A ‘populist’ budget

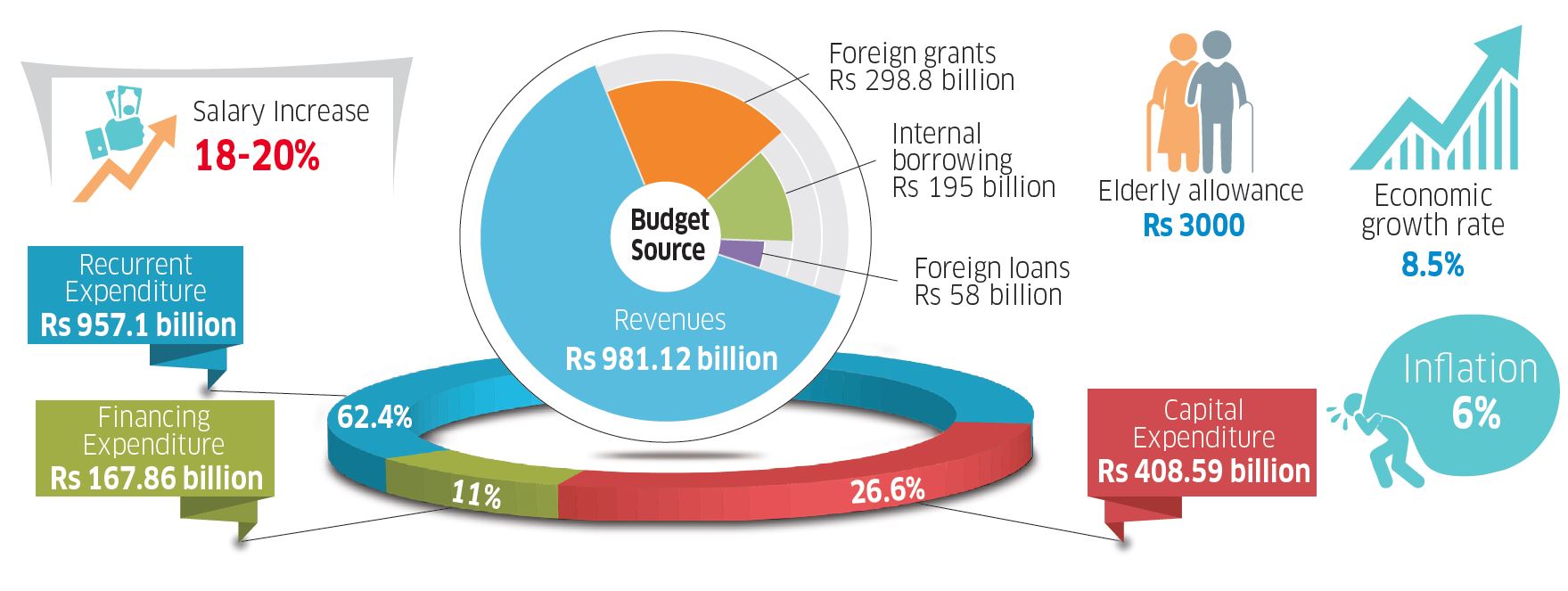

On May 29, Minister of Finance Dr Yubaraj Khatiwada unveiled a budget of Rs 1.53 trillion for the fiscal 2019/2020. The budget, which exceeds the current fiscal’s value by Rs 217 billion, has been termed ‘populist’ by some financial analysts while others have given it the tags of ‘over-ambitious’ and ‘unrealistic.’ Unveiling the fiscal budget in the federal parliament, Minister Khatiwada announced the government’s aim of achieving the ‘middle-income country’ status by 2030 while the economic growth rate for the coming year has been set at 8.5 percent, 1.5 percent more than the current year’s revised target. The targeted inflation is 6 percent.

What have become dearer?

Normally, prices of certain luxury goods increase with the yearly budget and the coming fiscal is no exception. Here’s a list of what will cost you more, and by how much.

| Petrol/Diesel (per liter) | Rs 1.5 |

| Telephone connection rate | Rs 500 |

| Casino royalty | 30 percent |

| Local beer (per liter) | Rs 165 |

| All Whisky/Vodka (per liter) | Rs 920- Rs 1,325 |

| Imported Wine (per liter) | Rs 370- Rs 430 |

| Domestic Wine (per liter) | Rs 135 |

| Brandy (per liter) | Rs 165 |

| Tobacco (per kg) | Rs 95 |

| Chewing tobacco (per kg) | Rs 610 |

| Cement (per ton) | Rs 220 |

| Mobile Phones | 2.5 percent |

| Cigarette (per carton) | Rs 495-Rs 2,715 |

| Juice (per liter) | Rs 11 |

| Pan masala (per kg) | Rs 610 |

| Kurkure/Lays (per kilo) | Rs 17 |

| Betel nut (per kilo) | Rs 225 |

| Energy drinks (per liter) | Rs 30 |

Highlights of the budget 2019/2020

- Rs 60 million for each MP to develop his constituency

- Elderly allowance increases by Rs 1,000, to Rs 3,000 a month

- Civil employees’ salaries raised by up to 20 pc

- Increased the tax threshold on individual income from Rs 350,000 to Rs 400,000

- Rs 130 billion for provincial and local levels

- Over Rs 43 billion allocated for drinking water and hygiene

- Rs 23.6 billion allocated for irrigation programs

- Rs 163 billion appropriated for Railway and Waterways

- Rs 400 million appropriated for ‘improvement’ of Bir Hospital

A lesson from New Zealand

In her address to the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced the need for her government “to address the societal well-being of our nation, not just the economic well-being”. This week, the New Zealand government presented its first “Wellbeing Budget”, a progressive document that has the potential to inspire other countries, including Nepal, which also presented its annual budget this week.

As trailblazing as it was, Ardern and her Finance Minister Grant Robertson took inspiration from different studies and experiences, including works by economists Jospeh E. Stiglitz, Amartya Sen and Jean Paul Fitoussi who, in the middle of the 2008 financial crisis, led a commission to study possible alternatives to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a yardstick to assess people’s economic and social progress.

Ardern asked herself three questions: Is the “Wellbeing Budget” intergenerational, positively impacting future generations? Does it go beyond the narrow definition of success and take into account other aspects of life? Does it bring government agencies to work closer for achieving common goals?

Considered for many years as an economic “rock star” thanks to the previous center-right governments that created successful pathways for businesses to grow and prosper, now the challenge PM Ardern is taking head on is to turn New Zealand into a “rock star” for the well-being of its citizens. While economic indicators have been extremely good for many years, quite a few New Zealanders were falling behind, with youths, especially those from the Maori community and immigrants from South Pacific nations, hit particularly hard. The country also has high rates of homelessness and suicide. In short, many have been left behind despite New Zealand’s overall economic prosperity.

The “Wellbeing Budget” has set five priorities: transitioning to a sustainable economy, improving mental health, boosting innovation, lifting disadvantaged youth, and reducing child poverty. What is interesting is the process that led to the selection of these priorities.

I am talking not just about standard consultations, but a scientific approach based on a Living Standard Framework, with a baseline of around 60 indicators with complex spider graphs able to analyze and project whether selected population groups are likely to experience high levels of well-being. To be honest, it is complex and it not surprising that it has faced criticism.

The LSE, divided into three sections—Our People, Our Country, and Our Future—identifies four capitals (human, social, natural and financial/physical) that must be addressed to meet the aspirations of the citizens of New Zealand.

In a recent pre-budget speech addressing the concerns of the business community, Ardern said that “while economic growth is important—and something we will continue to pursue—it alone does not guarantee improvements to New Zealanders’ living standards”. In another pre-budget speech, Finance Minister Robertson affirmed that “Yes, we need prosperity, but we also need to care about how we sustain and maintain that and who gets to share in it”.

What is striking is not only the powerful moral rationale, but also the idea of bringing together all the ministries to change the status quo and achieve clear outcomes, each related to the five policy priorities. Going beyond a sectoral approach, getting various ministries to work together on multiple interlinked goals is crucial. In New Zealand, they call this “whole-of-government approach” and it means, in Robertson’ s words, “stepping out of the silos of agencies and working together to assess, develop and implement initiatives to improve wellbeing.”

Nepal is in a unique phase. It now has an ambitious constitution that is reinventing the way the government is run. New mechanisms and rules related to the basic functioning of the three tiers of government are being formulated. There is probably the need to identify key policy areas and invest in them strategically.

Many Nepalis die each year in road accidents. No matter how many committees have been set up, the frequency of accidents seems to be increasing. On education, while it is good that the concerned ministry wants model community schools around the country, the overall resources allocated to such a key sector are being trimmed. Important social security schemes have been launched, but implementation is patchy at best and really messy in some cases.

The right to free healthcare is still not guaranteed, with poor implementation of already weak policies that are supposed to provide free services to the neediest. The country was great at reducing the infant mortality rate, but it is failing its citizens in other health areas. (Part of the blame goes to the donors.)

The federal and provincial governments should put ego aside and agree, through talks, on key issues that could truly translate into reality the slogan of “Prosperous Nepal, Happy Nepalis”.

We should not forget that for Robertson, New Zealander’s Finance Minister, “Wellbeing means people living lives of purpose, balance and meaning to them, and having the capabilities to do so”.

Nepal needs an aspirational, while at the same time, realistic budget with well thought out and well-structured initiatives and programs. While identifying major issues to be addressed strategically over the next fiscal year may have been challenging, the bigger challenge will be to muster the consistency and grit to pursue budgetary goals.

The author is Co-Founder of ENGAGE, an NGO partnering with youths living with disabilities.

Entire ward without land ownership certificates

By Parmananda Pandey | Tikapur

Setraj Budha’s family moved to Tikapur in Kailali, a district in the western plains, from the hill district of Achham, in 1964. Many from his village had migrated to Tikapur around the same time. Together, they cleared the forest and have been farming and living in the land ever since. Interestingly, none of them have land ownership certificates.

Bhim Mahar lives and does farming in the same ward. His father Gagan Singh Mahar had migrated there from the hills. He had made the area his home after the District Forest Office, Kanchanpur, back in the mid-60s, gave migrants the go-ahead to “clear forest areas and settle”. Gagan Singh then built a house and raised his children there, but passed away without getting a land certificate.

Around 2,000 hectares of land in Ward 8 of Tikapur is officially not owned by anybody

Settlers in 80 percent of the land in Ward 8 of Tikapur are without a land certificate, even though they have been living there for years. Some have a certificate, but their land cannot be found in official records. Around 2,000 hectares of land in the ward is officially not owned by anybody.

“We made several efforts to solve this problem but to no avail,” says Ammar Bahadur Saud, a local, who does have a land ownership certificate, but his land is not found in official records.

Ward chair Dirgha Thakulla says, “Officials from the survey department have visited us multiple times, and taken measurements thrice, but they are yet to issue certificates.”

Lack of certificates greatly inconveniences the locals. For instance, they do not get subsidies from the agriculture ministry. “We have been unable to split or sell the land that we have had from our grandfather’s time. This has even led to family feuds,” says Sher Bahadur Budha, another local. Tikapur also shares a border with India and disputes over border issues erupt from time to time

‘Land ownership certificates for everyone within the next four years’

By Laxman Pokhrel | Butwal

The federal government has expressed its commitment to provide land ownership certificates within the next four years to all landless squatters living haphazardly in various urban settlements across the country. Minister for Land Management, Cooperatives and Poverty Alleviation Padma Aryal promised that the government would give priority to squatters who own land but do not have certificates to prove ownership, and to those living in unmanaged settlements.

On May 26, 464 land ownership certificates were distributed in Sainamaina municipality

She informed that the government’s drive to distribute land ownership certificates has already started. It began on May 26 from Buddhanagar in Sainamaina municipality in Rupendehi district. On that day, as many as 464 land ownership certificates were distributed. Minister Aryal said the drive would be expanded to other districts as well and reiterated the government’s promise to solve the problem of landless squatters during its tenure.

Eighteen years on

In a meeting with then Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala a few weeks after the royal massacre on 1 June 2001, King Gyanendra had said, and I quote Koirala’s personal aide at the time Puranjan Acharya, “Mr. PM, people see you as a corrupt and unpopular leader.” This made Koirala furious, and he replied, “Your majesty, people also accuse you of stealing idols from temples.” This exchange shows the degree of animosity between King Gyanendra and PM Koirala following the royal massacre. Soon after he came back to the prime minister’s residence in Baluwatar from the palace, Koirala asked Acharya to find out the telephone numbers of some Maoist leaders, with whom he wanted to talk about overthrowing King Gyanendra.

Eighteen years ago, Nepal witnessed a horrible royal massacre, which observers say was the beginning of the end of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic. Many political leaders say the issue of republicanism came as a reaction to the massacre and subsequent political developments rather than as a principled position of the political parties.

For the first time in Nepal’s modern history, the 2001 royal massacre brought the monarchy’s weaknesses to the fore, and created confusion among ordinary citizens. King Gyanendra failed to establish cordial relations not only with PM Koirala but also with other political leaders.

The monarch started consolidating power, taking advantage of the unpopularity of the political parties which had been unable to curb corruption and the Maoist insurgency. The parties, on the other hand, were trying to stop the king from taking absolute power. Many political leaders and observers say it was the royal massacre that planted the seed of republicanism in the minds of the general people.

“If the royal massacre had not taken place, the events of 4 October 2002—when King Gyanendra sacked the democratically elected Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba—and of 1 February 2005—when the king imposed an emergency and took absolute power—could have been averted,” says Kamal Thapa, Chair of the Rastriya Prajatantra Party, who at the time worked closely with the king. “But those steps by the king led the parliamentary parties and the Maoist rebels to sign the 12-point understanding that heralded a republican Nepal.”

A different peace deal?

Even before the massacre, when the Maoist rebels had intensified their violent activities across the country, King Birendra had requested political parties and the government to take the insurgency seriously. A few months before the massacre, King Birendra had sent an informal letter to the government, asking it to resolve the Maoist insurgency as soon as possible. At the same time, some royal family members were holding informal talks with the Maoists about initiating a peace process. Many political leaders say the royal massacre took place at a time when King Birendra was preparing to take decisive steps to resolve the Maoist insurgency.

Soon after the massacre, then second-in-command of the Maoist party, Baburam Bhattarai, wrote an op-ed in the Kantipur daily entitled, ‘Let’s not give legitimacy to the beneficiaries of the new Kot Massacre’, which praised King Birendra for having a liberal political ideology and for being a patriot. In that piece, Bhattarai also wrote of how King Birendra had refused to mobilize the army to suppress the Maoist movement and that various national and international forces were unhappy with his soft approach toward the rebels.

"If the royal massacre had not happened, there could have been a different peace deal"

Kamal Thapa

“If the royal massacre had not happened, there could have been a different peace deal,” says Thapa. The Maoists could have accepted a ‘ceremonial’ or ‘cultural’ king. But following the massacre, the Seven Party Alliance and the Maoists agreed to get rid of the monarchy, which became easier because of Gyanendra’s unpopularity and the support from external forces, particularly India.

Before the royal massacre, discourse on the establishment of republicanism was virtually non-existent. Mainstream political parties used to instruct their cadres not to speak in favor of a republic. Only the Maoist rebels and some fringe communist parties talked about abolishing the monarchy. The massacre laid the groundwork for such a discourse among academics, politicians, media workers and the general public alike.

A large section of the public sees Gyanedra’s hand in the massacre—which is why his acceptability as a king plummeted. Although many Nepalis still have a soft corner for the slain King Birendra, public respect for the monarchy as an institution plunged after the massacre.

Missing debate

“A separate peace deal between the palace and the Maoists was a possibility, but minimizing the role of the parliamentary parties was not,” says Nepali Congress leader Gagan Thapa. “The royal massacre served as a decisive moment for the establishment of republicanism in Nepal, because people did not like the idea of Gyanendra continuing the tradition of monarchy,” says Thapa, who became vocal about a republic soon after the massacre. For this, Thapa was publicly criticized by party President Koirala. “Contrary to general perception, I don’t think the Maoist revolt or the 2006 people’s movement laid the foundation for a republic. Rather it was the 2001 palace massacre that did so. There hasn’t been enough discussion about the impact of the massacre on the establishment of a republic in Nepal.”

Soon after the massacre, an NC team led by senior leader Narahari Acharya launched a nation-wide campaign to swing public opinion in favor of republicanism and federalism. NC President Girija Prasad Koirala had strongly objected to the campaign, saying that it went against the party line.

“We were even barred from making speeches. In a real sense, the royal massacre sparked the debate on republicanism,” recalls NC leader Madhu Acharya, a participant of that campaign. “Had it not been for the massacre, I do not think Nepal would have been a republic today. King Gyanedra committed a series of blunders, which further served to create an environment for a republic,” he adds.

Wither investigation?

Around the massacre’s anniversary, political leaders pledge to launch a proper investigation and make the truth public. Many believe such an investigation remains relevant. Former Speaker Taranath Ranabhat, who was a member of the probe committee formed under the leadership of then Chief Justice Kedar Nath Upadhayay soon after the massacre, says a deeper investigation into the palace carnage is necessary.

His probe committee had concluded that Prince Dipendra had murdered his entire family in an intoxicated stupor, but many doubt its veracity.

“The massacre has had negative social repercussions. It made our country weak. Its long-term impact is even bigger than that of the Maoist revolt,” says Ranabhat. “After the reconstruction of infrastructure, people could gradually forget the insurgency, but the wounds of the royal massacre may never heal. It is never too late to seriously investigate the palace massacre, but subsequent governments have not been serious,” says Ranabhat.

But wasn’t that the job of his probe team? “Our job at the time was to undertake an on-the-spot investigation to determine how exactly the event unfolded. We were not mandated to investigate what caused the massacre,” he adds.

It’s been 18 years since the massacre, but it remains a mystery as to why it happened. The country has undergone massive political changes in these years—changes that the massacre influenced, if only indirectly. Many books have been written on it, yet none has been able to convince the skeptical public. Less in doubt are the momentous repercussions of the massacre on the country’s political course.