Nepal struggles to get Covid-19 test kits, protective gear

It has been over four months since the first outbreak of the novel coronavirus was reported in Wuhan of Hubei province, China. On January 24 Nepal recorded its first Covid-19 case. Any way you look at it, Nepal had sufficient time to prepare, including on the purchase of medicines and medical kits. Yet most of this precious time was wasted.

Medical doctors, nurses, and other frontline health workers say they are desperately short on gloves, medical masks, respirators, goggles, face shields, gowns, and aprons. Other urgent needs are ventilators, testing kits, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), and medicines. The testing process has been painfully slow due to the lack of sufficient test kits and other supporting equipment.

Nepal has fallen far short of testing all corona suspects, which is vital to curtailing the spread of the virus. Right now only those who came to Nepal from abroad after the second week of March are being tested. Public health experts say low testing levels could be a reason behind the paucity of detected cases in Nepal, even when compared to other South Asian countries. Similarly, due to the lack of PPE, doctors and other health workers are reluctant to treat those suspected of corona or any other infectious disease.

A doctor at the Kathmandu Medical College (KMC) says that the hospital staff has been told to prepare for the testing and treatment of possible Covid-19 patients, even as they are short on PPE and other protective gear. “Doctors, nurses and other working staffs worry they will be asked to tend to suspected Covid-19 patients even without these protective gears,” the doctor says, requesting anonymity.

The situation is worse outside Kathmandu. For example, in the vulnerable Province 2, there are just 11 ventilators and testing level is slow. Various local governments have also complained of insufficient test kits.

Long and short of it

Dr. Lochan Karki, President of Nepal Medical Association (NMC), acknowledges a slight improvement in the delivery of PPE. “In the initial days, the situation was dire. Things now are better, but we still don’t have sufficient stock if the number of coronavirus cases shoots up,” Karki says. He says still both private and government hospitals are short of vital medical equipment. Some private hospitals are thus trying to get supplies from private companies abroad.

A rising global demand and severe disruptions in global PPE supply chains maybe a reason for the delay in their import in Nepal. But the federal government’s mishandling of the purchasing process is undoubtedly more responsible. First, the government initiated the process too late. Second, the decision to allow a private company to make these imports without due process invited controversy. The contract was scrapped and another one started, which also took time.

To fast track the process, a government-to-government (G2G) purchase was initiated. On March 29, the cabinet instructed Nepal Army to do so. The army wrote to China, India, Israel, Singapore and South Korea, requesting for the needed medical supplies.

The army took nearly three weeks to complete paperwork. Even after this, Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali had to talk to high-level Indian and Chinese officials to hurry things up. Of the five countries, there has been some progress on the purchase of test kits and medical equipment from China, while some medicines have also been imported from India.

Nepal Army completed paperwork to purchase kits and medicine from China on April 20, and the army says it will take another two weeks for the first consignment to arrive. Chinese companies have informed that they are under pressure to deliver to other countries as well. In total, the army will be importing 340 tons of medical supplies worth some Rs 2.24 billion from China—and in multiple stages. The first consignment will be via a charter flight and the subsequent ones will be imported via road.

Wait and watch, not

On the purchase of medicines from India, there has been no substantial progress. Nepal Army has dispatched a list of medicines and equipment but is yet to receive specific prices for those items, says army Spokesperson Bigyan Dev Pandey. India is itself purchasing medical supplies, including test kits, from China. Government officials have not shared details about the progress in bringing medical supplies from Israel, Singapore, and South Korea.

Despite the initial controversy, private companies are also being used for the imports. The Department of Health Services has signed three separate agreements with Om Surgical, Hamro Medi Concern, and Lumbini Health Care for the import of medical goods. These companies are expected to bring medical equipment worth Rs 300 million from China within next two weeks. They could yet take some time to arrive.

As the World Health Organization puts it, the disruptions in the global supply of PPE and other medical supplies owes to, “…rising demand, panic buying and to some extent misuse of those equipment. Supplies can take months to deliver and market manipulation is widespread, with stocks frequently sold to the highest bidder.”

To meet rising global demand, says WHO, the medical industry needs to crack up manufacturing by 40 percent.

Nepal must increase its imports amid all these challenges. Its lethargic health bureaucracy needs to step up its game if Nepal is to tide over the corona crisis with limited damage.

Split of Nepali political parties made easier

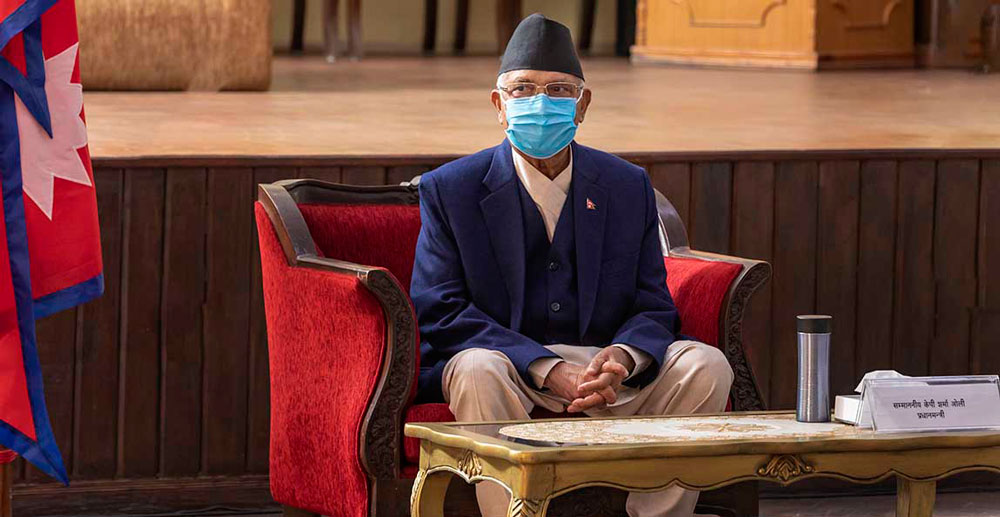

At a time Nepal is struggling with Covid-19, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli-led government on April 20 introduced an ordinance to relax the provision of party split. The ordinance has changed some provisions of the Political Parties Act.

According to new provisions, a new party can be registered at the Election Commission with 40 percent support either in parliamentary party or in party central committee. President Bidya Devi Bhandari issued the ordinance on the cabinet’s recommendation. Earlier, there was the provision of 40 percent support both in parliamentary party as well as the central committee for party split.

The ordinance came at a time when there is news of growing rift inside the ruling Nepal Communist Party. The NCP leaders, however, say the change won’t affect the dynamics of ruling parties.

It is unclear why government amended the law at a time the country is concentrating its efforts on fighting the coronavirus. The provision, however, makes it easy for rival factions of ruling parties to break off.

There are speculations the new ordinance is aimed at engineering a divide among Madhes-based parties. It is rumored that some members of the two main Madhesi parties—the Samajbadi Party and the Rastriya Janata Party Nepal—want to join the government.

Samajbadi leader Upendra Yadav and RJPN’s Rajendra Mahato both said that although the new ordinance was apparently brought to weaken them, the move could backfire on the ruling parties.

Oli’s decision invited criticism from his own and opposition parties. In the cabinet meeting, ministers from former Maoist party objected to the PM’s proposal. Similarly, Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali also opposed it. PM Oli, however, insisted on the proposal’s passage saying that it would not affect NCP dynamics. The main opposition Nepali Congress, in its preliminary reaction, termed the timing of the move ‘inappropriate’.

Nepal’s corona response hobbled with adjourned parliament

As the federal government stumbles in its efforts to manage the Covid-19 crisis and limit its fallout, the need for the scrutiny and oversight of the national parliament is being acutely felt.

The delay in purchase of kits and logistics to fight Covid-19, the issue of people stranded in different parts of the country, the plight of Nepali migrant workers, PM KP Sharma Oli’s reported instruction to ministers and party leaders to stay away from the media, and the controversial recall and restoration of Doctor Sher Bahadur Pun from Sukraraj Hospital—are some issues that could have been credibly discussed and sorted out by an in-session parliament. Similarly, there are reports of local governments politicizing relief packages, and people in need not getting them.

“If the parliament had been sitting, it could have forced the government to address those issues without delay,” says political analyst Shyam Shrestha. It may be difficult to hold a full session of parliament due to the fear of the virus, Shrestha adds, but speakers, committee presidents and lawmakers can still play a more proactive role through videoconferences and other means. “But they seem blissfully unaware of the parliament’s crucial role in the current pandemic.”

After the imposition of the nationwide lockdown, the government had ended the parliament’s winter session. In the parliament’s absence, the only way the government can formulate urgent laws are via ordinances, a temporary measure rarely used in parliamentary democracies. Senior Advocate at Supreme Court and National Assembly member Radheshyam Adhikari thus urges the government and political parties to summon the federal parliament at the earliest. The parliamentary procedures allow the government to call a special session of parliament during a crisis.

“We can convene the parliament after adopting sanitary measures such as washing hands before attending meetings, disinfecting the meeting hall, and barring lawmakers who show virus symptoms,” he says.

No time to hibernate

The government shortened the parliament’s winter session even though there was no legal or constitutional obligation to do so. The 275 members of the House of Representatives and the 59 in the National Assembly are effectively on a break.

Different countries have different ways of running their parliaments during a crisis. The Inter-Parliamentary Union, a global think-thank on Parliament, offers some suggestions.

Only the parliament committees may meet; or the parliament can meet virtually using remote methods. “Many countries are changing their laws to allow the virtual functioning of parliament with a view that lockdown could be extended for long,” the union says.

In Nepal, some parliamentary committees as well as the upper house did try to meet virtually but such meetings were ineffective. Adhikari of the federal upper house says the problem is lack of sophisticated technology to keep the participants engaged. “There is thus no option to physical meetings,” he adds.

Lawmakers suggest convening parliamentary committees of House of Representative, National Assembly and Provincial Assemblies to take up pandemic-related issues. If the cabinet can meet, why can’t parliamentary committees, they ask?

Another Nepali Congress federal upper house lawmaker Prakash Pantha also thinks there should have been more effort to keep the parliament open and functional.

During the pandemic, the government needs to pass emergency bills to allow government to exercise additional powers. In the absence of the parliament, the government is free to introduce ordinances or decrees, which, often, instead of addressing underlying problems, only end up serving vested interests.

Sufficient budget and resources are needed to fight the pandemic. If the current pandemic budget is insufficient, budget needs to be transferred from other heads. For instance, the federal government wants to use the money allocated under constituency development fund, but in the parliament’s absence, it has been unable to do so.

Missing collective wisdom

“During a time of crisis, there is a tendency to justify a centralized leadership. Yet that does not mean the executive cannot make mistakes and does not need check and balance,” says Shrestha, the political analyst. “There is a need for collective wisdom right now, and it is not just about criticizing the government but also supporting its genuine efforts.”

Another important role of the parliament is to hold government accountable. Ruling Nepal Communist Party federal lower house lawmaker Birodh Khatiwada says the parliament can play an important role in monitoring government response to Covid-19. “Discussions are underway on making the parliament functional. If it cannot sit, the parliamentarians can at least monitor the work of the federal, provincial and local governments in their respective constituencies,” Khatiwada says.

Former Prime Minister and Chairman of Federal Council of Socialist Party Baburam Bhattarai, another lower house MP, is also taking the initiative to hold virtual meetings of parliamentary committees. The meeting of the Finance Committee he is a part of was scheduled for April 19, but was put off at the eleventh hour. Expressing his displeasure over the decision to cancel the meeting, Bhattarai tweeted, “Speaker, Committee chair and all concerned were positive on the virtual meeting. If there are legal issues to hold such meetings they should be resolved.”

As per constitutional provisions, the government will have to table its budget in the parliament by May-end. Before that, the president will present government policies and programs. The parties are yet to discuss the kind of constitutional crisis that will ensue if the parliament cannot meet for the budget session. Substantive anti-Covid-19 measures are apparently planned for the budget session. Yet the parliament could not be convened too soon.

The corona impact on Nepal

The novel coronavirus pandemic could have a lasting impact on the functioning of the Nepali state. First, there is now a risk that the government of KP Oli could clamp down on dissent and cement its hold on power on the excuse of tackling Covid-19. Even within the ruling Nepal Communist Party, co-chair Oli could use the pandemic to push back the party’s general convention slated for the second week of April 2021. Or that at least is the fear of party co-chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal camp. Without the general convention, Dahal cannot stake his claim on the party’s sole chairmanship.

Yet there are also those who believe that if PM Oli cannot properly handle the corona crisis, and if he is seen intent on clinging to power by hook or by crook, the tide in the party could turn against Oli. Says NCP leader Deepak Prakash Bhatta: “If PM Oli tries to cover up his weaknesses instead of correcting them, it will lead to growing polarization within the party, with the eventual weakening of incumbent leadership.” Likewise, with political activism around the country coming to a standstill, incumbent Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba could also try to delay the party’s general convention.

Another interesting issue the pandemic has thrown up is the role of the Nepal Army. The national charter allows army mobilization during national emergencies. But even though the pandemic has the country under its grips, the federal government is yet to declare a state of emergency. So how might the army be used? One way would be for the national force to follow the leadership of the Health Ministry, the lead agency in the country’s anti-corona efforts. In fact, even here, there is a big grey area.

This is partly because the National Security Council that can recommend army mobilization to the President has not met in a long time. The NSC could have met at this time of national crisis and charted out a role for the army, which hasn’t happened. Instead, the army has been given the controversial responsibility of importing vital medical equipment, when there was no need to involve the army. “The army could have told the government that it does not want to be involved in such business deals,” says Bhatta, who is also an expert on national security.

There is before us the herculean task of defeating the novel coronavirus that has challenged even the best healthcare systems in the world. This task is made harder still without a clear roadmap, and given the unclear roles of vital state institutions like the Nepal Army and the Armed Police Force. Without working out who is responsible for what and without ensuring a semblance of check and balance, the corona crisis could turn into a catastrophe.

The corona impact on Nepal

The novel coronavirus pandemic could have a lasting impact on the functioning of the Nepali state. First, there is now a risk that the government of KP Oli could clamp down on dissent and cement its hold on power on the excuse of tackling Covid-19. Even within the ruling Nepal Communist Party, co-chair Oli could use the pandemic to push back the party’s general convention slated for the second week of April 2021. Or that at least is the fear of party co-chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal camp. Without the general convention, Dahal cannot stake his claim on the party’s sole chairmanship.

Yet there are also those who believe that if PM Oli cannot properly handle the corona crisis, and if he is seen intent on clinging to power by hook or by crook, the tide in the party could turn against Oli. Says NCP leader Deepak Prakash Bhatta: “If PM Oli tries to cover up his weaknesses instead of correcting them, it will lead to growing polarization within the party, with the eventual weakening of incumbent leadership.” Likewise, with political activism around the country coming to a standstill, incumbent Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba could also try to delay the party’s general convention.

Another interesting issue the pandemic has thrown up is the role of the Nepal Army. The national charter allows army mobilization during national emergencies. But even though the pandemic has the country under its grips, the federal government is yet to declare a state of emergency. So how might the army be used? One way would be for the national force to follow the leadership of the Health Ministry, the lead agency in the country’s anti-corona efforts. In fact, even here, there is a big grey area.

This is partly because the National Security Council that can recommend army mobilization to the President has not met in a long time. The NSC could have met at this time of national crisis and charted out a role for the army, which hasn’t happened. Instead, the army has been given the controversial responsibility of importing vital medical equipment, when there was no need to involve the army. “The army could have told the government that it does not want to be involved in such business deals,” says Bhatta, who is also an expert on national security.

There is before us the herculean task of defeating the novel coronavirus that has challenged even the best healthcare systems in the world. This task is made harder still without a clear roadmap, and given the unclear roles of vital state institutions like the Nepal Army and the Armed Police Force. Without working out who is responsible for what and without ensuring a semblance of check and balance, the corona crisis could turn into a catastrophe.

Covid-19 cases in Nepal climb to 30

Kathmandu: The number of the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) cases in Nepal has reached 30, with 14 new cases reported in the past 24 hours.

According to Ministry of Health and Population, 12 news cases were reported in a mosque in Udayapur district, and two cases in Chitwan district. The ministry has not disclosed the details of people infected. This is most number of cases reported in a single day in Nepal.

In recent days, the government has expedited testing of suspected people and deployed rapid medical test teams in almost all of the 77 districts.

Nepal’s apex court wants safe passage for stranded people

The Supreme Court of Nepal on April 17, Friday issued an interim order to the government to make arrangements for the safe passage of people stranded in various parts of the country. Currently, hundreds of people are taking long and risky journeys to reach their homes from Kathmandu.

Responding to a petition registered by Advocate Prakash Mani Sharma, a joint bench of Justice Ananda Kumar Bhattarai and Sapana Pradhan Malla ordered the federal government to arrange transport of those people. In the protracted lockdown, hundred of people who are mainly employed in unorganized sectors are leaving Kathmandu, as they can’t sustain their livelihood in the capital city.

As per the court order, the government must arrange free meals and transport for them. Due to the travel restrictions imposed by various districts, many are stranded on district borders. The SC also instructed the government not to create hurdles for the people who want to return home.

Though local governments claim they have arranged meals for the poor, but those affected say the relief is insufficient. Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli has already initiated discussions with ministers to arrange transport for the stranded people.

Role of Nepal Army in the pandemic

In democratic countries, the prospect of the national army coming out on the streets makes people nervous. So does its involvement in any business, even in the import of vital kits and equipment to deal with a potentially deadly pandemic.

Article 267 of the Constitution of Nepal 2015 says the role of Nepal Army is to safeguard the country’s independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity, and national unity. Additionally, Article 267(4) says, “The Government of Nepal may also mobilize the Nepal Army in other works including development, construction and disaster management works, as provided for in the federal law.”

Further, “The President shall, on recommendation of the National Security Council and pursuant to a decision of the Government of Nepal, Council of Ministers, declare the mobilization of the Nepal Army in cases where a grave emergency arises in regard to the sovereignty or territorial integrity of Nepal or the security of any part thereof, by war, external aggression, armed rebellion or extreme economic disarray.” A declaration of the mobilization of the Nepal Army must be ratified by the parliament within a month.

Yet there is nothing in the constitution about the role of the national force in the kind of government-to-government procurement of Covid-19 kits that has recently landed it in controversy. “The army could have told the government that it does not want to be involved in such business deals,” says military expert Deepak Prakash Bhatta, who is also a leader of the ruling Nepal Communist Party.

The national army has already taken up several development projects, including Kathmandu-Tarai fast track. Similarly, army personnel have been deployed in disaster management works. In a recent example, the Nepal Army built 869 houses in Bara and Parsa districts that had been ravaged by a tornado in March last year. During floods and landslides, too, army personnel are in the frontline of rescue and rehabilitation works.

Experimental stage

But the army has had no experience of dealing with a pandemic. Security experts say the government can mobilize the national army to deal with the Covid-19 pandemic, but only if its role can be clearly defined within constitutional limits. In other countries, too, the national armies have been mobilized to assist the civilian government. For example, the US government instructed its army to build hospitals. In Spain, it was out in force enforcing the national lockdown.

“Army personnel can, for instance, be mobilized to regulate the Nepal-India border and check the movement of people during the pandemic, which is not happening,” says Bhatta. “After the lockdown, hundreds of Nepali workers have been coming home from India. But they have not been screened properly.” Instead, Minister for Home Affairs Ram Bahadur Thapa has instructed the Armed Police Force (AFP) to monitor the movement of people at the border; the deployment has been inadequate.

Compared to other civil organizations, the national army has a well-trained, more disciplined, and better equipped force. As army’s resources are always oriented to a large-scale war, they can be immediately mobilized to build makeshift hospitals. They have helicopters and vehicles, and bases across the country. If the doctors at government and private hospitals are unwilling to work, the army can mobilize its troops and medical personnel for medical care as well.

The medical services of the Nepal Army had started in 1925 with the establishment of Tri-Chandra Military Hospital at Mahankal, Kathmandu. Renamed Shree Birendra Hospital (SBH) and relocated to Chhauni, it is now a 635-bed sophisticated hospital with a military rehabilitation center, two field hospitals, and 15 field ambulance companies.

Foggy path

The Nepal Army is already involved in controlling the spread of the coronavirus. It has developed a smartphone app for smooth flow of corona-related information. Similarly, the Covid-19 Crisis Management Center has been established in the army barracks in Chhauni. According to security analyst Binoj Basnyat, formation of this center under the Minister of Defense is a signal from Nepal government that the army’s participation is inevitable. “It is the National Security Council that should decide how the Nepal Army is to be deployed,” he says.

But as the NSC has not met for a long time, the role of the Nepal Army in the current corona pandemic remains unclear.

Former Major General of the Nepal Army Tara Bahadur Karki says the NSC should be meeting regularly during a crisis of this magnitude. In the current health emergency, Karki argues, it is the Ministry of Health that should be in the frontline fighting it, with the army playing a backup role. “On the other hand, if the pandemic tomorrow poses a direct threat to the country’s security, then the army has to lead from the front,” he says.

Currently, there are some other mechanisms that can decide on limited deployment of army personnel. The district administration offices can deploy the army at the district level for disaster management, after obtaining permission from the Army Headquarters. At the national level, the Home Ministry can activate the Disaster Relief Act of 2020, clearing the road for the army’s deployment in disaster-control.

“For Covid-19, the army may act as a strategic reserve with heavy medical practitioners and necessary components at the center, operational reserve in the provinces, and fully-involved contribution in the districts,” Basnyat suggests.

One such example army deployment was during the 1918 influenza pandemic in the US, which lasted for 10 months. In the three-phase pandemic, the second phase was the most dangerous, and the US army had to be deployed to control it. “Nepal is now entering the second phase. We should draw the right lessons from history and from the experiences of other countries,” he suggests.