The events that shaped South Asia in 2021

January

The Supreme Court of Pakistan orders the Pakistani government to rebuild a Hindu temple—the Shri Paramhans Ji Maharaj Samadhi temple in Teri, Karak District. The temple was earlier destroyed by a mob of 1,500 local Muslims led by a local Islamic cleric and supporters of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam party in December 2020. As a part of renovation, the temple plans to expand and the houses nearby will have to be razed, irking many locals and Islamists.

February

India and China agree to push for a mutually acceptable resolution of friction points at Gogra, Hot Springs and Depsang along the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh in a steady and orderly manner. However, in subsequent months, there is little progress on border talks between the two countries.

March

On March 26 and 27, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visits Bangladesh at the invitation of his counterpart Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, and takes part in two gala celebrations—the golden jubilee of the independence of Bangladesh and the birth centenary of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the iconic leader of Bangladesh’s freedom struggle and the country’s first prime minister. Protests erupt across the country, with protestors accusing Modi of committing crimes against humanity during the 2002 Gujarat riots. They slam his anti-Muslim policies and India’s interference in Bangladeshi politics.

April

The United States decides to withdraw US and NATO troops from Afghanistan, stating that “there is no military solution to the challenges Afghanistan faces”. Then Afghan President Ashraf Ghani welcomes the decision.

May

X-Press Pearl, a Singaporean container ship, catches fire off the Sri Lankan coast of Colombo, and was engulfed in flames on May 27. The Criminal Investigations Department of Sri Lanka arrests the ship captain in June after the incident draws global attention due its harm to the local biodiversity.

June

Foreign Minister Abdulla Shahid of the Maldives is elected new president of the United Nations General Assembly. Shahid pledges to push for equal access for coronavirus vaccines, a stronger and greener economic recovery and stepped-up efforts to tackle climate change.

July

Acclaimed Indian photojournalist and Pulitzer Prize winner Danish Siddiqui is killed by the Taliban in Afghanistan on 13 July 2021. He was embedded with a convoy of Afghan security forces and covering a clash between the security forces and the Taliban near a border crossing with Pakistan.

August

Taliban returns to power in Afghanistan after two decades. Amid the chaos, incumbent Afghan President Ashraf Ghani escapes the country on August 15. America withdraws all its troops, to worldwide condemnation of its ‘hasty’ decision.

September

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and US President Joe Biden hold their first in-person meeting during Modi’s US visit. Two leaders discuss trade, security and other regional issues. In 2021, India and the US come closer on many issues in the backdrop of souring India-China relations.

October

A mob damages 66 houses and sets on fire at least 20 homes of Hindus in Bangladesh over an alleged blasphemous social media post. This follows protests by the minority community against temple vandalism incidents during Durga Puja celebrations.

In a step towards resolving their boundary disputes, Bhutan and China sign a three-step roadmap to help speed up talks, at a video meeting of their foreign ministers. The roadmap is expected to kick-start progress on boundary talks that have been stalled for five years.

November

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, not known for backing down from his political moves, announces the repeal of three new agricultural reform laws on November 19, on Guru Nanak Jayanti. The repeal forbids the entry of private players in farming which would have cut farmers’ income.

December

India’s Chief of Defense Staff Bipin Rawat, his wife Madhulika Rawat, and 11 others are killed in a Mi-17V5 chopper crash near Coonoor, Nilgiris district, in Tamil Nadu, on December 8. The four-star general is the single-point advisor to the Indian government on military matters.

Amid growing India-China and China-US rivalry, Russian President Vladimir Putin visits India to participate in India-Russia Summit. The two countries agree to enhance bilateral ties.

The events that shaped Nepal in 2021

January

Amid the political chaos that ensured following Prime Minister KP Oli’s decision to dissolve the federal lower house at the end of 2020, four former chief justices—Min Bahadur Rayamajhi, Anup Raj Sharma, Kalyan Shrestha, and Sushila Karki—release a statement on January 8 terming the dissolution unconstitutional. The unprecedented statement by ex-chief justices on a political issue draws mixed reaction.

February

On February 23, the Supreme Court overturns Prime Minister Oli’s Dec 20 house dissolution, calling it unconstitutional, and orders the government to summon the house within the next 13 days.

March

The Supreme Court on March 7, the day the meeting of the restored House is scheduled, revives the CPN-UML and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Center), invalidating the Nepal Communist Party (NCP), the outcome of the two parties’ May 2018 merger.

April

Then main opposition Nepali Congress initiates moves to topple Prime Minister Oli and form an alternative government under its leadership with the support of the CPN-Maoist Center and other parties. The party Central Committee on April 3 decides to form a new government under its leadership.

May

President Bidya Devi Bhandari dissolves the House of Representatives as per Article 76 (7) yet again and declares two-phase elections—November 12 and November 19—on the recommendation of the Council of Ministers. This happens after Prime Minister Oli fails to get a vote of confidence in parliament on May 10.

June

PM Oli expands and reshuffles the cabinet, which now has 14 members from CPN (UML) and 11 from Mahantha Thakur faction of JSPN. The Supreme Court issues an interim order, annulling the cabinet expansion. The order relieves 20 ministers of their positions, with the cabinet now composed of only four ministers.

July

The Supreme Court on July 12 overturns Prime Minister Oli’s May 21 house dissolution and orders the appointment of Sher Bahadur Deuba, Nepali Congress president, as prime minister. The five-member constitutional bench led by Chief Justice Cholendra Shumsher Rana says Oli’s claim to the post of prime minister as per Article 76 (5) is unconstitutional. The SC also orders the government to reconvene the house by July 18.

August

Kul Prasad KC is appointed the chief minister of Lumbini on August 12. On August 18, Ashta Laxmi Shakya is appointed the CM of Bagmati province; there is a fissure in CPN-UML, the largest party in parliament, with the formation of the breakaway CPN (Unified Socialist) under former Prime Minister Madhav Kumar Nepal; and the JSPN splits to form LSP led by Mahantha Thakur. The outcome is that there are now six national parties.

September

The Sher Bahadur Deuba government replaces the KP Oli government’s budget ordinance with a fresh bill on September 10. Finance Minister Janardan Sharma presents a budget of Rs 1.632 trillion, reducing the size by Rs 16.74 billion.

October

Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba leaves for London, UK for the COP26 summit, on October 29. Nepal Bar Association and SC justices protest, seeking the resignation of CJ Cholendra Shamsher JBR following rumors of his involvement in cabinet expansion.

November

CPN-UML convenes its 10th general convention and re-elects KP Sharma Oli as party chairman, who handsomely defeats Bhim Rawal, his nearest rival for the post.

December

Nepali Congress holds its 14th general convention. Prime Minister and incumbent party president Sher Bahadur Deuba is re-elected party president. Rastriya Prajatantra Party holds its general convention where Rajendra Lingden beats Kamal Thapa for the party’s top post.

2021: A year of politicization of democracy

A year of political turmoil and ‘politicization of democracy’, 2021 witnessed political parties and their custodians exploit democracy to weaken its basic tenets. Then-Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli dissolved the House of Representatives twice and each time defended his unconstitutional decision, saying fresh elections would buttress Nepali democracy.

Opposition parties dubbed Oli’s move “regressive” yet they too tried to influence the judiciary from the streets in the name of defending democracy. In fact, in 2021, all major political forces tried to use democracy to serve their personal or party interests.

Political analysts thus reckon there was an extreme politicization of democracy in 2021. PM Oli dissolved Parliament on 20 December 2020, and its repercussions were evident throughout 2021. The Supreme Court (SC) invalidated Oli’s move but that didn’t deter him from dissolving the House, again, in May 2021.

Political analyst Chandra Dev Bhatta says 2021 was “the year of politicization of democracy” as power-struggles among political leaders manifested in such a way that they started blaming each other for undermining democracy.

Each labeled the other ‘a threat to democracy’ and went to the extent of splitting their own party, says Bhatta. “In reality, they were only trying to hide their weaknesses.” Not only that, they went a step further and dragged the country’s neighbors into their mess, again all in the name of protecting democracy, adds Bhatta.

The year also saw a hollowing of democratic institutions. For instance, the Election Commission, an independent constitutional body mandated to hold elections and regulate political parties, was hamstrung due to political pressure.

The commission could not take a timely decision on the split of Nepal Communist Party owing to the due influence of political parties, an issue that was later settled in court. This clearly demonstrated compromising of the autonomy of constitutional bodies like the EC, undercutting their credibility.

Appointments in constitutional bodies sans parliamentary hearings came under national and international scrutiny. Appointments in the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), for instance, drew national and international criticism and there were concerns about its independence. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, in an unprecedented move, even sought clarification from the commission over its autonomy and independence.

Also read: Will Deuba ditch the coalition for MCC?

Similarly, questions were raised over the appointment process and autonomy of other constitutional bodies.

Moreover, Nepal’s judiciary faced an unprecedented crisis this year. Probably for the first time in the country’s judicial history, SC judges launched a revolt against a sitting Chief Justice, bringing the judicial process to a grinding halt. CJ Cholendra Shumsher Rana was accused of trading court verdicts for political appointments. Similarly, there were accusations of corruption against other judges.

“The judiciary is the guardian of democracy. But then Nepal’s judiciary is in crisis, which means its democracy is also imperiled,” says advocate and another political analyst Dinesh Tripathi. He adds that the judiciary is on the verge of a collapse, and bad governance characterizes all state institutions.

The nexus between politicians and judges also deepened.

Political parties, on the one hand, tried to influence the judiciary to issue verdicts in their favor through street protests and other propaganda machineries. Supreme Court justices, on the other hand, hobnobbed with the politicians, to bargain for favors in exchange.

Similarly, the Parliament came under increasing executive pressure. The Parliament was dissolved twice, only to be revived each time by the judiciary’s help.

In another important development, there was a lot of bad blood between then Prime Minister Oli and Speaker Agni Prasad Sapkota. Several times, the government would close House sessions without consulting the speaker. The war of words between PM Oli and the Speaker affected the principle of separation of powers.

Even after the Parliament’s reinstatement, it was never allowed to function smoothly. The main opposition CPN-UML has been disturbing the House, raising questions over the Speaker’s role.

In fact, due to the executive’s constant inference, the Parliament’s role has been severely constrained. Both KP Sharma Oli- and Sher Bahadur Deuba-led governments showed their lack of commitment to parliamentary supremacy, for instance through the issuance of ordinances by skipping the House of Representatives.

Also read: Does Deuba’s victory mean early elections?

Most ordinances were issued to fulfill petty interests such as splitting parties or making political appointments.

Tripathi says there were attempts to cause massive damage to democracy. There were repeated attacks on the Parliament, the temple of democracy. “There were attempts at no less than to dismantle democracy but fortunately, it survived,” says Tripathi.

The office of the president was also dragged into controversy. President Bidya Devi Bhandari was accused of siding with then Prime Minister Oli instead of playing a neutral arbiter.

Along with the backsliding of democracy, the general public’s hopes for political stability—rekindled with the formation of a two-thirds majority government in 2018—were dashed. The window of stability had closed and 2021 had sowed seeds for another bout of political instability.

The powerful Nepal Communist Party (NCP) suffered a three-way split, which now means the chances of a single-party majority government is slim in the near future. NCP missed a historic chance of steering the country on the path of political stability and economic development.

Now, there is a fragile five-party coalition government that could crash any time, plunging the country into uncertainty.

Analyst Bhatta points out that the intra- and inter-party tensions that were the result of the leaders’ unchecked political ambitions have marred Nepali democracy. Over time, everything ended up in court and Nepal’s democracy became a “legal issue” and not a “popular one” based on people’s sovereignty.

If things go as planned, 2022 will see the start of three-tier elections. Timely elections could heal the damages inflicted upon democracy in 2021.

But advocate Tripathi isn’t optimistic as Nepali democracy is already on a shaky ground. “We can say democracy is on the verge of a collapse due to our weak state institutions. Even though the Parliament was reinstated, it is defunct. Moreover, it is no more a place to champion people’s voices and aspirations, which is not a healthy sign for our democracy,” says Tripathi.

This year the major political parties held their General Conventions electing new leaderships yet serious lapses were seen in their practice of internal democracy. Tripathi says almost all parties once again failed to ensure internal democracy, their long-standing vice. “There can be no democracy without internal party democracy,” says Tripathi.

No political party for Nepalis with disabilities

Article 29 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) says, “State parties shall guarantee to persons with disabilities, political and public rights and the opportunity to enjoy them on an equal basis with others.”

Around 15 years after the convention’s drafting, the entire world has lately taken a stand in favor of proportional inclusion and representation for the population with disabilities. Nepal is one of the laggards.

According to the 2011 census, around 1.94 percent of Nepal’s population lives with some form of disability. The preamble of the Constitution of Nepal 2015 talks of building “… an egalitarian society founded on the proportional inclusive and participatory principles to ensure economic equality …” This means, in each sector, two percent of the seats are to be set aside for the persons with disabilities (PWDs).

But have we adhered to the provisions of our constitution and international treaties?

As politics lies at the center of everything, it is worth asking how inclusive this field is when it comes to the PWDs. Not very much, unfortunately.

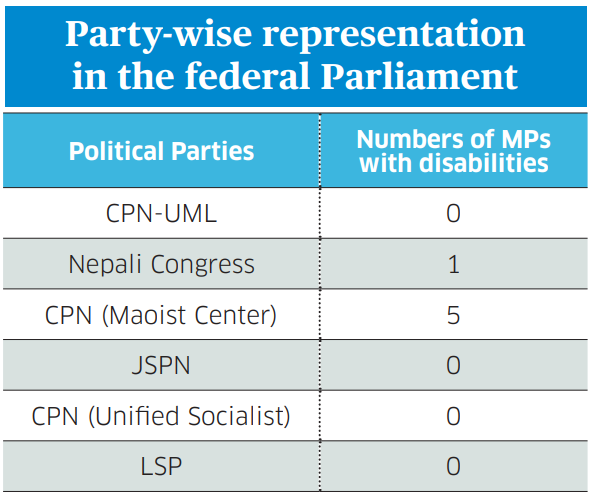

In the federal parliament of Nepal, of 275 MPs, only two are with disabilities, both from the CPN (Maoist Center). The Maoists have thus provided relatively more seats to the people living with disabilities, but they also consider those injured in the armed rebellion as PWDs. Chudamani Khadka, an MP with a disability due to a bullet injury he sustained during the insurgency, is a long-time personal aide to chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal.

Teknath Neupane, former chairman of Apangata Sangathan Nepal, a Maoist PWD sister organization, accepts that the party has given more priority to those who sustained injuries during the conflict over those born with disabilities. Injured cadres from the armed revolution who were ready to sacrifice their lives for the party deserve the attention, he says. But, he adds, “They have now gained enough recognition and time has come to start treating all those with disabilities with the same yardsticks.”

Party spokesperson Narayan Kaji Shrestha accepts that those who got disabilities during the conflict climbed the ladder of political leadership faster compared to other PWDs.

A recent standing committee decision, before the party’s national conference, made it mandatory for party units to select at least one person with disability as a delegate to the convention from each local level. “We are strengthening the party from the base-up and ultimately, each will find his or her rightful place in leadership,” Shrestha promises.

In the National Assembly, there are four PWDs—one from Nepali Congress and three from Maoists. Similarly, the seven provincial parliaments, in total, have no more than a PWDs, all from Congress and Maoists. CPN-UML and other parties don’t have a single such provincial lawmaker.

“There are 15 MPs who qualify as PWDs in the country. This number should have been enough to raise our issues in parliaments, but regretfully, only few of them consider themselves PWDs,” says Bhojraj Shrestha, chairman of Rastriya Loktantrik Apanga Sangh, the Nepali Congress sister wing for the person with disabilities.

Shrestha, along with 22 other members, had formed the organization back in 2006, but the party officially recognized it only in 2009.

Says Jagadish Prasad Adhikari, general secretary of Loktantrik Rastriya Apanga Sangathan, a CPN-UML sister organization, who also was a convention representative at the 10th UML General Convention, “My party has neither addressed our issues nor given us a seat on party committees.”

Also read: Nepal struggling to deal with new refugees

During the latest UML general convention, not a single person with disability won a party-leadership position. Of the 12 PWD delegates, five were from the quota of the sister wings. “We didn’t contest as the party asked us for consensus and we respected the policy, but later, we got scammed,” he says.

Newly elected UML Secretary Yogesh Bhattarai says there was no restriction to contest elections. For him, inclusion is a new concept, and it takes time to adapt. “We are discussing separate seats for the person with disabilities in the party’s committees,” he adds. But UML recently published the nominated list of 30 members in the central committee and again, not a single party person with a disability got the nomination. According to Bhattarai, the party is still working to include them besides the central committee.

As the Maoist national conference is around the corner, cadres of its PWD wing are hopeful of more representation in the party. “Our party has shown the way, it’s time to see how they implement the policies,” says Neupane.

Because of poor management, Nepali Congress hasn’t been able to hold its 16 district conventions, barring many deserving party members from filing candidacies. The same happened with Shrestha of the NC sister wing, as he didn’t get to contest for the posts. “Of the six people with disability who are contesting for a seat in the central committee, almost none consider themselves a PWD or part of the disability movement,” he adds with disappointment. “But I am sure they are the ones who will win.”

Debu Parajuli was told by the Rastriya Prajatantra Party that they have no quota for the PWDs. She then filed her candidacy for central committee member from the open category, getting the sixth most votes.

“People with disabilities can stand toe to toe with anyone,” she says. “Quotas are necessary but if you don’t fit into them, please enter the contest from the open category. That I won means that I defeated an ‘able’ person,” Parajuli says.

The other problem is that political parties’ leaderships still don’t deem the person with disabilities good enough for important party posts. Moreover, the PWD quotas are often misused.

Mitra Lal Sharma

President, National Federation of the Disabled-Nepal (NFDN)

Our presence in decision-making is a must

I find it pathetic when people think that our needs and aspirations should be confined to getting wheelchairs and other disability-friendly infrastructure. We are not given leadership positions even when we have the requisite knowledge and skills.

Let’s compete. This is an open challenge to the leaders of mainstream political parties. If the people/team you carry can defeat us with your knowledge, ideology and skills, we are fine with not being included, but what if we win? They need our vote and tax, but not our knowledge. Let me ask our political leaders: What is the required qualification to lead a major political party?

When there is a lack of our participation in policymaking, the problems of the people with disability can’t be addressed as other people do not know about our issues and even if they do, they often don’t bother to speak about them. So our presence in decision-making is a must.