Fast track: Destroying Khokana

Around 96.47 percent of the land-acquisition process for the Kathmandu-Tarai expressway has been completed—save for the stretch in Bungamati and Khokana areas of Lalitpur district. The army says land-acquisition in these places have been halted over a compensation row. But the halt has more to do with the cultural significance of these areas.

As the town planning principles and traditional architecture of Kathmandu valley were transplanted to Khokana and Bungamati in the seventh century, these settlements represent not just a Newari townscape. They also have architectural, aesthetical, and symbolic values.

The expressway’s construction through these areas will destroy several heritage sites and ancient settlements. Besides the fast track, seven other projects are proposed in these areas. These “development undertakings” could further impact the local heritage, fear experts.

In 1996, King Birendra had proposed Khokana as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Today, the village is at risk, says Sanjay Adhikari, a public interest litigator for natural and cultural heritage.

“The 27-meter-wide expressway will destroy the proposed heritage site,” he says. “The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, of which Nepal is a signatory, as well as our constitution, advocate for the rights of indigenous people. But we are ignoring our commitment.”

Full story here.

Fast track: Destroyer of civilization?

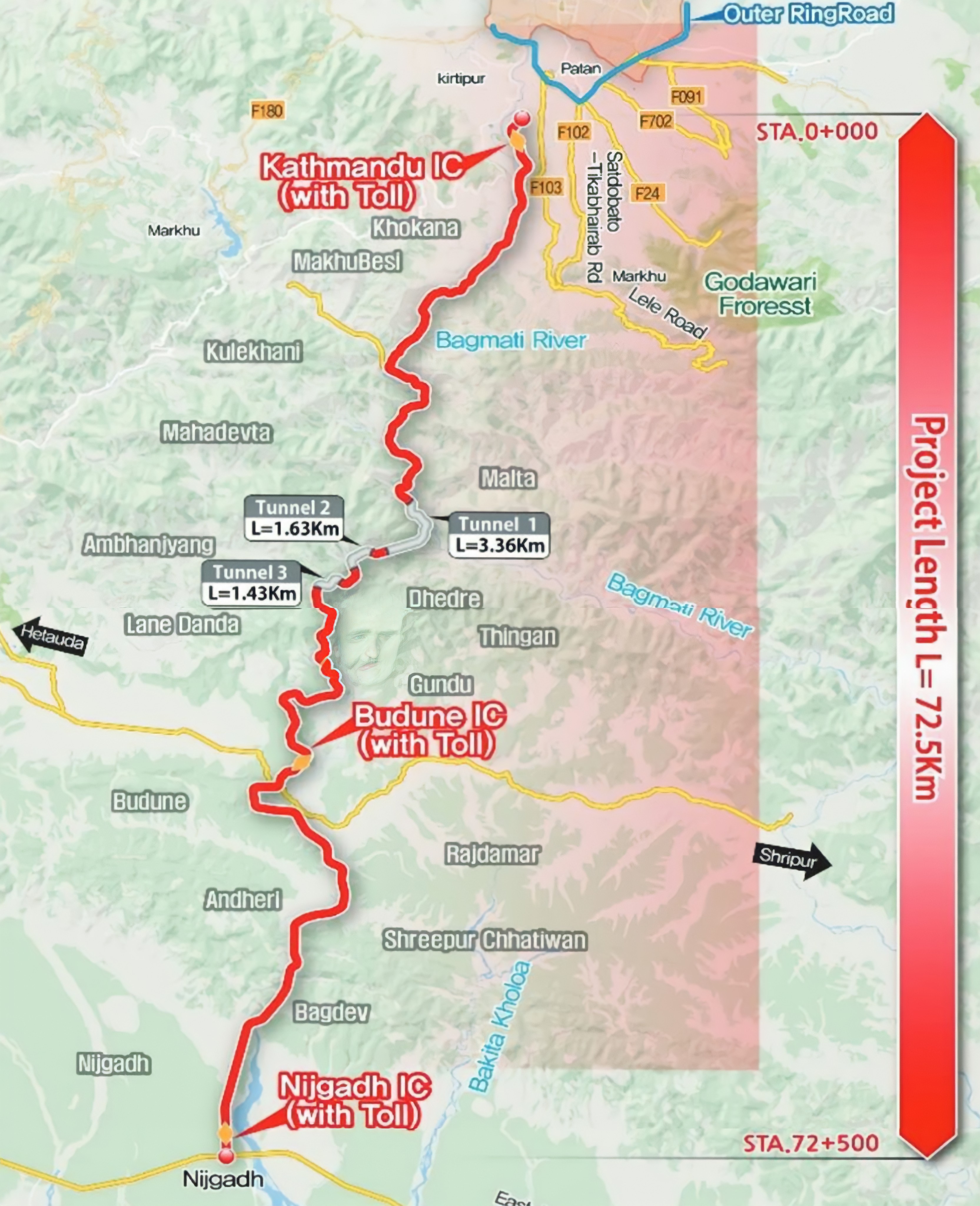

The Nepal Army, which has been constructing the 72.5km fast track to link Kathmandu with Bara district in the Tarai, says 96.47 percent of the project’s land-acquisition process has been completed. What remains unsettled are the properties in the Bungamati and Khokana areas of Lalitpur district.

The army says land-acquisition in these places have been halted over a compensation row. But the ground reality is different. The halt has more to do with the cultural significance of these two areas than land issues. The project’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) had hinted of the challenges of securing land for the 6 km-stretch of the expressway in Lalitpur. As the area is part of the ancient Newa heritage and a site of various cultural and religious ceremonies, the EIA report had given a heads-up to the project developer. As anticipated, there was fierce pushback from the residents of Bungamati and Khokana when the time came to open a track for the expressway.

As the town planning principles and traditional architecture of the principal cities of Kathmandu valley were transplanted to Khokana and Bungamati in the seventh century, these settlements represent not just a Newari townscape. They also have great architectural, aesthetical, and symbolic values.

Also read: ApEx Explainer: The what, where and when of the fast track

Earliest human settlement in the valley is thought to have started here. Naturally, the locals are against the expressway as they fear the fast track will obliterate their closely-guarded heritage and culture. Cultural experts say Bungamati and Khokana are home to Hindu and Buddhist socio-cultural values, and local arts and crafts industry. This heritage, they say, is sustained by the locals who still practice and celebrate ancient rituals and festivals.

The expressway’s construction through these areas will destroy several heritage sites and ancient settlements—and with them a civilization.

Besides the fast track, seven other projects are proposed and even being carried out in these areas. These “development undertakings” could further impact the local heritage, fear experts.

In 1996, King Birendra had proposed Khokana for the UNESCO World Heritage Site. In the proposal, Khokana was described as a unique village, a model of a medieval settlement pattern with a system of drainage and chowks. The mustard-oil seed industry was called the ‘living heritage’ of the village.

Today, the entire village is at risk, says Sanjay Adhikari, a public interest litigator for natural and cultural heritage who has been closely following the fast track project.

“The 27-meter-wide expressway will destroy the proposed heritage site,” he says. “The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, of which Nepal is a signatory, as well as our constitution, advocate for the rights of indigenous people. But we are ignoring our commitment.”

Also read: Army veers off the environment track

Bungamati and Khokana are well known for Rato Machhindranath and Shikali Jatra. These places are built in the shape of Swastika, according to Hindu mythology. The fast track could distort these features. Besides, there is also the risk of Katuwal Daha, a pool whose water is used in Rato Machhindranath Jatra, getting encroached, or worse, buried.

Similarly, Kumari Chaur, the courtyard of the living Goddess Kumari where the victory of Bhawani Devi is celebrated on the night of Navami, will be completely encroached by the fast track. The practice of Pahanchahre, a festival celebrated on the eve of Ghodejatra, will also stop.

The Newars of Khokana don’t celebrate major Hindu festivals like the Dashain. They rather consider Shikali Jatra as their biggest festival.

Also read: Lack of fast track progress raises questions over Nepal Army’s credibility

The construction of a fast track will erase these ancient villages, heritages and rare cultural practices, warns Nepal Man Dangol, who leads a struggle committee for the conservation of Khokana.

“Rather than solving the issues, the army, police, and government have been using force to suppress our movement to protect our heritage and culture,” he says. “We are determined not to allow them to resume construction here.”

Cultural functions performed in public spaces, religious structures, and agricultural lands are the foundations of these Newari settlements. The gradual shift in the economic base from agriculture to service and the demise of traditional social institutions were already endangering local culture.

Dangol fears the fast track could be the final nail in the coffin of their heritage.

Also read: What if… the fast track project was completed on time?

The fast track also violates article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that stipulates that everyone has the right to freely participate in the cultural life of the community, enjoy the arts, and share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

It also breaches article 15.1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and articles 7, 8 and 23 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

While the fast track could potentially put the ancient villages of Khokana and Bungamati in jeopardy, the impact of its construction elsewhere is starkly different.

In the village of Lendanda in Makwanpur district, which is just a 1.5 hours off-road drive from Hetuada, the fast track is viewed as a boon.

When the expressway comes into operation, they say it won’t take them more than 30 minutes to reach Kathmandu.

Also read: A whiff of partisan, geopolitical interference

“Not only will our access to hospitals and schools improve, we will also be able to build more of them right here in our own village,” says Biru Tamang, a Lendanda villager.

Roads connect nearby inter- and intra-communities with markets as well as health and education facilities. They also improve access to facilities like water, sanitation and electricity, create jobs and diversify sources of income.

Laya Prasad Uprety, professor of anthropology at the Tribhuvan University, says while road connectivity is vital to improve people’s living standards, it also comes with some negatives.

“Yes, roads can spur growth and improve people’s lifestyle, but they can also damage the culture and heritage of indigenous communities,” he says.

“Development also means an incursion of modern norms and values and they could displace indigenous culture,” says Uprety.

Rural areas, by and large, have acted as producer communities. The new infrastructures could turn them into consumer communities. There is also the risk of organic agricultural practices being displaced. For instance, it is hard to find organic agricultural produce these days as the seeds and fertilizers of multinational companies have penetrated all corners of the country.

“So, you see, the roads can be both a boon and a bane,” says Uprety.

Fast track: A whiff of partisan, geopolitical interference

Nepali political parties are experts at claiming credit, shifting blame and rewarding themselves while dealing with big development projects. Mothballing of projects started by the preceding government is also nothing new.

As ApEx takes a deep dive into the construction of Kathmandu-Tarai fast track, a national pride project, our team investigated behind-the-scenes maneuverings to influence the road’s progress for the benefit of certain parties, leaders—or even countries.

The 72.5km expressway linking Kathmandu valley with Bara district in the Tarai was envisioned decades ago. Work, however, started in earnest only in 2017 after the Maoist-led government handed the project to Nepal Army.

Earlier in 2014, the Sushil Koirala government had awarded the fast track to the Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services (IL&FS), an Indian company, a decision which was later challenged in the Supreme Court. The petitioners had deemed the project cost too high. In response, the court on 9 Oct 2015 directed the government to halt all related work.

China had also been unhappy with the Koirala government’s decision to give fast track to an Indian company, says a former secretary of the Nepal government requesting anonymity.

The subsequent CPN-UML-led government under KP Sharma Oli terminated all agreements signed with the IL&FS.

In the meantime, the army started lobbying for the project. Its stars were aligned with the next government led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal that was not in favor of an Indian company getting the mega-project. Dahal then chose the army to complete it. It was a wonderful opportunity for the Maoist chairman to rebuild ties with the army that had been badly strained following his 2009 sacking of army chief Rukmangud Katawal. Dahal is also rumored to have leaned on the army to involve Chinese companies in the project.

Also read: Army veers off the environment track

But since then such instances of clear favoritism have been hard to find in relation to the fast track.

Aman Lal Modi, a CPN (Maoist Center) lawmaker, says although the project started under the Maoist-led government, his party would not try to take all the credit.

Similarly, when CPN (Unified Socialist) Chairman Madhav Kumar Nepal recently inspected fast track sites, many saw it as posturing to impress his constituency in Rautahat, which is near Nijgadh, the expressway’s end point.

However, Unified Socialist lawmaker Parbati Bishunkhe also dismisses the allegation that Nepal was trying to make a “political statement”. “As a responsible politician and former prime minister, it is his duty to oversee the mega-project’s progress,” she says.

Several governments have come and gone since work on the fast track began in 2017, but the project—originally slated for November 2021 completion—is nowhere near done. Every year, billions of rupees are being allocated for it, but the army says the money is still insufficient. The cost overruns are, meanwhile, bleeding the state’s coffers.

Representatives of major parties tell ApEx that while there is no competition to take credit, the common concern was regarding lack of budget for timely project completion.

“Is it even possible to allocate enough budget for the project? This should be our primary concern, not whether this or that political party is trying to influence the project,” says Ganesh Kumar Pahadi, a CPN-UML lawmaker.

Nepal must invest 13 to 15 percent of its GDP in infrastructure over the next two decades to meet its development goals. On highways and roads alone, the government needed to allocate around $1.3bn in 2020. The eventual allocation fell well short of that. The country’s annual infrastructure spending is expected to reach $5.6bn by 2025 and $7.5bn by 2030. It’s clear that the government cannot finance infrastructure projects requiring such huge investments.

Plenty of money has already been spent. When Krishna Bahadur Mahara was the finance minister in the Pushpa Kamal Dahal-led government, he had allocated Rs 1.35bn for the expressway in the fiscal year 2017-18. His successor Yubaraj Khatiwada of the UML then allocated Rs 10.13bn, Rs 15.93bn, and Rs 15.01bn respectively in the subsequent fiscal years. All three of these latter allocations were revised to Rs 8.6bn, Rs 5.97bn, and Rs 4.46bn.

Then, former finance minister Bishnu Prasad Paudel of the UML allocated Rs 8.93bn for the project through an ordinance. The current Finance Minister Janardan Sharma approved the allocation in the latest budget.

But the army could still struggle to complete the expressway by the new January 2025 deadline. The estimated fast-track cost, initially projected at Rs 86bn, has already reached a whopping Rs 213bn.

With elections of all three tiers of government approaching, it would be difficult to allocate sufficient budget for the fast track in the coming years as well, providing the army another handy excuse to yet again push back the deadline.

The army’s work has not been satisfactory. There have been complaints over lack of transparency, violation of public procurement laws and breach of environmental regulations while building the expressway.

For instance, complaints have been filed with the Public Accounts Committee of the House of Representatives that the army hired a couple of Chinese companies for the project without due process.

This happened at a time when the Oli-led government had dissolved the lower house of Parliament in Dec 2020. As there was no relevant lower-house committee to file a complaint, the case was taken up by the National Affairs and Coordination Committee of the upper house.

“In the absence of the House of Representatives, the communist parties that favored the entry of the Chinese company let the army continue with the hiring process,” says a senior journalist who has been closely following the fast track project development.

But Radheshyam Adhikari, a former National Assembly member from the Nepali Congress, denies wrongdoing on the part of political parties. Adhikari was in the assembly’s National Affairs and Coordination Committee when it investigated the complaint against the army.

“We studied the case thoroughly and made recommendations in line with national interest,” he says. “We believe the national pride project is good for the country and its citizens and it shouldn’t be stopped at any cost.”

DishHome introduces ‘Mega-Fi’

DishHome, Nepal’s cable service provider, operated by Dish Media Network Ltd. has also been providing advanced and innovative internet services to customers since 2020.

Since DishHome entered into the internet market, it has routinely upgraded its features and products to satisfy the needs of its customers, providing fast, affordable, and reliable technology.

It now has come up with an upgraded package ‘Mega-Fi’ that aims to reinforce modernized communication facilities within the nation that comes with stronger and faster internet coverage than regular Wi-Fi routers.

Here are the new products of DishHome Fibernet with their specifications.

Single Band Router

The Single Band Router broadcasts with 2.4 G to provide a wider Wi-Fi range and support multiple Service Set IDentifiers (SSIDs). It comes with features of 1x1G 3x100M Ethernet ports with 5 dBi Antenna Gain. It comes with an internet package.

Features:

• 1x1 G 3x100 M Ethernet ports

• Supports 2.4 G

• 2 x 2 MIMO (Multiple-Input Multiple-Output)

• 5 dBi Antenna gain

• Supports multiple SSIDs

• Wider Wi-Fi range

Wi-Fi Extender

The Wi-Fi extender device is used to expand the reach of wireless Local Area Network (LAN) with the support of both 204 GHz and 5 GHz. The device can be easily plugged into the wall to bring a high-power Wi-Fi network coverage to any weak network areas around the home. The Extender DH-Fibernet router can be purchased from a nearby DishHome merchant for Rs 4,500.

Features:

• Extends Wi-Fi signals

• Supports 2.4 G and 5 G

• High power Wi-Fi amplifiers

• Easy wall-plug design

• B/W up to 1200 Mbps

• Improved signal performance

Dual Band Router

The Dual Band Router of DishHome Fibernet supports 2.4 G in addition to the 5 G frequency band which means they support the aggregate speed required for IPTV 4K video. It comes with an internet package.

Features:

• 1x1 G and 3x100 M Ethernet ports

• Supports 5 G and 2.4 G

• 2 x 2 MIMO

• 5 dBi Antenna gain

• 2.4 G and 5 G concurrent

• Supports multiple SSIDs

• IP1V 4K Video support

Wi-Fi Mesh Network Extender

The Wi-Fi Mesh Network Extender is a form of Wi-Fi booster. It is a smart-whole-home-Wi-Fi system with a single SSID that widely covers the network with a smooth and seamless Wi-Fi signal. It can be purchased from any DishHome dealer for Rs 5,000.

Features:

• Smooth Wi-Fi signal

• Seamless roaming (Single SSID)

• Smart wide coverage

• Easy use with LinkHome (an app developed by Huawei to manage home gateways and home networks)

• Band steering selects a faster Wi-Fi frequency

• 3x1 G Blind-mate Ethernet ports

• Build in Wi-Fi repeater to expand coverage

Wi-Fi 6

DishHome Fibernet comes with Wi-Fi 6 with greater speed and better connectivity with secured internet access from the router to the devices. For users with VR devices or multiple smartphones, the DishHome Wi-Fi 6 is an easy router to connect to the internet. It is available with the internet package.

Features:

• Wi-Fi 6 Gigabit router (802.1ax lot)

• Air interface rate up to 3000 Mbps

• Parental control and secured internet access

• 4x higher Data Rate (DAM 1024)

• loT friendly (connects up to 64 devices to Wi-Fi network)

• IPTV Ultra 4K video and VR support

4K Streamer

It is a recently launched product of DishHome suitable for gaming and surfing other applications. For the quick search and connection, it comes with a smart remote-control feature and ok google setups. It costs Rs 8,999.

Features:

• 4K Ultra HD

• Built-In Chromecast

• Ok Google feature

• Smart remote control

• Dolby audio system

• Games and other apps

• Bluetooth 4.2

• Certified Android TV

Fast track: Army veers off the environment track

The under-construction Kathmandu-Tarai fast track passes through 30km of agricultural land and 43km of forest cover. The project’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), approved in 2015 foresees physical, biological, socio-economic, and cultural impacts from expressway construction. These impacts, the EIA estimated, would be particularly high in 38 villages that lie within 50-meter distance of the road development sites.

The EIA report also suggests measures to mitigate potential risks.

On its website, the Nepal Army, which is building the fast track, has put the EIA under the project’s ‘salient features’ category. It claims environmental concerns were fully addressed during the project’s planning, preliminary design and alignment phases. It also guarantees continuous monitoring of project sites and assures necessary steps will be taken for environment-protection and impact-mitigation.

Based on these commitments, the army, in late 2021, submitted a supplementary EIA report, which was later approved by the Ministry of Forests and Environment.

But the report clashes with ground realities.

During a recent ApEx field-reporting trip of the expressway, our team spotted several unaddressed EIA concerns.

Also read: Lack of fast track progress raises questions over Nepal Army’s credibility

As we reported on March 10, some Chinese workers had chopped down almost a dozen trees without any permit at Bandarekholchha of Makwanpurgadhi Rural Municipality in Makwanpur district. The army camp set up to liaise with the local community on fast track-related concerns had mostly ignored the villagers’ complaints.

In the same place, the army has cut off half of a hillside atop which sits a small village. This has exposed the village to landslide and erosion risks, once again suggesting the flouting of the EIA directives. But the army denies any oversight.

Brig. Gen. Bikash Pokharel, the fast track project chief, dismissed our findings and denied the EIA protocols were violated. He even refused to accept our photographic evidence.

The army has felled over 27,000 trees while opening the expressway-track. There are 13 community forests and several other national forests in project areas.

As the expressway doesn’t cut through dense forest areas, there is unlikely to be much destruction of wildlife habitat. But, at the same time, the potential destruction of endangered species of natural flora cannot be disregarded.

Pollution is another environmental concern that seems to have gone unnoticed.

Residents living near fast track construction sites told ApEx that their earlier peaceful lives had been disrupted by the noise and vibration from earth-movers and other machines.

“We have to listen to this racket all the time. It’s unrelenting: construction happens day and night,” says Hikmat Tamang, a resident of Makwanpurgadhi Rural Municipality.

Residents close to the project sites also complain of deteriorating air quality. They say dust and dirt particles emanating from drilling, quarrying and blasting have polluted ambient air. Excessive dust particles have also harmed the crops of local farmers who rely on cash crops like pear, banana, maize, wheat and lapsi for their livelihood.

Also read: What if… the fast track project was completed on time?

Health experts say such constant noise and pollution could lead to physical and mental health problems.

“Continuous noise pollution could increase the risks of anxiety, psychological stress, depression, as well as high blood pressure, heart disease and stroke,” says Dr Rishav Koirala, a psychiatrist at Grande International Hospital.

But the army does not seem to have made any effort to rein in pollution at the project sites.

“You must water the construction sites twice a day to minimize the volume of dust in the air,” says environmentalist Aananda Bhandari.

Prohibiting open storage and spillage of loose soil, covering trucks carrying construction aggregate, and use of quality vehicle fuel and filtration systems could also help reduce air pollution.

Similarly, banning pressure horns, using noise barriers and silencers on vehicles and crushing plants, and limiting the use of explosives could minimize noise pollution. Planting of tree species such as the Ashoka is also useful in absorbing noise and air pollutants.

However, in many places, none of these mitigation measures seems to have been employed.

Bhandari thinks the expressway has been particularly egregious in neglecting environmental concerns compared to Nepal’s other mega projects.

“Apparently, as the fast track runs through small villages and only thin forest areas, perhaps the army does not think it will have much environmental impact,” he says. “But when it comes to preserving the environment, there should be no compromise. We should ask the army to strictly adhere to the EIA protocols.”

Also read: Fast track, off track

According to the EIA report, water quality at the project development sites was already poor, unsuitable for drinking or irrigation. The project has had relatively little impact on water resources. Still, the army has ignored the mandatory installation of wastewater treatment plants at project sites.

The only thing the army seems to be doing to protect the environment on a consistent basis is regularly disposing of the excavated waste.

Yet the army insists the fast track has not violated any EIA guidelines.

Officials at the Ministry of Forests and Environment also say there have been no reports of environmental concerns.

“We have not received any such complaints over the project on our regular inspections,” says Megh Nath Kafle, the ministry’s spokesperson.

When ApEx shared some examples of potential environmental breaches, he committed to unearthing the truth soon.

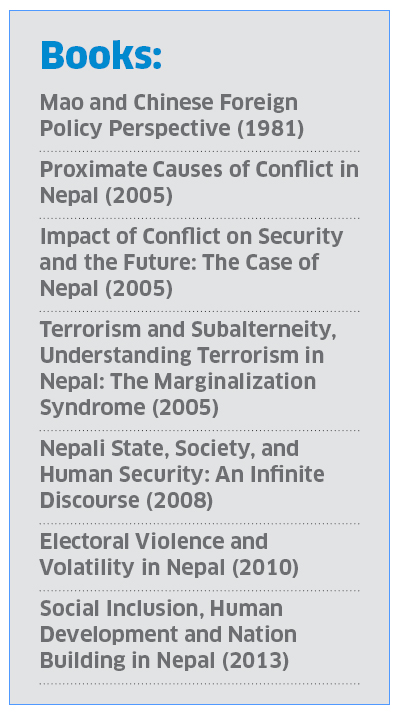

Dhruba Kumar obituary: A towering scholar

Birth: 1949, Kathmandu

Death: 16 March 2022, Kathmandu

At a time when most Nepali professors, intellectuals and civil society leaders like to attach themselves to political parties to curry favors, Prof. Dhruba Kumar, who died aged 73 on March 16, was a rare exception.

He was an inspiration for the advocates of democracy and human rights. Prof Kumar was among the few intellectuals in the country with vast knowledge in foreign, defense, geopolitical and strategic affairs. Crucially, he possessed the rare knack of explaining these complex topics to the public with clarity and simplicity.

All his life, Prof. Kumar was an ardent champion of equality and social justice. He was against all kinds of discrimination and never used his surname in his journals, books and columns.

Despite being a profoundly learned man, he never had an air of self-importance.

A retired professor of Political Science at the Center for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS), Tribhuvan University, he was a passionate researcher on the politics of South Asian countries.

More recently, Prof. Kumar’s columns focused on relations between Nepal, India and China, where he discussed India’s ‘hegemonic tendency’ and China’s ‘silent tactics’.

Prof Kumar began as a China scholar at CNAS and gradually expanded his study and research in other South Asian countries, becoming one of the authorities on the region’s strategy, diplomacy, security and geopolitics.

His fellow professors at CNAS remember Prof. Kumar as an inspiration for all scholars.

“He was the one to start the culture of academic research on security affairs,” says Krishna Khanal, who had worked with Prof. Kumar at CNAS. “He was also a pioneer in the study of Chinese politics.”

In his academic career, Prof. Kumar wrote many books on foreign affairs, conflict and security. He also participated in fellowship professor exchange programs in universities around the world. He was a FCO Fellow at the Department of War Studies in King’s College London, England; Ford Visiting Scholar at the Program in Arms Control, Disarmament and International Security in University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign, Illinois, USA; and Visiting Fellow at the Faculty of Asian and International Studies in Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia.

Prof Kumar worked as a full-time professor at the School of International Development and Cooperation (IDEC) in Hiroshima University, Japan. In 2002, he was a member of the SEAS 2002 Conference that was jointly sponsored by the US Commander-in-Chief Pacific (USCINCPAC) and the Department of State for Security Professionals of the Asia/Pacific Region.

He is survived by his wife and three daughters.

What if… the fast track project was completed on time?

A Kathmandu-Tarai expressway to link the valley with the Tarai plains via the shortest-possible motorway was conceived decades ago.

But the idea didn’t come into fruition due to various technical, political and financial hurdles. Then, in 2017, the then Pushpa Kamal Dahal-led government officially handed over the project to the Nepal Army.

The initial deadline of the expressway was Sept 2021 but was extended to Jan 2025 due to lack of progress: the army has completed just 16.10 percent work till date.

As work on one of the country’s flagship infrastructure projects sputters on, a dwindling number of people believe the fast-track, even if completed someday, will have the desired impact on development.

But how would Nepal have gained had the fast track been completed by its initial 2021 deadline?

First, says Uma Shankar Prasad, a member of National Planning Commission, the 72.5-km route would have drastically reduced the travel time between Kathmandu and Nijgadh of Bara district in the Tarai.

“This would have saved the country millions of dollars by reducing fuel consumption and vehicle maintenance cost,” he says. “We would have had a better balance of payment and smooth and fast transport would have contributed to our GDP.”

But a former secretary of the Nepal government, who has been closely following the project, does not see the expressway as economically viable.

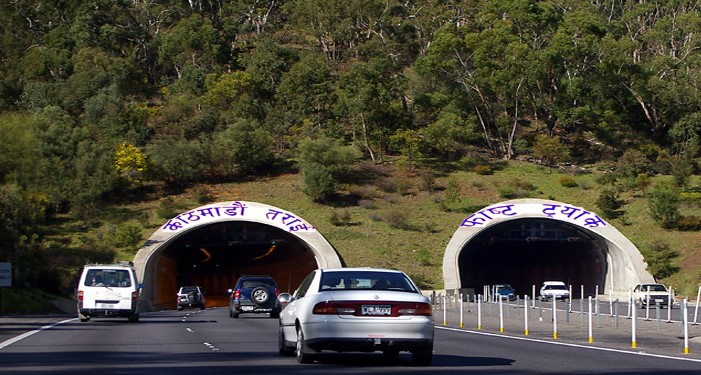

A concept picture of twin tube exit of Kathmandu-Tarai fast track.

A concept picture of twin tube exit of Kathmandu-Tarai fast track.

“There would have been no meaningful change even if the project was completed in 2021,” he says while requesting anonymity. “The fast track cannot generate profit and will thus be a burden for the government. He says the fast track’s passage through an earthquake-prone area presents additional challenges.

In fact, the burden on the treasury has increased.

The government in 2021 completed the construction of dry ports at Birgunj and Chobhar. They were built exclusively for the expressway. Had the fast track been completed earlier, the dry ports could have started generating revenue—rather than bleeding money as they currently are.

Due to inflation, the estimated project cost has risen from Rs 80 billion to Rs 175 billion. Moreover, the NPC now reckons the expressway could cost Rs 213 billion in current prices, reaching a high of Rs 300 billion by Jan 2025.

“Even in a straightforward calculation, timely completion would have saved us almost Rs 80,” says Chandra Mani Adhikari, an economist and former NPC member.

He says a completed expressway would not just have improved Nepal’s trade access, but also increased Nepal’s production and export capacities.

Research suggests Kathmandu-Tarai fast track would decrease national fuel consumption by 20 percent. “Even with the saving of 10 percent fuel, there will be a national saving of Rs 20 billion. This is important, given that Nepal imports almost Rs 200 billion worth of fuel a year,” says Adhikari.

A concept picture of twin tube entry of Kathmandu-Tarai fast track.

A concept picture of twin tube entry of Kathmandu-Tarai fast track.

The former government secretary does not agree.

“Japan and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) have conducted separate feasibility studies on the fast track. They suggest the route could be underutilized as there are many other road links between Kathmandu and Tarai,” he says.

Moreover, the estimated 90-minute travel time is applicable only for passenger buses and cars, not cargo trucks, which could take 5-7 hours to traverse the route.

Impact on other projects

Investing in Nepal’s mega infrastructure projects is widely considered unwise. The country lacks a good precedent. All 21 national pride projects are behind cost and schedule. The Upper Tamakoshi Hydropower Project, for instance, had an initial estimated cost of Rs 25 billion when the project began in 2011. It was supposed to be completed in 2018. When the deadline was pushed to 2021, the cost ballooned to Rs 90 billion. The Melamchi Drinking Water Project is also suffering a similar fate.

“Timely completion of the fast track would have set a wonderful precedent and could also have hastened work on other national pride projects,” says Govinda Raj Pokharel, the former NPC vice-chairman.

He says timely completion would also have helped attract investors to other important projects.

The airport link

The proposed Nijgadh International Airport is another project directly linked to the Kathmandu-Tarai fast track. Experts say the two projects were pitched around the same time, as they complement each other.

Pokharel, the former NPC vice-chairman, says timely completion of the fast track would have added impetus to the airport project.

“It would have put pressure on concerned parties to expedite works on the airport, which, when complete, will naturally boost traffic on the fast track,” he says.

For now, the fast track project drags on with no certainty of whether the army will require further deadline extensions.

Binoj Basnyat, a retired Nepal Army major general, thinks the army made a strategic miscalculation by accepting the fast track project, which has dented its credibility.

“The project’s timely completion would have enhanced public faith in the army. But the reverse is also true: the army’s competence is being questioned over the long delay on the fast track,” he says.

Lack of fast track progress raises questions over Nepal Army’s credibility

An ApEX team was recently on a field-reporting trip of the Kathmandu-Tarai Fast Track Road Project. Our objective was to document progress on the 72.5km expressway that will connect Kathmandu valley with Bara district in the Tarai, considerably cutting time and distance between these economic fulcrums of the country.

At a project site at Bandarekholchha of Makwanpurgadhi Rural Municipality in Makwanpur district, we spotted a villager arguing with a Chinese excavator operator.

Ram Bahadur Waiba, we learned, was angry about indiscriminate felling of trees. The stumps of freshly cut trees were before our eyes, and Waiba, despite the language barrier, was demanding an explanation from the Chinese worker.

“They [Chinese workers] have chopped down almost a dozen trees for which they have no permit,” Waiba told ApEx.

There was an army camp nearby to listen to and address the concerns of the people living in and around the project site. But Waiba said the army had ignored their complaints.

Also read: Photo Feature | Tracking the fast track road project

It was a clear case of the project contractor violating the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report. The army had already cut down the required number of trees in the area to make way for the fast track. Felling more trees is against the EIA mandate. The residents of Bandarekholchha told ApEx that neither them nor the forest department was informed before the trees were axed.

The army denies the EIA protocol was breached. In a press conference organized at the army headquarters on Feb 23, Brig. Gen. Bikash Pokharel, the fast track project chief, dismissed our finding that trees at Bandarkholchha had been felled. He even refused to accept our photographic evidence.

Pokharel instead claimed the fast track had created jobs for those living near project sites.

“For every Chinese worker, there are three Nepalis employed at the project sites,” he told the assembled media representatives. “Chinese workers, moreover, teach useful skills to their local counterparts.”

But the people we spoke to had a different experience. Most of them were unhappy with the way the army was managing the project. They said very few villagers were employed.

“Although this mega project has come to our village, we are not getting the promised jobs,” says Dinesh Moktan of Bakaiya Rural Municipality in Makawanpur. “We asked the army for more local participation, but our plea was ignored.”

There is still a lot of work to be done before the new fast track deadline of 2024 (the previous deadline was November 2021). The army itself reports 16.1 percent overall progress. Experts warn of further time and cost overruns. Some even question the idea of handing over fast track construction to Nepal Army. Their concerns emanate from alleged irregularities in the project that have cropped up time and again since the government commissioned the task to the army in 2017.

Semant Dahal, a lawyer who has closely studied the project, believes time has come to ask some hard questions. Given the paucity of progress in the past five years, “Do we still think it [the Army] is the most suitable entity to build such an infrastructure project?” he questions.

Also read: ApEx Explainer: The what, where and when of the fast track

In 2019, a probe had found that the evaluation criteria for the selection of consulting firms for the project had been leaked to potential bidders. The decision to select six international companies was scrapped over the leak, which the army termed a “technical error”.

The following year, a government review committee opened an investigation into the army’s alleged breach of the Public Procurement Act when it selected a Korean company as a project consultant.

Fast track construction was handed over to the army following an earlier controversy over the government’s decision to award the contract to Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services (IL&FS) of India in 2014. The contract dispute had reached the Supreme Court and the deal was ultimately ditched.

Meanwhile, the army was lobbying to secure the contract despite having no prior experience of working on large infrastructure projects.

The 2017 decision to award the project to the army had gotten a favorable response from experts and public alike. After all, it was the army that had opened the track for the expressway. Five years later, the army’s role is increasingly coming into question.

Experts and stakeholders are demanding transparency and accountability from the army as the project has run into delays and controversies. The fast-track cost, which was estimated at Rs 86 billion in 2011, has soared to Rs 213 billion. The army is in no place to assure that the project will be completed within the new deadline and reasonable budget.

The army’s lack of experience in big projects is perhaps a reason the fast track has been facing hiccups and delays.

Further, some say the schooling and institutional attitude of the army hasn’t changed much since the 90s—as the army was back then, it is still largely unaccountable to the authorities.

There have been numerous complaints against the army’s flouting of the instructions of parliamentary committees and other government bodies.

Also read: Fast track, off track

Bharat Kumar Shah, chairman of the Public Accounts Committee of Parliament, says the army just does not listen.

“We had asked the Nepal Army to halt bridge and tunnel works following some discrepancies in the bidding process, but it simply brushed aside our directive,” says Shah.

The army is also not helpful when it comes to sharing information, or supporting independent inquiry. Our team was repeatedly accosted and questioned by the army in the course of reporting at fast track sites. They demanded a permit from army headquarters to take photos at some sites—all public places.

Many experts ApEx spoke to (many of whom chose to remain anonymous) say that in retrospect giving the fast track to the army was a bad decision. They suspect the project was handed over to the army to avoid controversies, with most people trusting the institution to do the right thing.

Brig. Gen. Narayan Silwal, the army spokesperson, denies the allegations against the army. He says talks of the expressway being further delayed and incurring more money are all misinformed rumors.

“The national pride project is being built under the management of a disciplined institution,” he insists.