What’s up with Nijgadh International Airport?

Nepal witnessed two major air disasters in 1992, prompting the then government led by Girija Prasad Koirala to commission a survey to find an alternative to Kathmandu’s Tribhuvan International Airport (TIA). Of the eight sites proposed by the Nepal Engineering Consultancy Service Center Limited in 1995, Nijgadh was deemed the most suitable. A Korean company conducted a feasibility study in Nijgadh the same year and came up with a cost estimate of Rs 700bn. But things went nowhere for another 13 years.

In 2008, the government led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal revived the idea and decided to undertake the project under the Build Own Operate and Transfer (BOOT) model. Two years later, in March 2010, the Ministry of Civil Aviation signed a $3.55m contract with Landmark Worldwide, a Korean company, to carry out a detailed feasibility study. The company submitted its report to the government on 2 Aug 2011. But the plan stalled, again.

Then, in 2019, the Nepal Investment Board announced a global tender to build the airport. But the board’s attempt to attract foreign investors fell flat without the project’s Detailed Project Report (DPR) and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports.

In its policies and programs, the current government announced a start of airport construction from the fiscal 2023/24. However, there are challenges galore. Over the years, there has been a strong opposition against the airport project, mainly around environment and other viability issues.

After the formation of the KP Oli led-government in 2018, the then Civil Aviation Minister Rabindra Adhikari had made the airport one of his priorities. But when the EIA report came out, the project became a major environmental concern. The report proposed cutting down 2.5m trees to make room for the airport, causing unprecedented damage to local flora and fauna.

Of the 80.45 sq km land allocated for the airport, almost 70 sq km are dense forests. Moreover, the proposed site is three to four times that covered by even the biggest airports in the world.

The latest Supreme Court verdict has directed the government to carry out a fresh EIA of the site and to ensure minimal environmental damage during project-development.

Top leaders of the ruling five-party alliance, including Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba, recently pledged to build the proposed Nijgadh International Airport come what may. They even visited the proposed site. The Nijgadh International Airport project is also important because it is linked to other mega-undertakings like the Kathmandu-Tarai Fast Track and the Outer Ring Road. And yet, over the years, the airport plan has been marred by sluggish progress, increasing costs and a myriad other controversies.

The airport should have minimal environmental impact

Arjun Dhakal

Environmentalist

At issue here are not only environment and wildlife, but also other important things like DPR, EIA, budget, viability, feasibility, etc. In a national pride project, each of these things must be thoroughly studied.

One of the most sensitive but lesser-known issues is that the proposed area, which traverses a water corridor, receives excessive rainfall. Only last week, it got 225mm of rainfall in eight hours.

Even though all the major political parties are in the airport’s favor, none is interested in conducting a detailed study. The Supreme Court has instructed concerned authorities to start from the beginning, and this time, with all the resources and research, the project is likely to go ahead, finally. It is crucial that the airport be built with minimal damage to surrounding areas.

The government should also be clear about the airport’s purpose. What kind of airport are we talking about here? One aimed at handling cargo or passengers? No one knows for sure.

InDepth: Is our energy ecosystem consumer-friendly?

Binod Kumar Bista is a Bachelors of Art (BA) student at Kathmandu’s Ratna Rajyalaxmi College. Originally from a village in Kailali district of far-western Nepal, he lives in a rented room and cooks for himself using LPG. Bista knows the induction stove is more cost-effective and energy-efficient. Yet he is hesitant to make the switch.

“I have limited time for cooking. What if the electricity suddenly goes out?” the 21-year-old asks. “I also cannot afford to have both the options at the same time.”

Research suggests heat-efficiency of induction cookers is nearly 90 percent, while that of conventional gas stoves is 50 percent. The former are also lighter on the consumers’ pockets. A 2021 study conducted by Amrit Man Nakarmi, a professor at the Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University, found that cooking on an induction stove is over 50 percent cheaper than cooking on gas.

Yet Nepalis are reluctant to fully switch to induction cookers. While most urban households rely on LPG for cooking, biomass—at a staggering 67 percent—remains Nepal’s dominant energy source.

What makes people cling to traditional energy sources and is anything being done to change their behavior?

Also read: Possibilities and pitfalls of hydroelectricity

Our energy system doesn’t factor in consumer voice. The authorities dictate whatever they think is right.

At least in the case of biomass and rural electricity distribution, there is more consumer participation in rule-making and enforcement.

Bista’s family in Kailali uses biomass for cooking even though they also have an LPG stove. His family hasn’t fully switched to gas as firewood is both cheaper and more easily available. He says another reason many families in his village prefer firewood to LPG is because they are afraid of possible mishaps from gas-use, while some reckon that food cooked on firewood tastes better.

Dipak Gyawali, former minister of water resources, says it is difficult to get people to move to electricity, but, ultimately, they will have to make the upgrade.

“For example, instead of jumping into electricity from firewood, people in rural areas can start with briquettes or improved cooking. Briquettes are cleaner, forest-friendly, longer burning, and more economical than traditional logs,” he says.

Bharati Pathak, chairman of the Federation of Community Forestry Users Nepal, says while the demand for briquettes and charcoal is high in both urban and rural Nepal, one problem is that the Chinese products have captured the market.

“Many forest products can be used for briquette production. If we could minimize production costs with greater use of technology, the beneficiaries of community forests could benefit a lot financially,” she says.

As for encouraging the LPG-to-electric switch in city areas, the Alternative Energy Promotion Center (APEC) has recently introduced a free induction stove distribution scheme for university students in Kathmandu valley. Almost 13,000 students have applied. An AEPC representative says this scheme will help students adopt induction and change their perception of electric cookers.

Nepal uses most of its energy for cooking and transport purposes. While the use of induction stoves and electric vehicles has been rising, they are still not used in sufficient numbers to achieve energy-efficiency. Many people bought induction stoves when there was a major LPG shortage during the 2015 Indian blockade and at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Similarly, the skyrocketing fuel prices, driven by the Russia-Ukraine war, have persuaded at least some vehicle owners to switch to electric options.

Shrabya Sapkota has been riding a petrol-run scooter for almost five years and is now trying to switch to electric.

“Five rupees of petrol in my scooter gives me a kilometer’s mileage. But if I were to have an electric scooter, I would have to spend just 30 paisa to get the same mileage,” the 22-year-old says. “Say, I do 1,000 km on the road a month. In that case, in three years, I will save around Rs 170,000. Even if I have to replace the e-scooter battery, which costs around Rs 100,000, I still save Rs 70,000.”

But Sapkota represents only a tiny fraction of people who are willing to ditch their fossil fuel-run vehicles for electric ones. There is a general belief that electric vehicles (EVs) are expensive and don’t do well off-road, even though users’ experience suggests otherwise. Consumers are also concerned about the unavailability of charging stations on long-distance travel.

Also read: A snapshot of Nepal’s energy ecosystem

A few electric vehicle companies have opened up charging stations across the country to boost their client numbers—and the approach seems to be working. If other companies follow suit, energy experts expect a significant rise in adoption of EVs.

Brijesh Shrestha, an electric car owner, says humans are by nature resistant to change.

“I too had second thoughts while getting the electric car,” he says. “Many more charging stations and infrastructure should be built to convince folks to go electric.”

The budget for the fiscal 2021/22 had slashed import duties on battery-powered vehicles from 40 percent to 10 percent in a bid to promote their use. Electric vehicles of up to 100kW capacity had to pay 10 percent in custom duties. Likewise, vehicles of 100-200kW capacity paid 15 percent, while 200-300kW vehicles paid 40 percent.

According to the Department of Customs, 1,103 electric cars worth Rs 3.24bn entered Nepal between mid-July to mid-January in the fiscal year. In the same period in the previous fiscal year, only 51 cars valued at Rs 105.19m had been imported.

EV dealers in Nepal see a bright future for electric vehicles: they have been able to meet only 30 percent of demand as India hasn’t been producing enough EVs. But the latest budget has been a dampener.

In its budget for the fiscal year 2022/23, the government significantly hiked excise and customs duties on EVs. A 30 percent customs and 30 percent excise duties have been slapped on EVs of 100-200kW capacity. For electric cars of 201-300kW capacity, customs and excise have been set at 45 percent each. Similarly, excise and custom duties for EVs of over 300kW capacity have been upped to 60 percent each.

This has increased the price of EVs in the Nepali markets, making it difficult for consumers to jump to the electric mode of transport.

Also read: Working out the right combo

Even if people were to move to electric vehicles in droves, there is a lingering concern about the carrying capacity of electricity lines. Nepal’s per capita energy consumption of around 300 units is the lowest in South Asia. This means the country will need a lot of energy in the coming days as it modernizes. Moreover, the current distribution lines are made for lighting purposes, and if people were to switch to electric stoves and vehicles in large numbers, the lines may collapse.

Besides, the consumption of electricity is also growing in rural Nepal.

“The Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) has been unable to provide sufficient electricity in rural areas,” says Mahendra Prasad Chudal, program manager at the National Association of Community Electricity Users-Nepal. “We are trying to sort out a few problems related to bulk-buying and distribution of electricity with the NEA.”

NEA spokesperson Suresh Bahadur Bhattarai says power production is a dynamic process and the agency has been upgrading its system in line with changing demands.

“We have been appealing to the public to switch to electricity. We wouldn’t have done so if our infrastructure couldn’t bear the load,” he says. “To promote electric vehicles, we are also planning to install at least 50 charging stations across the country within the next fiscal year.”

The progressive devaluation of Nepali currency

The exchange of any two currencies is carried out based on two types of rates—pegged rate (fixed exchange rate) and floating rate (converted exchange rate). The currency exchange rate is determined and managed by the central bank of each country. The exchange rate is generally determined based on demand and supply.

The exchange rate of Nepali currency, which is pegged to the Indian currency, has fallen as the Indian currency has been taking one hit after another following the Covid-19 outbreak and the Russia-Ukraine war.

Nepal has an import-based economy, so the devaluation of the domestic currency against the US dollar will also impact the imports of foreign goods.

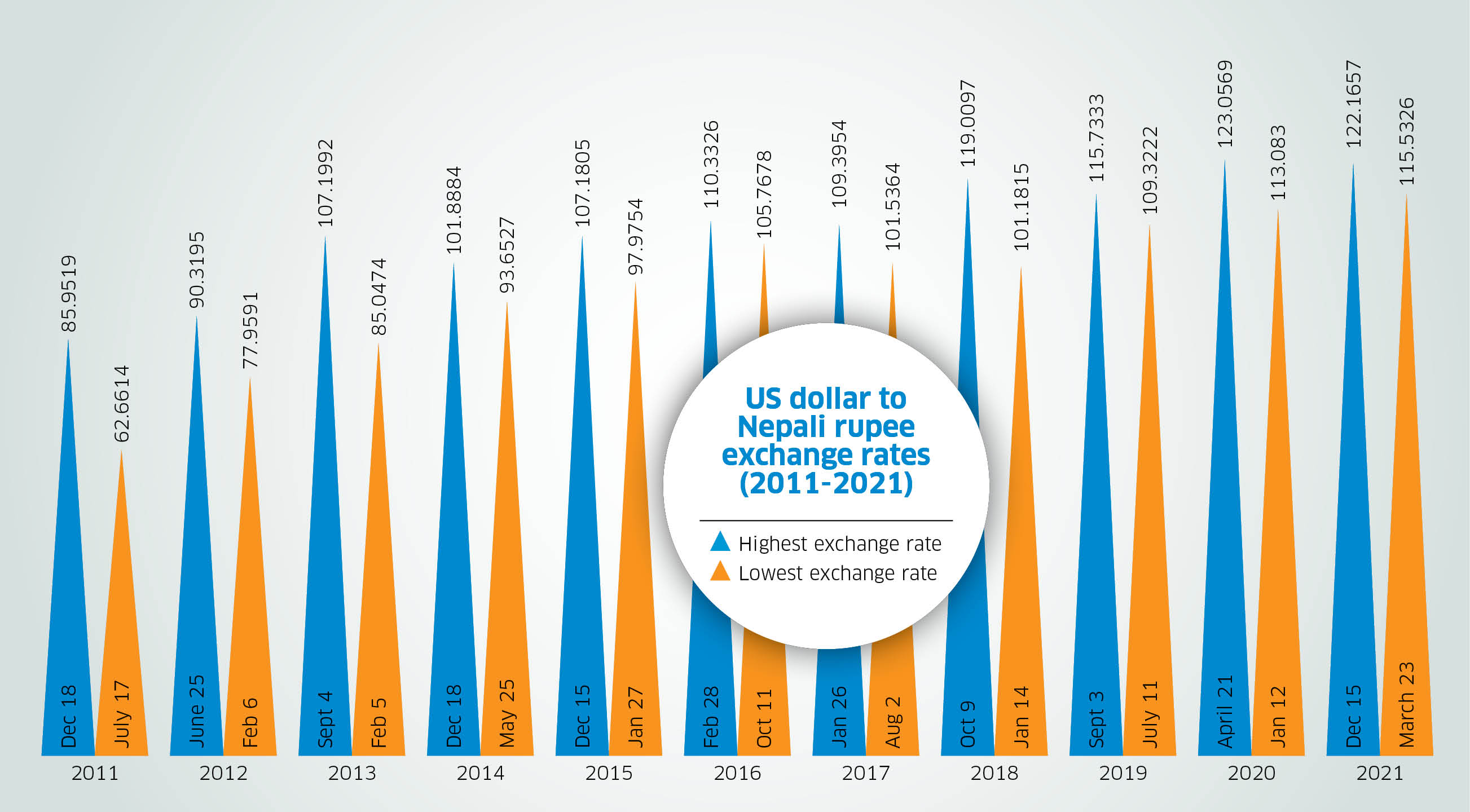

In the past decade, the dollar-Nepali rupee exchange rate has significantly increased. In 2011, the average exchange rate for a dollar was Rs 74. As the Nepali rupee weakened, a dollar fetched Rs 85 in 2012, Rs 93 in 2013, and Rs 97 in 2014.

The downward trend continued in the following years. As of 2022, the highest exchange rate is Rs 125 for a dollar.

If our economy was export-oriented, the dollar’s strengthening could have been an opportunity. But weak currencies make imports expensive and also create inflationary pressures on the economy. Similarly, the country incurs a loss while repaying foreign loans in dollars.

The immediate effect of the devaluation of the Nepali currency is reflected in the expansion of exports and contraction of imports, which tends to negatively impact balance of payments.

We could have benefitted from the appreciation of the dollar as remittances that migrant workers send home would then increase in value. Unfortunately, this is not the case as even remittances have gone down in recent times.

Unpegging would have made us another Sri Lanka

Chiranjibi Nepal

Ex-governor of Nepal Rastra Bank

Our international valuation relies on Indian forex as we have pegged our currency to that of India. The reason behind the depreciation of the Nepali rupee is the fall of the Indian rupee. In 2011, a dollar was equal to IRs 46, so the Nepali rupee was valued at Rs 74. Now, a dollar fetches IRs 77, which takes the valuation of the Nepali rupee to Rs 125. The depreciation rate is the same for both Indian and Nepali currencies.

There is an old question: why can’t we float our currency? This is because the currency is a very sensitive matter. International markets do not recognize our currency because of our poor economy. First, we have to increase our exports to India. Unless our goods can compete in Indian markets, it is impossible to enter the international arena.

Even if we lift our economy, the pegging to the international market should be a slow process. When a former governor of Nepal Rastra Bank had talked about unpegging our currency from the Indian rupee. This led to an acute shortage of Indian currency in Nepal and affected our trade. So unless we are independent in goods, our direct link to the international market should not be an option. If we had pegged ourselves with the dollar, our situation would have been worse than that of Sri Lanka.

The public should trust the currency. Once, because of lack of trust, Cambodian people stopped using their currency and shifted their transactions to the dollar.

Mithila Chaudhary obituary: Champion of the marginalized

Birth: 20 March 1966, Dhanusha, Nepal

Death: 10 June 2022, New Delhi, India

Mithila Chaudhary, a former minister for population and environment, passed away after a long battle with cancer on June 10. She was 56.

Born to an Indian father and a Nepali mother in Madhubani of Bihar, Chaudhary spent her formative years in India. She married Madan Mohan Chaudhary, a lawyer from Saptari district, in 1984.

Besides being a lawyer, Madan Mohan was also a member of the Bishnu Bahadur Manandhar-led Nepal Communist Party (Samyukta). Chaudhary's interest in politics grew following her marriage.

Her home in Saptari used to be the meeting venue for communist leaders and cadres, and she used to listen to them intently. She was deeply inspired by Manandhar and soon joined the party.

In 1987, Chaudhary lobbied for the establishment of the party’s women’s wing, Nepal National Women Federation, in which she served as the Saptari district committee chair. She also led the women’s front during the anti-Panchayat movement, and encouraged many ordinary women to rise up against the party-less system.

In 1990, during the decisive movement against the Panchayat rule, Chaudhary played a pivotal role to rally party members as well as masses after authorities detained several senior party leaders, including her husband. She too was arrested for spearheading anti-government protests, but soon after democracy was restored in the country she was released along with other party leaders.

Chaudhary continued her political activism post-1990. She led the Mahila Mukti Aandolan of 1996 organized for the rights of the marginalized women. She also engaged herself in the party's promotional campaigns and elections.

In 2001, her political career came to a near end when she suffered a major heart attack. But she bounced right back when her leadership was most needed during the Madhes movement of 2007.

Chaudhary once again proved herself an effective leader, for which she was made the party's lawmaker in the second Constituent Assembly under the proportional representation quota. She had gotten an overwhelming support when her party held an internal vote to pick the lawmaker candidate.

In 2017, Chaudhary was appointed the minister for population and environment in the Sher Bahadur Deuba-led coalition government.

During her tenure as a minister, she did a remarkable job in the field of alternative energy and climate change, and represented Nepal with great pride in the international arena, says her son Abhinav.

Nepal became a member of the International Renewable Energy Association during Chaudhary's tenure. She also represented Nepal at the climate change conference, COP23 held in Bonn, Germany where she urged the world leaders to follow the Paris Agreement.

Chaudhary’s party NCP (Samyukta) merged with the CPN (Maoist Center) while she was in the government. Her engagement in the party affairs started waning following the merger. Meanwhile, her health condition also deteriorated after she was diagnosed with cancer.

Chaudhary parted ways with party politics, but tried to keep herself active to push the cause of the marginalized communities.

Her son Abhinav says she would push him to help the Dalit community that was affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns.

Chaudhary passed away in the course of treatment. She is survived by her husband and their son.

InDepth: A snapshot of Nepal’s energy ecosystem

Modern life is unthinkable without energy-power. We need energy to cook food, to get to our offices and even to enjoy our favorite movies. As such, with growing urbanization, Nepal’s energy needs are also increasing.

The country gets its energy from various sources, mainly hydro plants, fossil fuel, sun and biomass.

Hydro plants

The government-owned Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) is the main stakeholder of most hydropower plants in Nepal.

The country has two types of hydropower plants: micro and large. Large-scale hydropower generation started with a 500kW capacity plant in Pharping in 1911. It was followed by two other projects in Sundarijal (1936) and Panauti (1965), respectively.

Eight decades after the start of the first hydropower project, the government introduced the Hydropower Development Policy in 1992, inviting both domestic and foreign private investment. There are now 113 working large-scale hydropower stations in Nepal.

The NEA was formed on 16 Aug 1985 under the Nepal Electricity Authority Act 1984. It came to being following the merger of the Department of Electricity under the Ministry of Water Resources, the Nepal Electricity Corporation, and other related development boards, with the goal of creating a consolidated, one-stop organization.

The NEA’s primary objective is to generate, transmit and distribute adequate, reliable, and affordable power by planning, constructing, operating, and maintaining all generation, transmission, and distribution facilities in Nepal’s power system.

Micro-hydro plants have been installed in Nepal since the 1960s, mainly for agro-processing, with locally developed turbines replacing diesel engines. The Agriculture Development Bank Nepal also started providing loans to village entrepreneurs to set up paddy mills, oil expellers, etc. But until 1980, the focus was primarily on large-scale hydro stations.

In 1981, the government started subsidizing micro-hydro plants, with a subsequent boost in their number. Several turbine mills were fitted with a small dynamo to generate electricity in what were mostly off-grid, isolated plants serving local villages.

Office of Alternative Energy Promotion Center (AEPC) in Mid-baneshwor, Kathmandu | Photo: Pratik Rayamajhi

Office of Alternative Energy Promotion Center (AEPC) in Mid-baneshwor, Kathmandu | Photo: Pratik Rayamajhi

In 2000, the Alternative Energy Promotion Center (AEPC) was formed to look after the 10-100kW micro-hydro power plants. The objective was to generate renewable energy and boost efficiency of energy resources to improve the living conditions of people and combat climate change.

The center also works on the development of commercially viable alternative energy industries. Besides hydropower, it focuses on other renewable energy sources like solar, wind, improved biomass, and biogas.

In 2015, the NEA and the APEC agreed to join the Syaurah Bhumi Micro Hydro Project (23kW) to the national grid. The project came on steam on 11 January 2018, delivering 178,245 units of electricity annually. As of now, there are 17 micro-hydropower power plants in Nepal.

Ajoy Karki, director at Sanima Hydro and Engineering, a hydropower consultant, says micro-hydro projects were all the rage until a decade ago but investors these days prefer larger-scale projects.

“As important and profitable micro-hydro projects are, larger investments in big projects result in bigger profits, too” he says.

Karki is of the view that people in rural Nepal should collectively invest in micro-hydro, and with the help of local governments seek to generate both electricity and capital.

Half a million households from 54 districts across Nepal use community electricity via the Community Rural Electricity Entities (CREEs)—with the National Association of Community Electricity Users-Nepal (NACEUN) as their primary stakeholder.

CREEs buys electricity from NEA in bulk and distributes it to remote consumers. The organization currently has a network of over 300 CREEs.

Vidhyut Utpadan Company Ltd, Rastriya Prasaran Grid Company Ltd, and Hydroelectricity Investment and Development Company Ltd are the other major government stakeholders in Nepal’s hydroelectricity generation.

Petroleum products

The state-monopoly Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC) was established in 1970 to import, store and distribute petroleum products throughout the country.

Nepal depends on import of refined petroleum products from the Indian Oil Corporation (IOC). Besides the NOC, no other public or private entity is allowed to import petroleum products.

The NOC renews its agreement with the IOC every five years for the smooth supply of petroleum products. LPG is imported from privately-owned bottling industries from different parts of India under an NOC product-delivery order.

According to the NOC, Nepal currently consumes 150,000kl of diesel and 60,000kl of petrol a month, with a total burden of Rs 30bn on the exchequer. In recent times, the import of petroleum products–largely consumed by households, motor vehicles and industries–has increased by 15 percent a year.

In the fiscal 2020-21, Nepal’s consumption of petrol, diesel, kerosene, aviation fuel, and LPG was 587,677kl, 1,698,427kl, 23,427kl, 70,400kl and 477,753mt respectively, informs petroleum products expert Chakra Bahadur Khadka. “We must act immediately to reduce this consumption by switching to renewable energies as import of fossil fuels helps neither our foreign reserve nor the environment.”

The corporation incurs a per-liter loss of Rs 24.70 on petrol and Rs 18.01 on diesel used in public transport, industry and projects. In LPG alone, it incurs a loss of Rs 751.14 a cylinder.

Wind-solar hybrid power system in the Hariharpurgadi village of Sindhuli district, financed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Wind-solar hybrid power system in the Hariharpurgadi village of Sindhuli district, financed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Solar and wind

Various studies suggest Nepal has great potential in solar energy, but the country has yet to realize this potential. It is said that Nepal can generate up to 50,000 terawatt of solar power annually–100 times what can be generated from our rivers and 7,000 times the current electricity consumption.

Anecdotally, solar panels were first installed at Bhadrapur Airport in Jhapa district in 1962. Officially, solar panels officially came into operation from Damauli Telecommunication Office (then Aakashbani) in 1975.

Solar energy started off as a household energy source before recently making its way to the national grid–where it is making only a small contribution.

In 2020, the government inaugurated the first phase of its first 25MW solar array that feeds electricity directly into the national grid, in what is the biggest among the four large-scale solar power plants the NEA has launched. A few other private entities are also contributing to the development of solar energy in rural areas via community-based projects. Some of them send the surplus power to the national grid.

According to new laws, any household can produce electricity (without installing batteries) and send surplus energy to the nearby national grid. But many people are unaware of this scheme due to lack of publicity.

“Say, 100,000 houses of rich people in Kathmandu install solar panels. In that case, the surplus energy they generate could meet a sizable chunk of the valley’s energy needs,” says Jagan Nath Shrestha, a solar energy expert.

Part of why solar energy is not attracting investment in Nepal, Shrestha says, is the pricing.

“The price of a unit of solar electricity was Rs 9. But the rate was inexplicably reduced to Rs 6 a unit. At this rate, it may not be viable for the private sector to supply to the national grid,” he adds.

As for wind energy, Nepal is still in its early days. While the AEPC has installed wind turbines in a few areas, they are not completely wind-driven. As wind flow is not uniform across Nepal, these power stations also rely on solar energy.

A couple of decades ago, wind turbines were installed in Mustang district. But they were damaged due to excessive wind.

“The private sector is not interested in wind-power as there is no security of their investment,” says Madhusudhan Adhikari, executive director of the APEC.

A biogas plant installed in a house of Madhes province | Photo: Renewable World

A biogas plant installed in a house of Madhes province | Photo: Renewable World

Biogas

Most rural households in Nepal still rely on firewood for cooking. Energy experts and environmentalists see biogas as a viable alternative to this. Biogas is a form of clean, eco-friendly source of renewable energy which is both economically and environmentally viable.

It is produced from organic waste and can be used for multiple purposes. For example, the slurry that the biogas system produces is a convenient source of organic fertilizer. The energy of biogas could also be used as a fuel for heating purposes other than cooking. It can be compressed, much like natural gas, and used to power motor vehicles as well.

The commercial beginning of biogas in Nepal can be traced back to a program carried out by the United Missions to Nepal in the context of the Agricultural Year 1974/1975. The Agricultural Development Bank Nepal assisted in financing the plants by providing a special credit framework and established the Gobar Gas Company in 1977.

Biogas technology can also generate plenty of green jobs in Nepal. Most villages in Nepal have biogas plants. Studies show that biogas plant installation goes hand in hand with the improvement in local health and sanitation measures, while also curbing deforestation.

But biogas use is not widespread, with firewood still the main source of cooking fuel in rural Nepal.

Even when 1.4m rural houses of Nepal can potentially use biogas technology, only half a million households have installed it, says Shekhar Aryal, chairperson of Biogas Sector Partnership-Nepal.

“The cost of biogas technology, with nearly Rs 100,000 needed to install a plant, has increased with time, which in turn has reduced its attractiveness for villagers,” he says.

“This technology will live up to its potential only when the government gives them enough subsidies,” Aryal adds.

Dhundi Raj Pathak: Our approach to waste management is all wrong

The Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC) has restarted collecting waste following an agreement with the residents of Nuwakot district’s Sisdol and Bancharedanda, two sides selected for the disposal of Kathmandu valley’s solid waste. But many reckon it is only a matter of time before Kathmandu’s garbage problem will rear its ugly head again. Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talked to Dhundi Raj Pathak, a geo-environmental engineer and solid waste management expert, to get some insights into the issue.

Why hasn’t Kathmandu found a sustainable way to manage its solid waste?

Our ‘collect-and-dump’ approach has created a never-ending waste management crisis. Three decades ago, the majority of our solid waste used to be organic and the people of Kathmandu used to make fertilizers from them. It was a sustainable way to manage household waste. Yes, there were hygienic issues as waste materials were being managed at home. But there are ways to manage waste in a more hygienic way, especially by improving and scaling up the technology.

Unfortunately, we stopped that practice and started throwing waste on the road and dumping it in containers for them to be taken to the landfill. The landfill is one of the last components of integrated solid waste management (ISWM), where only residual waste should be disposed of and that too via a scientific and sanitary process. We have been following the wrong waste management approach i.e. shifting a problem from one place to another instead of adopting a sustainable ISWM approach for decades.

Who do you hold responsible for this state of affairs?

Every one of us. People don’t segregate their waste at home, nor do the local government and private companies collect and transport the segregated waste separately. Similarly, the federal government seems least bothered with the capital city’s waste management problem. None of the government recognizes solid waste management like urban infrastructures and has not made any investment in the treatment and recovery of solid waste over the past three decades.

Private companies also followed the same path that municipalities enjoy. They collect waste and dump it at Sisdol without focusing on resource recovery and service improvement. Gokarna, the first landfill for Kathmandu valley, was shut down for various issues. The KMC then designated Sisdol as a temporary landfill site for two years in 2005, with a permanent one proposed at Bancharedanda. The proposed landfill was never completed and the city continued to dump waste at Sisdol. We have overused Sisdol and overstayed our welcome there. That’s why the KMC repeatedly runs into a conflict with the Sisdol residents.

Is there a more sustainable way to manage our waste?

Solid waste management is not only a technical issue; it is also a social and managerial issue. We need both soft (capacity-building and behavioral change) and hard (investment in waste treatment and recovery/recycling facilities) interventions. In the past, we did either only soft interventions (campaigns) or we invested in infrastructure, without much planning and study. So we ultimately remained in the same position without finding a sustainable solution.

Moreover, the selection of waste treatment technology and process of waste management we adopt for (technically feasible and economically viable) depends on the amount and types of waste we produce. Different countries do it differently. Compared to more developed countries, we have a different kind of waste. We have more organic waste with high moisture content; they have more dry wastes like plastics, and papers with high calorific value.

Before the 80s, landfilling was popular but it caused environmental pollution. Also, the rapid urbanization reduced the suitable lands forcing people to seek alternatives. European countries and Japan once used incinerators to reduce the volume of waste and convert the mixed waste to energy through incinerators. But it affected public health and the environment as those machines were the main emitters of cariogenic gasses.

Since the 90s, those countries shifted their waste management strategies from waste disposal to recycling and recovery of waste as resources which Nepal can follow strictly. However, it doesn’t mean that we no longer need landfill sites. The fact is if you follow the waste management hierarchy appropriately i.e. reduce, reuse, recycle, and recover, a significant amount of waste can be diverted from landfilling and only residual waste should be sent to the landfill site. What we should do in the first step is segregate the solid waste into biodegradable and non-degradable materials at the source.

Separate collection, transportation, required treatment and recovery is a must for proper waste management.

The decentralized solution is handy for the small and less urbanized municipality however the centralized solution would be an appropriate solution for the highly populated cities, like Kathmandu where the availability of land for ISWM facilities is very crucial. Large-scale composting to produce fertilizer is the preferred option considering the huge demand for organic fertilizer and the potential for import substitution. As an alternative to recover the resources from organic waste, waste to energy (biogas plant) for treatment of source-segregated biodegradable waste can be established to generate energy in the form of methane gas. This option doesn’t only recover energy from the biodegradable fraction of solid waste but also provides compost fertilizers.

For non-degradable dry waste, increasing the recycling rate is the most preferred option but this requires more investment for infrastructures. Not only for managing massive amounts of solid waste in a sustainable manner but also for making it a profitable business, larger investments and a business vision is important. This is where the competent private sector and investors should step in. The private sector should take care of waste management where the local government should act as a regulatory body.

Do you think we lack good waste-management policies?

I don’t think so. Our plans and policies are up to date. Where we are lacking is in their implementation. It may be because of low vision, willpower, and confidence in leadership. Without a functional institutional arrangement, no policies could be implemented.

It is important that all solid waste management stakeholders should have collective efforts to find a sustainable solution to this problem. As of now, the first two tiers of government have not provided any technical support to municipals which is a major mistake. A competent federal unit is hence required to assist local levels in all aspects of solid waste management, especially in policy formulation and development of guidelines.

I learned that the new national solid waste management policy was recently approved by the cabinet and now needs the revision of the solid waste management act, 2011 in the context of three tiers of governments as well as to address a new stream of waste. Moreover, we should introduce investment-friendly policies and plans to attract the private sector for this business with a focus on resource recovery and establishing recycling facilities. Extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws should be introduced to make manufacturers responsible for managing the use of single-use and low-grade plastics as they are either expensive to recycle or can’t be recycled at all.

What do you suggest stakeholders do?

Collection coverage should be largely extended in the local units of Kathmandu valley and safely transport and disposal at the Bancharedanda landfill site by following sanitary landfill operational guidelines should be mandatory. Also, improvement in the collection and transportation systems with the recovery of resources from waste to reduce its amount at landfill should be implemented. For this, the people (waste producers) should segregate waste at sources at least in biodegradable and non-degradable fractions and keep it at the proper place inside their house premises before collecting by respective service providers.

Biodegradable waste has to be managed at the source through household composting to make fertilizers if possible. The municipality as well as authorized private companies should collect and transport source-segregated waste separately as per the schedule and treat it in the municipal level treatment plants. The federal government should provide the land where the municipality can build and operate waste treatment and recovery/recycling infrastructures in partnership with the private sector.

If we follow all the procedures, only residual waste (almost 30 percent of total amount) is what remains to be managed at the sanitary landfill site. Simultaneously, the post-closure and land utilization of Sisdol dumping site should be carried out to reduce existing adverse impacts on the public and the environment.

As for Sisdol residents, the problems they raised are always valid, and their protest is legitimate, but they have been making irrelevant agreements every time. As a result, the real victims are deprived of justice but a few ill-intended so-called victims have received the advantage while the government has made several agreements just for crisis management instead of problem solving. They should ask for a proper operation of the landfill site—one that does not endanger their health and environment. They instead bargain for jobs and physical infrastructure. If the site is managed as per standard, environmental compensation for the affected area should be distributed for the development and income generating activities of local people on priority basis.

A shorter version of this interview was published in the print edition of The Annapurna Express on June 16.

Tracking Nepal’s monsoons

Every year during the monsoon, Nepal suffers heavy loss of life and property in rainfall-related disasters. Natural as well as human activities are responsible for floods and landslides at this time.

Nepal is situated on the lap of the Himalayas, which are young, tectonically-active mountains with fragile geology. This geographical placement makes the country susceptible to landslides and erosion. Natural erosion process, pore water pressure, and geological conditions are the major drivers of landslides. Moreover, repeated earthquakes have destabilized the rock mass and loosened the soil of the mountains, further increasing the risk.

Add to this, the haphazard construction of roads and settlements on hills and mountains, and you have a recipe for disaster.

Erratic weather patterns, often attributed to climate change, have also increased the number of rain-related disasters.

Early start and late withdrawal of the monsoon has become common in recent years, which scientists and meteorologists ascribe to climate change.

Pre- and post-monsoon periods in Nepal are seeing more than average amounts of rainfall.

On average, Nepal receives more than 80 percent of the total rain during the monsoon season (June-Sept) alone. The normal onset of the monsoon is June 13 while the withdrawal date is Oct 2–or after 112 days.

Ideally, 1,470mm of rainfall during these four months is considered normal. But this year, meteorologists say, the monsoon arrived on June 5, eight days earlier than its normal date. The Department of Hydrology and Meteorology has forecast heavier-than-usual rainfall.

Compared to the normal, the duration of the monsoon was longer last year and the year before as well.

The rainy season lasted for 126 days in 2020; it was 122 days in 2021. The longest monsoon in the past 25 years was recorded in 2008, at 129 days. Nepal received 1,558.4mm rainfall in that monsoon. The wettest monsoon, however, was 1998 when the country received 1,806.7mm rainfall.

In 2006, monsoon arrived almost 11 days earlier on June 1 but ceased on Sept 29, much sooner than the normal withdrawal date. The shortest monsoon was in 2002 when the season concluded on Sept 19. Still, the country that year saw 1,463mm rainfall (seasonal normal).

As weather gets more and more unpredictable, it is getting difficult to plan and implement effective disaster reduction responses.

Meanwhile, lack of preparedness and resources has added to Nepal’s vulnerability to rain-related disasters.

Monsoon comes with both positives and negatives

Sanot Adhikari, Environment expert

There is no way to specify exact monsoon dates. If the calculation is off by a few days, it is considered normal. However, things could go wrong if the onset date is almost a week earlier. This is regarded as an untimely start of the monsoon, and it could invite many rain-related disasters.

Intensity, amount, and precipitation patterns also determine the consequences of the monsoon. For example, the onset date this year is the earliest in a decade. This could invite natural disasters like floods, landslides, and soil erosion. But if there is normal intensity and amount of rainfall and if the withdrawal date also came earlier, the damage will be limited. Rather, it will help with farming and irrigation.

However, the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology predicts that there will be more rainfall this season. Last year, the monsoon didn’t start too soon; yet, due to heavy rainfall (intensity) at the start of the season, there were devastating floods in Melamchi and other rivers.

Bhim Bahadur Thapa obituary: The man behind the perpetual search

Birth: 8 May 1920, Sindhuli

Death: 2 June 2022, Kathmandu

Bhim Bahadur Thapa, the man who left behind cryptic one-word message ‘Khoja’ in Devnagari script on streets, walls and electricity poles across the country, died on June 2 at the age of 104.

Thapa was a wizened old man of bent posture who wandered the streets and neighborhoods with a stick and a bag slung over his shoulders. He had this penchant of writing the word ‘Khoja’ (‘seek’) on whatever space he considered suitable with paint or chalk.

He was a man on a mission to make people seek knowledge and understanding human life.

Born to an ordinary family in Sindhuli district, Thapa never got formal education. He was an autodidact, who taught himself to read and write. At a young age, he became a passionate adherent of Karl Marx and his philosophy.

He believed in a casteless and classless society and joined the then Communist Party of Nepal in 1958. Thapa was an active participant in the communist movement of the time organized to protest against the monarchy.

During his years as a proponent of communism, he was detained on more than one occasion. But one day Thapa had a terrible epiphany: the communist parties of Nepal were faux-Marxists.

Disillusioned, Thapa left politics for good and in 1978 started his ‘Khoja’ campaign.

“Searching is an abstract thing, but it has made this world. Every other thing you see on earth is an outcome of searching, hence keep the spirit of search alive until you get your needs fulfilled,” Thapa once said.

One singular word ‘Khoja’ had a profound political, spiritual and philosophical meaning for those who meditated on it. This was what Thapa wanted: to get the attention of people with this simple word, make them pause for a moment–and think.

Thapa had fashioned his own flag for the campaign, with the word ‘Khoja’ with a cross of a pick-axe and hoe—in what was a clear indication of Marx’s influence on him.

To those who asked him about his work, he used to say that it was aimed against the feudal lords who exploited the masses. His goal was to organize his campaign around a group of adherents–just like Rup Chandra Bista did via his ‘Thaha’ movement in the 1970s.

Many people supported Thapa’s campaign, which lasted for a tad over four decades. But it never grew into a collective movement.

Thapa was against superficiality and insincerity. He wanted people to reflect, think, and most importantly, seek the truth.

That seeker of truth is now no more. Thapa is survived by three sons and seven daughters.