Dilmaya Sunar obituary: The singer who found peace only in death

Birth: 19 Nov 1992, Surkhet

Death: 25 June 2022, Kathmandu

Dilmaya Sunar, a budding Dohori (Nepali traditional folk music genre) singer, died aged 30 on June 25.

Born the second child of the three daughters to her parents, Sunar spent her childhood in a village in Surkhet district tending to the cattle and helping her folks with household chores. She was musically gifted and used to entertain friends with her singing whenever they went to the forest to graze their cattle. But never did Sunar think of being a professional singer.

She was just 13 when her parents married her off against her will. The marriage was full of troubles. Sunar’s husband abused and tortured her no end, but she felt helpless and continued to live with him. The couple had a son and it was upon Sunar to look after the family. She ran a small grocery shop and what little money she made, her husband, a serial gambler, spent most of it.

When Sunar’s family fell into debt due to her husband’s gambling problem, it once again fell on her to settle the loans. She went to Kuwait to work and made enough money to clear the debt as well as build a house in Nepalgunj.

When Sunar returned home after two years, she had hoped her husband would have cleaned up his act by the time. He hadn’t and the couple started falling out again.

Sunar filed for a divorce in 2016 and got herself out of the abusive marriage. Her son chose to stay with his father. She would later find out that her ex-husband had remarried and that he had been abusing her son.

Distraught, Sunar wanted to reunite with her son, but that never happened. Her relationship with her own parents was also failing on the account of her being a divorcee. Once again, she decided to work abroad—only this time, to find her independence.

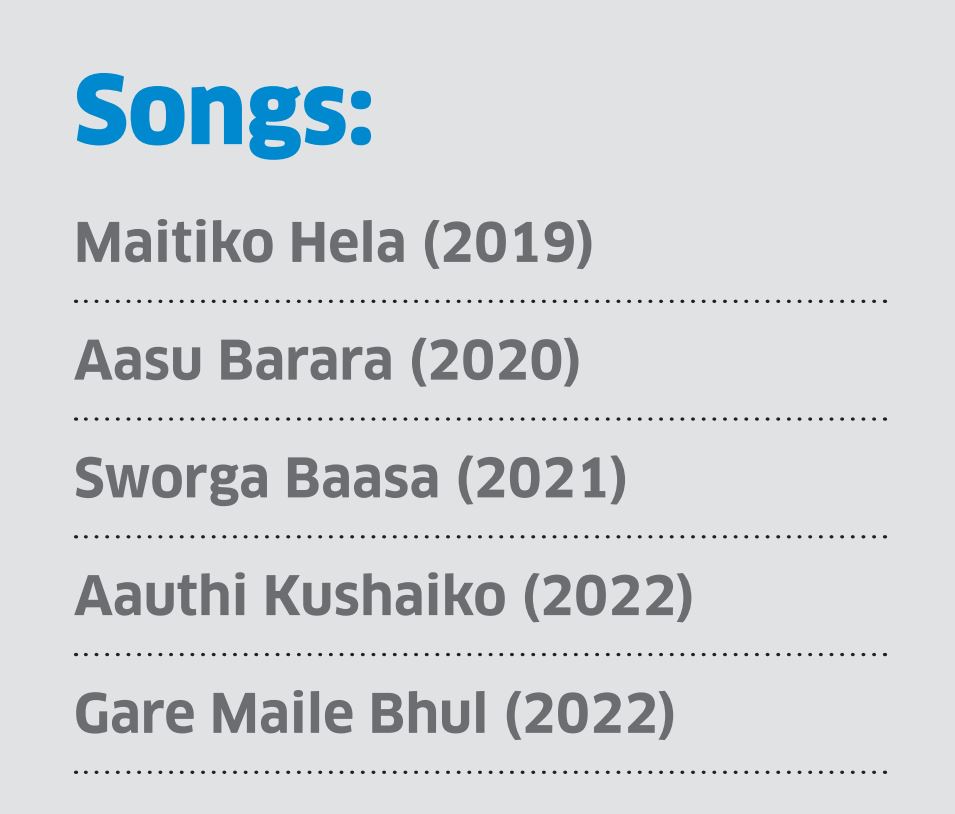

Sunar worked in Oman for a year and returned to Kathmandu in 2018. She rekindled her childhood passion for singing when—encouraged by her neighbors—she began performing at Dohori restaurants and shows. Sunar began pursuing a musical career in earnest after recording a few original songs that were loved by her listeners.

She seemed to be doing well in life and even found her love in a man named Khil Bahadur Shrestha.

But trouble and tragedy never quite left Sunar until her death. She was heart-broken when she discovered that Shrestha had lied to her about his earlier marriage.

On June 25, she was found dead in her rented room. Autopsy ruled her death as a suicide-by-hanging.

Sunar had also tried to kill herself following an argument with Shrestha, three months prior to her actual death, police investigation later revealed.

Kajalkali obituary: Sauraha’s lumbering giant

Kajalkali, a safari elephant who gave fun memories to many visitors who came to holiday in Sauraha, Chitwan, succumbed to old age-related maladies on June 26. She was around 60.

Kajalkali was a reason for joy for many people whom she carried on her back and took on safari of Chitwan National Park, but her own life was not a happy one. She was after all a captive elephant, without a herd or even a natural habitat. She led a domesticated life among humans, who dictated what she did and where she went.

Not much is known about Kajalkali’s early life other than that she was born in India and brought to Sauraha in 2017. For an Asian elephant, she was already in her twilight years when she was put to work as a safari elephant.

“Despite her old age and poor health, she was used for jungle safari for three and a half years,” says Babu Ram Lamichhane, senior conservation officer at the National Trust of Nature Conservation (NTNC).

Although Kajalkali was privately owned, the trust monitored her health and well-being. Kajalkali’s previous owner had last year abandoned her when she started showing signs of illness. He had sold her to an Indian buyer even though the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), as well as the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act, 1973, bans elephant trade.

Kajalkali never made it to India. Authorities intercepted the truck that was transporting her to the south and she was returned to Sauraha.

Shri Lal Pariyar, a hotel owner in Sauraha, took Kajalkali in, as her previous owner wanted nothing to do with her. She was given shelter and fed by the hotel, while the NTNC looked after her medical needs.

“Two caregivers were attending to Kajalkali as she had gotten too feeble,” says Lamichhane.

Kajalkali was showing many signs of aging. For instance, she had lost several teeth, which made it difficult for her to chew.

Elephants can lose and regrow their teeth six times at most. After that, they do not grow back, which was the case for Kajalkali, says Lamichhane. “She wasn't eating properly and became emaciated, which resulted in a severe digestive issue," he adds.

Kajalkali was getting weaker by the day and there came a point where she couldn’t even bear her own weight. She collapsed on May 23 and had to be lifted with an excavator.

“Veterinarians administered her with saline drips to nurse her back to health,” says Lamichhane.

Kajalkali recovered but not fully. She collapsed for the second time on May 31 and then again a few days later, and this time never to get up on her feet.

Kajalkali stopped eating entirely; she couldn’t even drink water. People who witnessed her in her last days reported seeing her drawing water with her trunk and putting it in her mouth, but she was unable to swallow. Every now and then, she would move her feet and trunk but other than that there was barely a movement.

Kajalkali died on the afternoon of June 26 and she was buried on the spot where she took her last breath.

Dr Bhampa Rai obituary: A relentless campaigner for refugee repatriation

Dr Bhampa Rai, a leading figure in the Bhutanese refugee repatriation movement, passed away on June 19. He was 72.

Rai was born and raised in the Bara village of Samchi district in southern Bhutan. His ancestors, originally from Nepal, had migrated to Bhutan during the 17th century.

A surgeon by profession, Rai worked for the Bhutanese royal family before tens of thousands of Nepali speaking Bhutanese fled the country in the early 1990s.

Unlike other Nepali-speaking Bhutanese, Rai and his family were not chased out of the country. As a surgeon to the royal family, the Bhutanese government in fact urged him to stay. Rai left as he could not tolerate the government’s persecution of his people. The stateless people, he felt, needed him more than the royal family.

Rai and his family first made their way to West Bengal, India, where they spent a few months with the other refugees. There he met Ram Karki, a Bhutanese human rights activist now based in the Netherlands.

“He was straightforward and selfless and he wasn’t against any group or community, only against the regime that had evicted his people from their homes,” says Karki of Rai.

After the homeless Bhutanese refugees were chased away by the Indian authorities, they came to Nepal and camped along the Mechi River in eastern Nepal. Life became increasingly hard for them. There were crises of food, water and sanitation, and the people started getting sick.

Rai volunteered medical care to the sick, and he continued his practice even after the refugees were moved to the camps run by the UN High Commission for Refugees.

“He had a clinic in Damak from where he used to offer free healthcare to Bhutanese refugees as well as non-refugees,” Karki says. “He used to get hundreds of calls every single day and he helped everyone.”

As a qualified surgeon, there was no shortage of well-paying job offers for Rai. But he declined them and decided to devote his life for the care of his people.

Rai hoped to one day return to Bhutan and led a repatriation movement to find a rightful place for his people in their native land. He didn’t give up even when the majority of refugees opted to migrate to other parts of the world as part of the UN's third country-resettlement program.

Rai's parents as well as his wife died in Nepal as refugees. He had been living alone in his rented flat.

In May this year, Damak Municipality had honored Rai for his tireless service to the refugees as well as to the local community. He was offered free housing, but for him home was always Bhutan.

“On the day he was honored, he had shared with me his wish to live out the last of his days in Bara, Bhutan,” Karki says. “That wish never came true. Now it is upon us to walk on the path he has shown.”

Rai had been suffering from liver and kidney problems for a long time. On June 14, he underwent operations for hernia and piles and later died of complications from the surgery at Noble Hospital in Biratnagar.

Mithila Chaudhary obituary: Champion of the marginalized

Birth: 20 March 1966, Dhanusha, Nepal

Death: 10 June 2022, New Delhi, India

Mithila Chaudhary, a former minister for population and environment, passed away after a long battle with cancer on June 10. She was 56.

Born to an Indian father and a Nepali mother in Madhubani of Bihar, Chaudhary spent her formative years in India. She married Madan Mohan Chaudhary, a lawyer from Saptari district, in 1984.

Besides being a lawyer, Madan Mohan was also a member of the Bishnu Bahadur Manandhar-led Nepal Communist Party (Samyukta). Chaudhary's interest in politics grew following her marriage.

Her home in Saptari used to be the meeting venue for communist leaders and cadres, and she used to listen to them intently. She was deeply inspired by Manandhar and soon joined the party.

In 1987, Chaudhary lobbied for the establishment of the party’s women’s wing, Nepal National Women Federation, in which she served as the Saptari district committee chair. She also led the women’s front during the anti-Panchayat movement, and encouraged many ordinary women to rise up against the party-less system.

In 1990, during the decisive movement against the Panchayat rule, Chaudhary played a pivotal role to rally party members as well as masses after authorities detained several senior party leaders, including her husband. She too was arrested for spearheading anti-government protests, but soon after democracy was restored in the country she was released along with other party leaders.

Chaudhary continued her political activism post-1990. She led the Mahila Mukti Aandolan of 1996 organized for the rights of the marginalized women. She also engaged herself in the party's promotional campaigns and elections.

In 2001, her political career came to a near end when she suffered a major heart attack. But she bounced right back when her leadership was most needed during the Madhes movement of 2007.

Chaudhary once again proved herself an effective leader, for which she was made the party's lawmaker in the second Constituent Assembly under the proportional representation quota. She had gotten an overwhelming support when her party held an internal vote to pick the lawmaker candidate.

In 2017, Chaudhary was appointed the minister for population and environment in the Sher Bahadur Deuba-led coalition government.

During her tenure as a minister, she did a remarkable job in the field of alternative energy and climate change, and represented Nepal with great pride in the international arena, says her son Abhinav.

Nepal became a member of the International Renewable Energy Association during Chaudhary's tenure. She also represented Nepal at the climate change conference, COP23 held in Bonn, Germany where she urged the world leaders to follow the Paris Agreement.

Chaudhary’s party NCP (Samyukta) merged with the CPN (Maoist Center) while she was in the government. Her engagement in the party affairs started waning following the merger. Meanwhile, her health condition also deteriorated after she was diagnosed with cancer.

Chaudhary parted ways with party politics, but tried to keep herself active to push the cause of the marginalized communities.

Her son Abhinav says she would push him to help the Dalit community that was affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns.

Chaudhary passed away in the course of treatment. She is survived by her husband and their son.