitution and sovereignty will not win them public trust. A politician’s career crisis in no way endangers democracy, constitution or national sovereignty. For all practical purposes, the extant election is being contested between two forces: those who are affiliated with political parties in one way or the other, and those who are outside of the party mechanism from every aspect. The latter want to unseat the former at any cost. In that process, independent candidates have come as a blessing in disguise, though independent candidates, too, are not independent in a real sense of the term. For now, they certainly are becoming successful in delivering a message to the traditional political parties and their leaders. Traditional political parties are facing a litmus test. Let us see how they fare this election. Recycling of the same people for more than thirty plus years in politics has brought a deep anti-incumbency wave even within the pirates. Perhaps their young leaders, too, are seeking genuine change. Established political forces must reinvent themselves and change their way of politics if they are to survive and remain relevant.

Leadership blues

As the country heads towards the elections on Nov 20, one could ponder about the emergence of leadership from these electoral contests. A general understanding is that the same crop of old leaders will make it in the fray. But if one is to look at the source from which a new breed of leadership is to emerge, then an interesting picture comes into play. Unlike in the past when the party affiliated youth or student bodies produced future leaders, this time around (possibly starting a decade or so) a different bunch of leaders are making it to the leadership lineup. One of the segments of these leaders is those that are now in the leadership position of the local bodies. The other segment constitutes those that may be termed as technocrats. The likelihood of the emergence of these two segments as possible leaders of party politics in near future is a telling story of the changing political, economic and cultural dynamics of party politics in Nepal. In the recent past, including during the partyless Panchayat period, both youth, student and other sister organizations of the political parties played a strong role to propagate the ideology of their respective parties. In fact, during the Panchayat period these allied institutions served as the front organizations for the then banned parties. The present day second tier leadership of these parties actually comes from these very fraternal organizations. The story of these organizations in the last decade or so is, however, one of sorry state. Ever since the political parties were seated firmly in the control of the state affairs following the declaration of republic, the mother parties started treating their fraternal organization with contempt. The senior party leadership increasingly sought to erode inner- party democracy and their first casualties were these allied organizations. The once vibrant fraternal organization slowly fell into decay to the extent that the leadership for these organizations is no longer elected rather than nominated by the senior leadership of the party. Leader/businessperson In the preceding section, the article demonstrated how the traditional route for the party leadership has weakened. As a result we see a new set of leaders emerging for future leadership. These are people who have won the local elections. These leaders may have come from the aforementioned fraternal organizations of their respective parties. But that is not a very important marker. What really counts is the fact that the person concerned not only enjoys a popular base (not necessarily in the positive sense of the term) but is also financially independent. The elected member of the local body may be a local businessperson or a contractor. Therefore, a new crop of leaders are in the making who are themselves patrons and don’t rely on the business community for resources. This marks an important departure in the leadership race. The present crop of leadership of parties’ fraternal organizations doesn’t necessarily have the same leverage as their compatriots leading the local bodies. Additionally, those elected to local bodies also act as an important life line for the parties when it comes to securing resources. Hence, they generate their own network, which when scaled up can be used at national level as well. Further, it is these elected members in the local bodies with whom the public will identify the parties as they encounter these leaders on an everyday basis. Technocrat as policy leader The other segment of the potential leadership comes from people with technocratic/bureaucratic expertise. These individuals necessarily don’t have to come from the rank and file of the parties, unlike in the past. The history of the political parties suggest that a section of the party leaders themselves acquired training as technocrats and then served as policy experts to their parties. The picture is somewhat different this time around. You now have a group of experts who have not risen in the party as cadre, but have made it to the top by showing their credentials as experts with considerable experience in international/intergovernmental organizations. These individuals have very little ownership in the party concerned as they have no or minuscule experience with the party governance and its working systems. Also, these leaders ‘parachute’ to the center and influence various tiers of the government. In fact, they become the sought after pundits as they also receive the backing of international institutions/centers running both political and financial global systems. In the end The preceding sections have shown how a new leadership is likely to emerge in the Nepali party system. If these are any indications to go by, then a segment of the aspiring leaders who are patronized by the top party leadership will find it difficult to compete with the aforementioned two sections of potential leaders. The former is neither financially autonomous nor has enough technical expertise to prove their mettle. The days after the elections could point to interesting directions from the perspective of future leadership.

ApEx Explainer: Everything you need to know before Nov 20 polls

The local level election held on May 13 was the second of its kind after Nepal adopted federalism. It elected representatives in six metropolitan cities, 11 sub-metropolitan cities, 276 municipalities, and 460 rural municipalities. On Nov 20, the country will once again head to voting stations to elect representatives to the federal parliament and seven provincial assemblies. The polls, which will elect 825 representatives in the federal parliament and provincial assemblies, are being held in a single phase. Here is an explainer on the elections.

How is the federal parliament formed?

The House of Representatives (lower house) and the National Assembly (upper house) make up the federal parliament. The lower house has 275 seats of which, 60 percent (165 seats) are chosen through first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system, while the remaining 40 percent (110 seats) will be elected through a proportional representation (PR) basis. The PR system aims to ensure representation of women, Dalits, Madhesis, indigenous groups, and minorities in the governing structures. Article 85 of the constitution says: “Unless dissolved earlier, the term of the HoR shall be of five years.”

The previous federal and provincial elections took place in two phases in November and December 2017. So, this December will be the end of the five-year term of parliament. The constitution has not envisioned a parliamentary vacuum of over six months; hence it was necessary to conduct parliamentary elections within six months of December 2022. But Nepal didn’t enter this period, as the government announced the elections before December.

However, the Nov 20 election is not for the National Assembly (NA) or the upper house. The NA is a 59-member permanent body, with 56 members chosen by an electoral college consisting of provincial assembly members and village and municipal executive members. The president nominates three members. It has a term of six years, with one-third of its members retiring every two years on a rotational basis.

What about provincial assemblies?

Provincial assemblies are unicameral legislative bodies. The numbers of provincial lawmakers vary from one province to another. Unless dissolved earlier according to the constitution, the term of these assemblies is five years. Their term may be extended for a period not exceeding one year in cases where a proclamation or order of the state of emergency is in effect. As provincial assembly elections were held simultaneously with the federal elections in 2017, the end of their tenure was also in December 2022. Under the FPTP component, twice as many members are elected to provincial assemblies as are elected to the HoR. And just like the lower house of federal parliament, 60 percent of provincial assembly seats are filled through the FPTP system and 40 percent through PR basis.

Province 1 has 93 seats, Madhes has 107, Bagmati has 110, and Gandaki has 60 seats in their respective assemblies. Similarly, Lumbini Province has 87 seats, Karnali has 40, and Sudurpaschim has 53 seats. Altogether, there are 550 seats in the seven provincial assemblies.

What is the role of the Election Commission?

The Election Commission is a constitutional body responsible for conducting and monitoring elections, as well as registering parties and candidates and reporting election outcomes. However, it cannot announce dates for any election. Only the government holds this right. For a long time, the commission has been making a case for its right to do so. According to former commission officials, giving the commission such a mandate will ensure timely elections. As the government has the right to announce dates, the ruling parties often tend to declare elections at their convenience.

Is there any change in our electoral system?

Even though there was a debate about changing the electoral system, Nepal is still following the same election system: a mixed voting system based on FPTP and PR. Ruling coalition partner CPN (Maoist Center) had proposed a completely proportional election system, citing that elections are becoming costly and adopting a fully PR electoral system was a solution. Other parties like the Nepali Congress and CPN-UML did not accept the proposition. A party has to cross the election threshold of three percent of the overall valid vote to be allocated a seat under the PR method. And to be a national party, a party should have at least one seat from FPTP and one from PR in the lower house.

Who can vote?

Those Nepalis who are 18 years old and are registered on the voters’ list of the poll body can vote. As soon as the government announced the election, the Election Commission stopped the voter registration process. And if you didn’t register before the cut-off time, you missed the voting rights this time. The next voter registration process will resume soon after the upcoming elections ends.  If you are a registered voter, you can vote by showing your Voter ID or other government-issued IDs at your respective polling station. Newly registered voters can collect their Voter IDs from the polling centers.

If you are a registered voter, you can vote by showing your Voter ID or other government-issued IDs at your respective polling station. Newly registered voters can collect their Voter IDs from the polling centers.

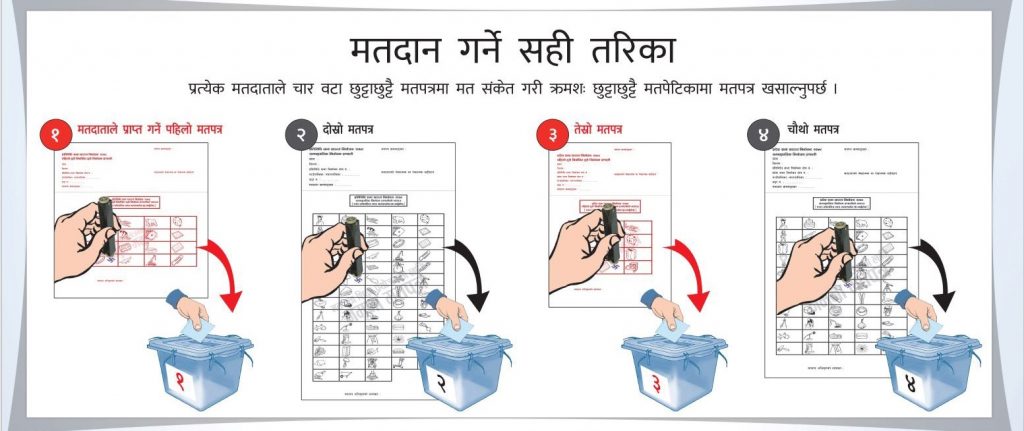

How many types of ballot papers are there this time?

Each voter has to vote on four separate ballot papers this time. There are two ballots (FPTP and PR) for the HoR and two (FPTP and PR) for the Provincial Assembly. For the FPTP election system of the HoR and the PA, the ballot paper has the election symbol and other details printed in red on a white background. While in the PR election system, the ballot paper has black color printed on a white background.  Remember, under the FPTP system, you are directly voting for a candidate of your constituency. Under the PR system, you are voting for a party and the party, if it passes the stipulated threshold, will send as many PR candidates as the seats it won to parliament. The parties have already submitted their PR list to the commission and they will be called up in an already-fixed serial order. There will be four separate ballot boxes as well. Each voter will first get the FPTP ballot paper for the HoR election. After casting the vote in the respective ballot box, the voter will get a PR ballot paper. The same pattern will follow for the provincial assembly.

Remember, under the FPTP system, you are directly voting for a candidate of your constituency. Under the PR system, you are voting for a party and the party, if it passes the stipulated threshold, will send as many PR candidates as the seats it won to parliament. The parties have already submitted their PR list to the commission and they will be called up in an already-fixed serial order. There will be four separate ballot boxes as well. Each voter will first get the FPTP ballot paper for the HoR election. After casting the vote in the respective ballot box, the voter will get a PR ballot paper. The same pattern will follow for the provincial assembly.

How to reduce invalid votes?

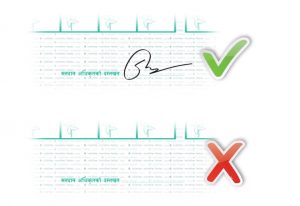

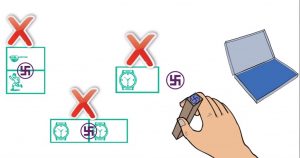

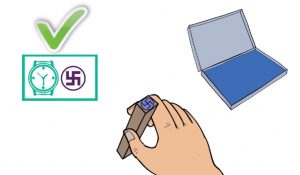

There are a few things you need to do to make your votes count. When you get your ballot paper, check if it has the signature of the voting officer. Use the ‘Swastik’ stamp, which is available in your polling booth, to mark your ballot paper. And make sure to stamp it clearly. Don’t use more or less ink and just stamp it once.

You should only stamp a single electoral symbol on each ballot paper to make your vote valid. Do not cast a vote for multiple symbols. You can neither divide your vote for two symbols. Make sure that your stamp is inside the set box. Do not put your stamp outside the box. It must not overlap with another, horizontally or vertically to make the vote valid. The last part is folding your ballot paper, which is where many people fail. Fold it in a way that the ink does not get smudged or leave an imprint on any other symbol. Be mindful of where the ink stamp is and where it can leave an imprint. It is also a good idea to make sure that the ink has dried before you fold the paper.

You also need to maintain the secrecy of your vote. Do not fold the ballot paper in a way the face of the paper is turned outside. Visit the social media of the Election Commission for a better video graphical explanation of how to make your vote valid.

Why is there no electronic voting machine?

According to Chief Election Commissioner Dinesh Thapaliya, the commission had no problem using the electronic voting machine (EVM), but there was no political consensus regarding its use. The Election Commission had held talks with the leaders of several political parties several times to introduce EVMs, but to no avail.

Could Nepalis outside Nepal vote?

In 2018, the Supreme Court issued a directive to the government, parliament, and the Election Commission to make necessary arrangements to ensure voting rights for all Nepalis living abroad. But this order has been ignored. None of the stakeholders have any valid reason as to why this is. Even though the Maoist Center and the Nepali Congress had said that they would make it possible for Nepalis living abroad to vote, there have not been any positive results. The Election Commission officials say that the parties lack consensus on the matter. Election experts also suggest that political commitment, necessary laws, and resources are a must for this provision. So Nepalis based abroad cannot vote in this election.

What will the country get after the polls?

Same as now, a multi-party, federal democratic republic and parliamentary form of government will be formed after the election. As soon as the members of parliament are elected, it will elect a prime minister, who is the executive head. The leader of the party that wins a simple majority is invited to form the government. The prime minister will then form a cabinet. Similarly, the members of the provincial assemblies will choose chief ministers to run the respective provincial governments. As for the president and vice president, they are constitutional posts with nominal power. An electoral college formed by the two houses of federal parliament and Provincial Assembly members will elect them.

How will people with disabilities vote?

The federal and provincial elections are just days away. Preparations are in full swing. The excitement is palpable, with election-related discussions at every home and tea shop. But for people with disabilities, it’s a tricky situation. Without disabled-friendly infrastructure and facilities, they will have to face many hurdles to cast their votes. Some have chosen not to vote, fearing the humiliation they will have to face at the polling when they can’t fill out the ballot papers or reach the ballot box. The inability to exercise a fundamental right, as guaranteed by the Constitution of Nepal 2015, is infuriating, says Gajendra Budathoki, journalist and editor of Taksar News. Budathoki is wheelchair-bound and has been, over the years, raising his voice to make elections more disabled-friendly. He laments nothing has been done to make the elections inclusive and accessible to all. “The government and the Election Commission could do more if they wanted to. But they don’t. This is nothing new,” he says. Budathoki recalls the 2017 local elections when supporters of a certain party took him to the polling station, almost a kilometer away from his home in Kapan, but they were nowhere to be found once he had voted. The road wasn’t in a good condition and it was quite steep too. Budathoki had a difficult time getting himself home. This time around as well, various parties’ cadres have approached him, promising to facilitate the voting process but he is wary. He will have to figure out how to work around the issues or simply stay at home. Article 42 of the constitution states that people with disabilities shall have the right to participate in state matters on the basis of the principle of inclusion. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2017 states those with disabilities have the right to be candidates as well as cast votes fearlessly and voluntarily, with or without help. Despite these protections in place, people with disabilities are marginalized and hence not granted the equal rights they have been promised. “It’s appalling that the Election Commission takes so much money to prepare for the elections but cites lack of budget where disabled-friendly facilities are concerned,” says Budathoki. Ultimately, the government and the political parties are at fault, he adds. They are blatantly disregarding the law by not including the disabled population in state affairs. Budathoki feels the government doesn’t include issues of people with disability in its discussions with the commission, which in turn gets an excuse not to act. The Election Commission, however, maintains they have done a lot to make the elections as inclusive and disabled-friendly as possible. Shaligram Sharma Poudel, spokesperson for the commission, says the local authorities have been instructed to look into this and to facilitate the process, including making ramps, rope-markings, as well as running awareness programs for volunteers on how to handle people with disabilities. “We will give vehicle passes to people with disabilities so that they can get to the voting station easily. They can also bring someone to help them,” says Poudel. But people with disabilities aren’t assured. Those ApEx spoke to say these are just superficial provisions to mask the EC’s lack of efforts to include voters with disabilities in the upcoming elections. Only 100 out of the 22,000 polling stations have some sort of disabled-friendly infrastructure. These too have been set up with the help of the National Federation of the Disabled, Nepal (NFDN) and the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES). The commission says the 100 polling booths have been set up as models for future elections. The commission seems to have a ‘something is better than nothing’ approach to inclusiveness. The EC doesn’t have any data on the number of voters with disabilities. Electoral materials too haven’t been readied in required formats such as audio, Braille, sign language, and easy-to-read. However, the commission still insists it has worked on making the election inclusive. Surya Prasad Arya, information officer, EC, says they are determined to abide by the constitution and even have a separate budget to make polls disabled-friendly. In July, the commission informed IFES that 100 booths wouldn’t be enough and sought additional help from them. There was no response, he says. But people with disabilities wonder why the government looks for outside assistance without doing the bare minimum itself. What is the election budget spent on when the commission seeks help from the private sector for most of its needs, muses Budathoki. Kiran Shilpakar, chairperson of the National Association of Physical Disabled-Nepal, says people with disabilities are denied their rights time and again on different pretexts. The elections are no different. Be it a tight budget or not enough time to plan, the election body has only excuses to offer. As a once in a five-year event, claiming to be pressed for time shows a lack of empathy, he says. From registering to vote to voting, everything is an ordeal without disabled-friendly infrastructure, say people with disabilities. Journalist Budathoki recalls a harrowing incident when he went to get himself registered on the voter’s list. “There was no accessible way for me to reach the office in my wheelchair. I had to be carried like a sack of potatoes. It was embarrassing,” he says. Then there’s also the issue of whether the commission can ensure fair elections when a section of the population is sidelined. Budathoki says various political parties try to convince people with disabilities to vote for them by playing on their emotions. It’s not uncommon for parties to assign workers to take people with disabilities to voting centers. This can result in the misuse of votes especially when someone requires help filling out the ballot papers. It was found that, in the 2017 federal and provincial elections, votes of the visually impaired and those with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities were misused. Shilpakar adds that the government doesn’t want to address the issue as there’s a lot of ground to cover. People will have different kinds of needs according to the nature of their disability. Some have mobility troubles, some can’t see or hear, while others have intellectual limitations, he says. As a signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities-2006, Nepal can’t remain indifferent to their issues, he adds. Moreover, election is a state event and every citizen has the right to vote. Not making it accessible for people with disabilities is a violation of their basic human rights. Rama Dhakal, vice-president of NFDN, says they have always urged the election body to make voting easy for the disabled. There has to be a lot more public-private partnership to ensure those with disabilities aren’t excluded by the state simply for the lack of infrastructure. The 100 polling stations that NFDN has worked on in collaboration with the IFES are by no means enough but the initiative could be a start of making future elections inclusive, she says. “I take this as a milestone but more work needs to be done,” adds Dhakal.