Dilli Raj Khanal: Central bank autonomy vital to keeping donor trust

The suspension of Nepal Rastra Bank Governor Maha Prasad Adhikari threatens to further roil an economy already battered by covid-19. Adhikari had apparently refused to heed Finance Minister Janardan Sharma’s instruction to release Rs 400m of suspicious money from abroad deposited into Nepali bank accounts of one Prithvi Bahadur Shah. (The Supreme Court on April 19 overturned the governor's suspension.)

The country’s foreign reserves have shrunk to alarming levels. Remittance and tourism—the two backbones of Nepal’s economy—aren’t doing well either. Moreover, Nepal is already in the international spotlight as a conduit of illicit money.

Kamal Dev Bhattarai spoke to senior economist Dilli Raj Khanal on the possible implications of the government’s intervention in the central bank and its lax attitude on black money.

What are Nepal’s international commitments on combating money laundering?

Global Financial Integrity, a Washington-based think tank, maintains a record of illicit financial flows, corruption, illegal trade, and money laundering. It also tracks money laundering in Nepal.

Likewise, the Asia Pacific Group on Money Laundering, a regional anti-money laundering body, conducts a mutual evaluation of the country. Nepal actively participates in such international organizations to control money laundering. But there seems to have been little improvement.

Money laundering is a serious business. That is why we have laws and agencies to deal with it. Nepal introduced the Money Laundering Prevention Act in 2008 and the Department of Money Laundering Investigation was established in 2011. But again there has not been expected progress. As money laundering is linked to a country’s image, Nepal should take sufficient preventive measures. We are being closely watched by international organizations.

In 2021, the Finance Ministry amended laws such that income sources of investors in infrastructure will no longer be investigated. Won’t that promote money laundering and flow of black money?

Obviously, it will. The provision says the government will not seek the sources of investments made in nationally important hydropower projects, international airports, and other projects that use more than 50 percent domestic raw materials. This is a wrong approach as it contributes to money laundering. Some argue it will boost investments. But I personally do not see this as a valid reason.

What will be the implications of reports of Finance Minister Janardan Sharma trying to release money brought into Nepal from suspicious sources abroad?

This is a very serious case, which could have a big implication on the country’s economy and image. The finance ministry is mainly responsible for checking the flow of black money. It has also formulated anti-money laundering laws.

With this incident, the ministry has sullied its image. Governor Adhikari has been suspended on charges of defying Finance Minister Sharma’s directive to give clearance to suspicious black money. This could spoil Nepal’s image abroad. Bilateral and multilateral donor agencies want a country’s central bank to be autonomous and its economy transparent. The autonomy of our central bank is vital to building trust with them.

What is Nepal’s international reputation when it comes to combating money laundering?

Many international reports suggest Nepal has a parallel economy and facilitates illicit flow of money. Our image was already bad abroad before the governor’s dismissal.

We are not fully implementing laws related to prevention of money laundering in order to improve our image and to earn trust of donor agencies and investors. On the institutional front, it is a complete mess. The finance ministry is mending in the business of other bodies.

If the Financial Action Task Force blacklists Nepal, what will be the consequences?

There will be multifaceted impacts. The country’s image in the international stage will further slide. Many developed countries, donor agencies and multilateral financial institutions take money laundering seriously. It will be tough for us to get loans and assistance from World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and other institutions.

It could also affect our international trade. If we fail to curb money laundering and flow of illicit money, it could in the long run create a serious economic crisis. Our politicians are taking this issue lightly, which is a grave mistake. Financial integrity is a vital pillar of any economy. If that is lost, it will affect every aspect of the economy, including resource mobilization, banking, and other sectors.

SAARC’s not-so-obvious issues

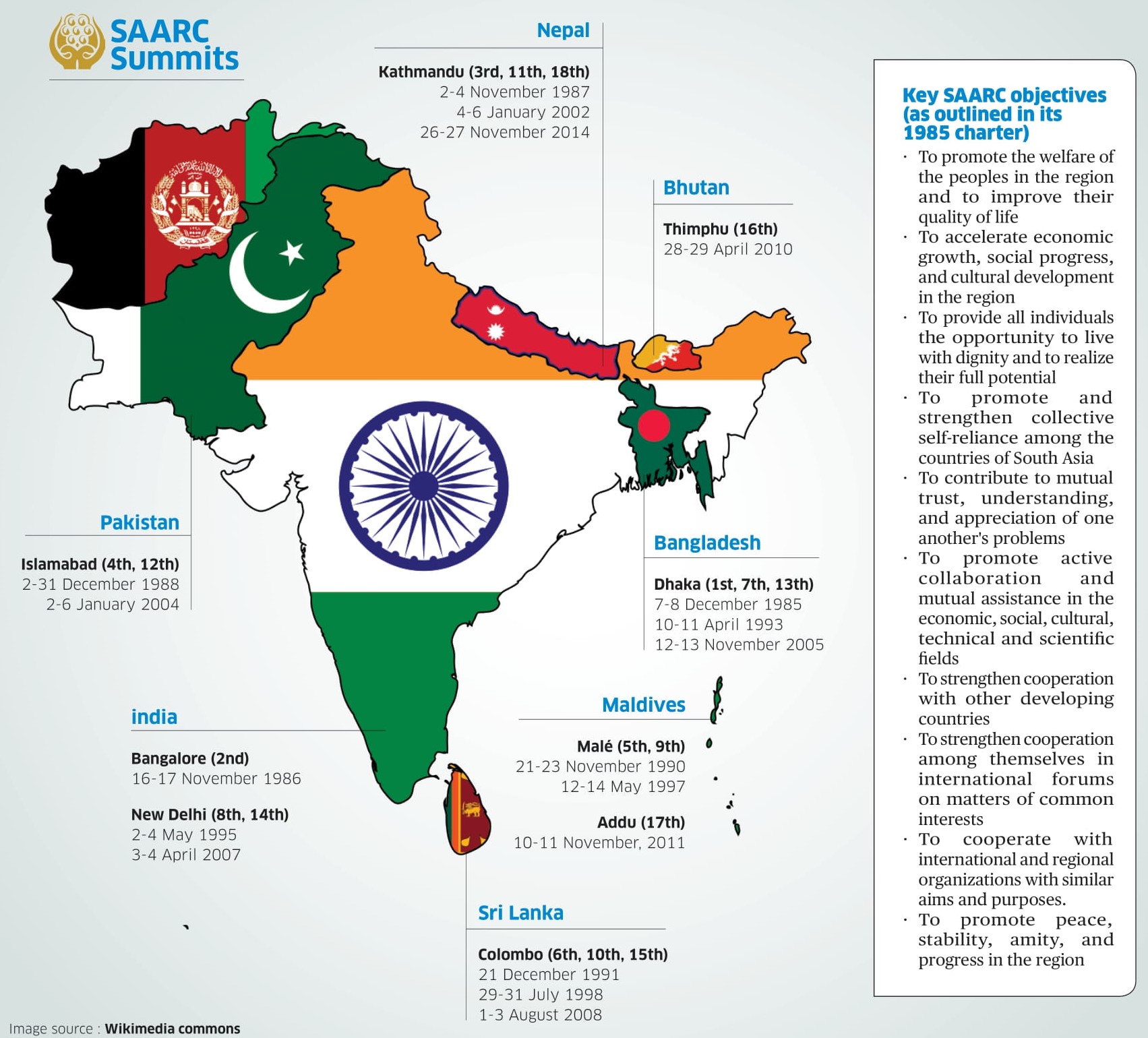

Age-old India-Pakistan tensions are often blamed for undercutting the effectiveness of the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC).

A good rapport between these countries, the two largest in the region in terms of population and military might, is imperative to give momentum to the SAARC process. But owing to bad blood between them the group’s biennial summit-level meeting has not been held after 2014.

International relations experts say the main reason behind the body’s sluggish progress is its failure to embrace the core principles of regional organizations.

For instance, the internalization of the notions of collective security, prosperity, and dignity by member states contributed to the success of the United Nations after the Second World War.

Shambhu Ram Simkhada, former diplomat and professor at Tribhuvan University, says international relations theorists had initially thought that a similar calculus would work at the regional level.

They argued that countries cannot conduct their foreign policy based only on narrow national interests and called for harmonization of national interests.

“Each country in a grouping has to understand that national interests will be harmonized so that individual country’s national interests are also served in a group-setting. That, at least, was the idea behind regional cooperation. But it could not take root in South Asia,” says Simkhada.

Over the past three-and-a-half-decades, SAARC, the regional bloc of eight South Asian countries, has largely failed to achieve its goal of economic and regional integration.

While the strained Indo-Pak relations could be the main reason behind it, there are other stumbling blocks as well.

Good organizations invariably have good leadership, something SAARC has long been missing. As its largest member with strong influence over its neighbors, India can (and should) take such a leadership role. But it has not been ready to do so.

With India unenthused about regional cooperation under SAARC, other member states have also not come forward to take leadership. Smaller countries can certainly take the lead to revive the stalled SAARC process. This was demonstrated by Nepal and Bangladesh in the 1980s when they played proactive roles in the regional body’s formation. They had convinced both India and Pakistan, which were initially unwilling to join, to come on board.

Amit Ranjan, research fellow at the National University of Singapore, says a regional body needs a leader who can lead through consensus.

“But India-Pakistan tensions and several other issues hinder such consensus,” he adds.

Stability is also a prerequisite for a vibrant and functioning regional cooperation. But political upheavals in member countries have constantly affected the SAARC process.

The SAARC summit could not be held from 1999 to 2002 following a military coup in Pakistan. Similarly, India withdrew from the 2005 Dhaka summit due to its differences with Bangladesh and King Gyanendra’s coup in Nepal.

Right now, barring India and Bhutan, all other South Asian countries are battling some sort of political instability.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban has regained power and the international community is yet to recognize it. Whether other member SAARC countries are ready to share the platform with Taliban representatives remains unclear.

Democracy-deficit in member countries has created hurdles for regional cooperation, say international relations experts.

Another factor hobbling the regional body is the tendency of member countries to engage bilaterally instead of prioritizing regional cooperation. On trade, connectivity, and environmental issues, India mostly engages with individual member countries bilaterally. SAARC has great scope in water and energy cooperation, but India is again dealing with these issues bilaterally, mainly with Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh.

India is also signing bilateral free trade agreements with the countries in the region rather than taking steps to operationalize the South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA).

“India is giving more attention to bilateral relations instead of working collectively through common platforms,” says Ranjan.

In her 2018 research paper ‘SAARC vs BIMSTEC: The Search for the Ideal Platform for Regional Cooperation’, Joyeeta Bhattacharjee, a senior fellow at Observer Research Foundation, a New Delhi-based think-tank, says bilateralism decreases the countries’ dependence on SAARC to achieve their objectives, making them less interested in pursuing region-level initiatives.

Bilateralism is easier as it entails dealing between only two countries, whereas SAARC—at a regional level—requires one country to deal with seven, she argues in her paper.

Preference for extra-regional trade and the general environment of distrust among member states have also diminished the scope of regional cooperation. Not only with Pakistan, India also has contentious issues with Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

The asymmetry between India and other member countries in terms of population, geography, and economy has made regional cooperation difficult. Smaller countries often see the projects forwarded by India as tools to cement its regional hegemony. This became evident in 2015 when Bhutan, Bangladesh, India, and Nepal agreed to a vehicle agreement, known as BBIN, only for Bhutan to later opt out stating that it cannot regulate the flow of people and goods. Pakistan had refused to join the initiative outright as it came from India.

Simkhada suggests boosting the status and widening the mandate of the SAARC Secretariat to create a more functional regional body. Right now, “SAARC is being treated as no more than a minor administrative body.”

The position of the SAARC secretary-general, he says, is lower than that of an ambassador or a joint secretary of any of its member states.

Insufficient economic resources have further hobbled the regional organization. Member countries are not ready to contribute large funds to finance big connectivity projects. At the same time, some member countries are opposed to receiving financial assistance from SAARC observer states like the US, China, and Japan or from other multi-national donor agencies.

For long, Nepal has been proposing active engagement with observer members to raise funds for big regional projects, to no avail.

A senior Nepali foreign minister official who has long been involved in the SAARC process and who spoke to ApEx on the condition of anonymity, says member countries, particularly India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh are against taking international support. They fear big powers or multilateral institutions could otherwise “impose their own agenda” in the region.

While member countries have divergent and disparate views on regional issues, there is no permanent mechanism to discuss them and bridge the differences.

“Disputes among member countries often hamper consensus building, thus slowing decision-making,” says Bhattacharjee. “SAARC’s inability in this regard has been detrimental for its growth.”

Over the past decade, China’s influence in the SAARC process and as well as in its member states has increased. China was brought in as an observer state at the request of member countries, including Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. This did not go down well with India.

Indian policy-makers fear China could use the regional body to make further inroads into its backyard. Experts say this is one reason India has shown little interest in SAARC’s revival.

A former Nepali diplomat who has closely worked with the Kathmandu-based SAARC Secretariat says Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan are for China’s greater role in the SAARC process, much to India’s chagrin.

“China itself has shown interest in playing a greater role within SAARC, and India most certainly does not want that,” he says. “This is one reason behind SAARC’s slow progress.”

BRI is not ‘a geopolitical strategy’ but a road to development: Chinese envoy

Chinese Ambassador to Nepal Hou Yanqi has said that BRI has never been a "geopolitical strategy" but a road to development.

Speaking at a virtual press conference on April 21, the Chinese Ambassador stated that BRI helps countries to achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and promote common development and prosperity. Speaking at the length, the Chinese diplomat clearly spelled out China's position on numerous bilateral issues that are in the public domain.

She began her speech by highlighting the geopolitical conflicts that are surging across the world.

At present, the COVID-19 pandemic drags on, geopolitical conflicts are resurging and the recovery of the economy remains sluggish and depressed. The peace, security, and development in the world are facing grave challenges, she said.

"Despite the complex international and regional situation, the China-Nepal relationship led and cared by the two heads of state, has maintained steady growth."

In recent years, the connotation and extension of China-Nepal’s BRI cooperation have been continuously deepened and expanded, the Chinese envoy added, a multi-dimensional promotion pattern featuring “hard connection”, “soft communication” and “heart exchange” and the all-around participation of the government, market and society is taking shape.

“The Trans-Himalayan Multi-dimensional Connectivity Network has gradually moved from a blueprint to reality. Since last year, the two sides have worked hard to overcome the huge difficulties caused by the pandemic and promoted the construction of BRI cooperation in various fields to achieve new progress,” she said.

Asked about the lack of progress in selecting specific projects under BRI, the Chinese diplomat made it clear that there are various types of cooperation under the broader framework of BRI which is moving ahead.

She was of the view that some already completed and under-construction projects are also under the broader vision of BRI. BRI cooperation between China and Nepal has not gotten bogged down because of COVID-19; on the contrary, it has become a road of hope that bolsters resilience and boosts confidence, she said.

When selecting and implementing specific projects, both governments and enterprises are required to follow the principles of openness, transparency, and friendly consultation with each other, she added. In recent years, China has paid more attention to the high-quality, green, and sustainable joint construction of BRI.

The Chinese Ambassador highlight the assistance provided by China to Nepal to fight Covid-19. Until now, China has provided around 20 million vaccines through grant assistance, commercial purchase, and other channels, making China the biggest supplier of the Covid-19 vaccine to Nepal.

Those vaccines have helped Nepal to fight against the pandemic and restored Nepali people’s life and work back to normal, she said. The Ambassador further stated that China will continue to provide vaccines and material support according to the demand of the Nepali side so as to help Nepal completely defeat the pandemic.

Over the past few years, there are criticisms that China is not cooperating with the smooth passage of Nepali cargo trucks at the border points, affecting the supply of goods. The Chinese envoy, however, dismissed such reports stating that trade between countries has not been much affected.

“According to the Chinese side’s statistics, the total volume of trade between China and Nepal increased 67% and reached $1.977 bn in 2021, of which Nepal’s export to China increased 63%. Those data proved that the so-call “soft block” on Nepal is totally baseless,” she said.

There are reports that Nepal's trade deficit is increasing and facing difficulties to export goods to China. She further stated that China has provided duty-free treatment to the goods of Nepali origin covering 98 percent tariff lines.

“Those are the efforts made by the Chinese side to increase Nepal’s export to China and will help relieve Nepal’s trade imbalance problem. We also welcome Nepal to attend China International Import Expo and actively promote the products that meet the demands of the Chinese market,” she remarked.

She elaborated in detail about the progress made so far in China-funded development projects. Stating that the two sides have signed the technical assistance plan for the feasibility study project of the China-Nepal Cross-border Railway Project, she said that it will further advance the projects. Similarly, she pledged to support Nepal in the promotion of the power grid interconnection, and build a new channel for Nepal’s power export.

She also shed light on the challenges of some development projects. “It must be pointed out that these projects will come across many difficulties such as complex geological conditions, frequent natural disasters, and high construction costs. This requires both sides to formulate practical plans on technical standards, funding sources, and so on in the spirit of seeking truth from facts,” she said.

About the early return of Nepali students and resumption of flights between the two countries, the Chinese Ambassador said that relevant authorities of both countries are working on it, and there will be positive progress soon. The Chinese envoy also raised the issues faced by Chinese enterprises in Nepal. Similarly, she raised concerns about the policy inconsistency in Nepal and its effects on bilateral cooperation.

“I also hope that the Nepali side could provide a fair and transparent business environment, fully protect the legitimate rights and interests of the Chinese enterprises, and help to solve their practical problems.” According to the envoy, currently, Chinese businessmen and enterprises in Nepal are facing many practical problems to carry out their work.

As China enters a new stage of development, we are actively implementing the new development philosophy and building the new development dynamic, she added, this will provide more development opportunities for countries around the world including Nepal.

China's development is also a contribution to the progress of all mankind. This is a common consensus of the international community and is supported and appreciated by the vast majority of countries, the envoy said.

Are Nepali celebrities discouraged from joining politics?

On April 6, actor Bhuwan KC announced that he would be standing for mayor of Kathmandu in the May 13 local elections, only to withdraw his candidacy days later. It has been over a decade since KC first expressed his interest in politics. He had also toyed with the idea of contesting the Constituent Assembly elections from CPN-UML in 2013.

KC tells ApEx he changed his mind about running for the mayor’s race this time after the Unnat Loktantra Party publicized his name as a candidate without his consent. But KC says he does plan on joining politics someday. Currently, he is not associated with any political party.

“Parties are using politics as a tool to either serve their own agendas or the interests of small groups. I want to join politics to address the problems of ordinary people,” KC says.

In the view of sociologist Ramesh Parajuli, unlike Nepal, India has a long history of celebrities winning elections, even holding ministerial posts.

In India, there are scores of celebrities—from actors like Amitabh Bachchan and Hema Malini to cricketers like Gautam Gambhir and Kirti Azad—who have joined politics to various degrees of success. This trend seems to be catching on in Nepal as well. Karishma Manandhar, Rekha Thapa, and Komal Oli are among the Nepali celebrities who have joined politics.

Some Nepali political parties have started actively courting celebrities. But whether they can transform their charms into votes is an open question.

In 2017, celebrated BBC journalist Rabindra Mishra contested parliamentary elections from Kathmandu Constituency-1. He lost to Nepali Congress candidate Prakash Man Singh by a narrow margin of 819 votes. But he comfortably came second, way ahead of candidates from CPN-UML, Maoist Center, and other more established parties.

Currently, no party seems as interested in bringing celebrities on board as UML.

On March 22, actor Manandhar joined the party amid fanfare. UML Chairman KP Sharma Oli himself welcomed her. In her remark, the actor said she was not going to bargain for any post in the party, and would be happy to serve as an ordinary cadre. UML hopes her stardom will help it pull some votes.

Since joining the party, Manandhar has attended quite a few events with Oli.

Popular folk singer Komal Oli is arguably the most successful celebrity-turned-politician in Nepal. She too joined the UML a few years ago and went on to become a National Assembly member.

After serving as a member of the upper house of federal parliament, she is now preparing to contest parliamentary elections from Dang Constituency-3.

Prakash Chandra Pariyar of Sajha Bibeksheel Party says there is certainly added charm when celebrities run for elections.

“Our old mainstream political parties have failed to deliver, so people gravitate towards new faces. And with celebrities, people can connect,” he says. “Celebrities with new vision and vigor could bring about some much-needed social changes. People want change.”

Celebrities’ embrace of politics could also help change common public opinion that politics is no more than a dirty game.

“If more celebrities join politics, we can minimize such a mentality, creating a positive atmosphere for all politicians,” says singer Oli.

Still, Nepal has a long way to go before a celebrity here can be a successful politician. It is still hard to imagine celebrities winning direct parliamentary elections. But why?

“What you see in India is that some of its celebrities represent language and cultural politics—that is not so in Nepal,” says social commentator Hari Sharma. With India’s gargantuan population, they invariably attract large followings. You don’t see the same kind of mass fan-base in Nepal.

“Usually, celebrities who want to succeed politically should have a solid social and cultural foundation but our celebrities lack such a foundation,” Sharma adds. “So I do not see our celebrities turning into successful politicians.”

Sociologist Parajuli says it is relatively easier for celebrities to join UML because it is a cadre-based party, and there is also some possibility in Madhes. “In the case of other hill- and mountain-based parties, it is not easy to contest and win elections,” he argues.

Echoing Sharma, Prof Ram Krishna Tiwari, head of the Central Department of Political Science, agrees that it is difficult for Nepali celebrities to establish themselves in politics.

“Ours is a highly politicized society, from the center to the grassroots,” says Tiwari, “and as such people tend to follow established politicians instead of new celebrity candidates.”

Tiwari adds that Nepali celebrities who are currently in politics also have no good vision.

Speaking on behalf of celebrities, both actor KC and singer Oli are skeptical about the commitment of political parties to ensure greater representation of celebrities in their ranks.

“As the election season draws close, politicians approach us and seek our help in their campaigns. But we are forgotten soon as the elections are over,” KC says. Arguing that Nepali political parties discourage the entry of celebrities into politics, KC laments the lack of realization on the part of political parties that “we are known and established faces who have won the hearts and minds of millions.”

National economy: Playing with fire

‘Is Nepal on its way to becoming another Sri Lanka?’ This question is being repeatedly asked, in the media and out on the street, as Nepal’s economic woes deepen. Many economists say the comparison between the two countries is misguided: the problems they face are different. Big foreign loans are Sri Lanka’s primary concern while for Nepal the big worry is a mix of high fuel import cost and erratic remittance. Nepal’s foreign loan-repayments (around $400m due by the end of this fiscal) are peanuts compared to Sri Lanka’s (around $4bn due). But if Nepal does not take drastic steps, it could well go Lanka’s way.

Senior economist Chandra Mani Adhikari says Nepal needs to learn the right lessons. Sri Lanka shows how small and emerging economies can plunge into a deep crisis despite their good economic indicators, he says. That will be the case especially “if their economic policies are flawed and their resources are haphazardly mobilized.” Comparing the economy to a traffic-light system, he says Nepal’s economy right now is in the ‘yellow’ zone and inching toward the dreaded ‘red’ zone.

One big problem in Nepal is lack of coordination on economic policies between concerned agencies. For instance, in the words of Bishwarmbhar Pyakurel, another senior economist, there is little coordination between the National Planning Commission, the Ministry of Finance, and the Nepal Rastra Bank. “These three agencies have competing visions and often encroach on each other’s jurisdictions,” he adds.

So besides drastically cutting the country’s fuel imports and adopting other fuel-saving measures, there is a need to harmonize economic policy-making. What we see instead is the government taking reckless measures like dismissing the sitting central bank governor. This is playing with fire. Hopefully our policymakers realize the folly of doing so before the flares lap up the whole country.

More details, Fixing Nepal’s broken economy and Editorial: Central folly

Fixing Nepal’s broken economy

Nepal’s economy is in a bad shape. Economists are urging the government to take drastic measures even as its options are limited.

Ballooning imports, unpredictable remittance inflow, dismal foreign direct investment (FDI), and sluggish recovery of tourism have depleted Nepal’s foreign exchange (forex) reserves, putting authorities on high alert.

The ongoing Russia-Ukraine war has meanwhile disrupted global supply chains, causing prices of oil and commodities to skyrocket. All these factors have pushed up the country’s inflation and strained its balance of payment and foreign currency stock. A prolonged liquidity crisis has added fuel to the fire. Economists warn of an impending economic crisis.

Meanwhile, Sri Lanka’s financial crisis has caused a degree of panic among the public and there is a risk of the private sector losing confidence. Economists and government officials, however, maintain that Nepal’s economic outlook is much better than Sri Lanka’s. Finance Minister Janardhan Sharma has even claimed that the economy is already recovering.

Senior economist Chandra Mani Adhikari says the Sri Lankan crisis has exposed the vulnerability of smaller countries, irrespective of their growth prospects. “Small and emerging economies could plunge into crisis despite their good economic indicators,” he says, “if their policies are flawed and resources are haphazardly mobilized.”

Borrowing from the traffic-light system, he says Nepal’s economy is currently in the “yellow zone”, a notch below the “red zone”. But he also adds that the country's economy has never reached the “green zone”, he adds.

Dilli Raj Khanal, a former MP and National Planning Commission member, says Nepal and Sri Lanka may differ in the nature of their economic woes, but the trends are similar, which is a cause for concern.

“As in Sri Lanka, politicians here are busy covering up their failures. They want to downplay the crisis instead of introducing coping measures,” he says.

Dwindling foreign reserves is a major concern for authorities. The country’s international currency stock decreased by 16.3 percent to Rs.1.17 trillion by mid-March 2022, from Rs.1.39 trillion by mid-July 2021, according to the April 12 records of the Nepal Rastra Bank. The current forex reserves can sustain imports for just six to seven months.

In the pre-pandemic year of 2018-19, the country’s foreign currency pile had increased by Rs 22.5bn. When the pandemic broke out in 2019-20, forex reserves further increased by Rs 386bn, as imports contracted and remittance flow was still stable.

But when the lockdown was lifted, there was a sudden surge in imports, decimating the foreign reserves.

The current crisis did not happen overnight. Over the past few decades, Nepal’s rate of imports vis-à-vis exports has been going up constantly.

According to the central bank, in the past eight months, merchandise imports increased 38.6 percent, to Rs 1.30 trillion, compared to an increase of 2.1 percent a year ago. Destination-wise, imports from India, China, and other countries increased by 28.1 percent, 36.7 percent, and 75.4 percent respectively.

Nepal spends the most on the import of petroleum products, followed by semi-finished iron and non-alloy steel products and electronic devices including smartphones. The country imported petroleum products worth Rs 182bn in the first seven months of the current fiscal, or Rs 51bn more than earnings from its total exports in the same period.

Surendra Pandey, former finance minister, says the current government is not solely to be blamed for the present crisis, but it should still take it upon itself to improve the forex situation.

“Although the policy of import-restriction will help, that alone cannot ensure sufficient foreign reserves,” he says. He also warns the kind of restrictive measures the government is thinking about could decrease revenues, affecting overall development.

Nepal’s public and foreign debt have also been going up. External debt almost doubled in the past five years. Though the country’s foreign debt liability is not quite as high as that of Sri Lanka, a fast increase means it is starting to strain Nepal’s economy.

The country’s total public debt is 40 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the share of foreign debt is 22.24 percent. Nepal has taken loans from multilateral financial institutions such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, European Economic Community, and Asian Infrastructure Bank. It also has country-specific loans to pay to Japan, China, and India.

Remittance remains the single largest source of foreign currency for Nepal. However, remittance inflow has become unpredictable. The number of Nepali migrant workers going abroad is increasing and their wages in the host countries are also going up, but the remittance flow is still unsteady.

In fact, remittance inflow decreased by 1.7 percent to Rs 631.19 bn in the past eight months against an increase of 8.7 percent in the same period the previous year. Current account also remained at a deficit of Rs 462.93bn in the review period compared to a deficit of Rs.151.42 bn in the same period the previous year, according to a central bank report.

Here, economists point to the government’s policy lapses. In recent times, more and more money is coming through hundi (an informal money transfer system that bypasses banking channels), hitting the government’s income. With the remittance flow constantly fluctuating, policymakers are unsure of the contribution of remittance to the country’s foreign reserves in the next six months.

Tourism also contributes to Nepal’s forex reserves. But the sector has been badly affected by the Covid pandemic. In 2020, foreign currency equivalent to Rs 24.96bn was earned from foreign visitors—70 percent less than the amount for the same period the previous year. While tourism is slowly reviving, it is not bringing in enough foreign currency.

A long-term solution is to introduce sound policies and programs to attract more FDI.

Last year, the Investment Board of Nepal approved Rs 1.08 trillion in FDI. Likewise, the Department of Industry opened up 5,181 industries for FDI, getting commitments totaling Rs 357bn.

Economist Adhikari says despite the big pledges, little foreign investment is coming to Nepal because of pervasive red tape.

“We adopted a one-door policy to fast-track foreign investment but that has failed to bring desired changes,” he says. “The flow of foreign grant has declined as well.”

To tame the outflow of foreign reserves the government has restricted import of non-essential luxury goods like vehicles and is considering steps to minimize fuel consumption, for instance by providing a two-day weekly holiday.

Adhikari says the government should also encourage the use of electricity to reduce cooking fuel consumption.

“To reduce the import of liquid petroleum gas and kerosene, it should assure people of uninterrupted electricity supply so that they can confidently use induction cookers,” he says.

Senior economist Bishwambhar Pyakurel recommends cutting down the use of petroleum products by 50 percent.

Economists also suggest curtailing the illicit cryptocurrency trade and Hundi.

In the long run, they say, the government should work at increasing the productivity of agriculture, creating a conducive FDI environment, decreasing imports and ramping up exports.

It is also important to increase public expenditure, they add.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict, economists say, was a black swan, but its blow could still be cushioned with better coordination among government agencies.

Currently, key bodies like the National Planning Commission, Ministry of Finance, and Nepal Rastra Bank are often working at cross-purposes.

“These three agencies have competing visions and often encroach on each other’s jurisdictions,” says Pyakurel.

He says economic issues have never been a priority of Nepali leaders.

At a time when government agencies should be working together, the central bank governor has been suspended on dubious charges. The government is also yet to remote trade bottlenecks with India and China.

Nepali products are facing non-tariff barriers in the two neighboring countries, but the government has shown no interest in sitting down with India and China to sort things out.

“What we urgently need is a coordinated, comprehensive, and concrete action plan that gives immediate results. The problem right now is that the current crisis is multifaceted, but we are looking at it in a piecemeal fashion,” says economist Khanal.

The confidence of the private sector should be boosted too, he recommends.

“The economy is always based on confidence,” he says. “If the confidence wavers even a bit, it could lead to a serious economic crisis.”

Bishwambhar Pyakurel: No solid plans to fix the economy

Nepal’s economic outlook looks grim. Foreign exchange reserves have dipped alarmingly. Rising imports, decline in tourism revenue, static remittance, and government’s failure to increase capital expenditure have all contributed to this. Some economists have warned Nepal could go the way of the beleaguered Sri Lanka. Is this an alarmist view or could it really happen? Kamal Dev Bhattarai of ApEx spoke to senior economist and former Nepali ambassador to Sri Lanka Bishwambhar Pyakurel.

Let us start with Sri Lanka. What in your view led to its economic crisis?

Sri Lanka didn’t plunge into a severe economic crisis overnight. For a long time, there were clear indications of a looming economic meltdown. This crisis transpired because the Sri Lankan government didn’t take appropriate and timely measures. Unprecedented inflation, dwindling foreign reserves, and mounting foreign debt have crippled the country’s economy.

While some parallels could be drawn between Sri Lanka and Nepal, there is one key difference. Nepal’s foreign debt is comparatively lower than that of Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka has taken out commercial loans at high interest rates, but we haven’t.

As for foreign debt liability, we have to pay $400m by the end of this fiscal. Sri Lanka’s annual foreign debt liability, by contrast, is around $7 billion.

Is Nepal headed towards becoming another Sri Lanka?

So far, the situation in Nepal is under control. But if things were to further deteriorate, we cannot rule out the repeat of the Sri Lankan story here. It depends on how we go about preventing a potential economic crisis.

Nepal Rastra Bank has warned of serious economic consequences if the import of luxury items is not curtailed. For now, Nepal’s current foreign exchange reserves are sufficient to import goods and services for the next seven months. So we should be careful and take right steps to prevent a financial meltdown.

The good news is that remittance inflow is gradually increasing and tourism is also slowly reviving from the beating it took due to Covid-19 pandemic.

So with the cooperation of banks and importers to discourage the import of non-essential luxury goods, our situation can still improve.

What are the reasons for Nepal’s current economic woes?

There are multiple factors. Our foreign reserves are depleting and unnecessary state expenditure is rising, leading to a liquidity crunch. Such challenges can be addressed but there is a need for collaboration among government bodies and the private sector.

Our government and parliament have not prioritized economic issues, which is a cause for concern. The government says financial transactions through Hundi (an illegal remittance transfer system) and the flow of capital through crypto trading have increased. But government agencies are clueless about how to stop them.

While it has discouraged the import of some items, this has not controlled the outflow of money to the desired levels. In a nutshell, this government has no solid plans to fix the economy.

Is this because of a weak leadership?

Yes, 100 percent. Nepal Rastra Bank is handling even fiscal problems. Similarly, the Ministry of Finance is engaging in monetary issues. In many cases, the Ministry of Supply and Commerce is taking unilateral decisions without consulting the Ministry of Finance. The problem is, there are too many leaders, and they are not doing their jobs well. Government agencies are not working in unison.

All ministers in the current coalition government should be held accountable. The current problems cannot be solved without a strong political leadership and without periodic reviews of our economic status and policies.

How much time would it take for Nepal’s economy to recover if we were to take immediate steps?

With a proper policy in place and concerned stakeholders working with determination and energy, it would take no more than six months for our economy to start bouncing back. The current situation is not quite as dire as it has been hyped up to be.

We are facing a fiscal crisis due to mismanagement, failure to reprioritize the areas that need attention, and procedural lapses. There is unnecessary expenditure in government agencies, which needs to be minimized. Consumption of petroleum products should be cut down by around 50 percent because we are spending a huge amount of money on it.

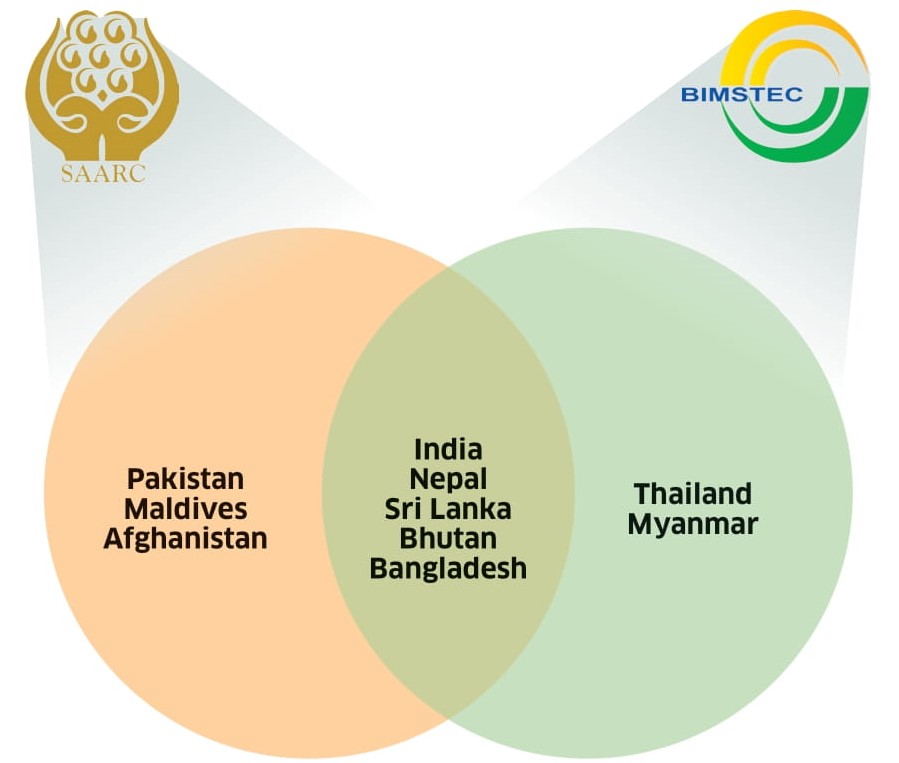

SAARC: The past, present and future

Many reckon the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) is dead and there is no point in flogging a dead horse. Perhaps. As India, by far the biggest South Asian power, is more interested in alternative forums like the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral and Technical Cooperation (BIMSTEC) and the Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal (BBIN) initiative—both without Pakistan—it may be wise to go along with the regional behemoth. BIMSTEC just came up with its charter. Granted. Yet it is not without reason that smaller South Asian countries like Nepal and Bangladesh that played a vital role in SAARC’s formation want to retain and revitalize the regional body.

SAARC came into existence in 1985 at the initiative of Bangladeshi President Ziaur Rahman, with unstinted backing and lobbying of Nepali King Birendra. In the Cold War-era, it was common for the US and the USSR, competing superpowers at the time, to try to create blocs of influence. SAARC came into being partly because of the American desire to keep South Asia out of the Soviet grasp—even as India-USSR relations were warming. But SAARC would not have materialized had the smaller South Asian countries not felt the need to collectively bargain for their socio-economic development with the richer world.

SAARC is dear to the likes of Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Sri Lanka because their leaders have over the years identified with its rationale even as India and Pakistan, the two feuding big powers in South Asia, have not always looked at SAARC kindly.

According to Lailufar Hasmin of the University of Dhaka, “Bangladesh felt that a stable and powerful South Asia was required to ensure its own development. The idea was later crystalized in the organization of SAARC.” Perhaps the same words could be repeated in Nepal’s case.

The idea was that if the region was not consolidated, she adds, its countries could never achieve their potential. This was true in 1985 and it is true today.

Full story here.

SAARC: The original sin or salve?

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) was formed to overcome common regional challenges like pervasive poverty, under-development, and lack of jobs.

Since its inception in 1985, geopolitics in the region and the world at large has drastically changed. But SAARC has made little progress in this time as its key objectives remain unfulfilled.

The 19th SAARC summit, scheduled for Pakistan in 2016, was cancelled after India accused Pakistan of a “terrorist attack” on its soil. The regional body has since been moribund.

Cold War impetus

The Cold War was instrumental in SAARC’s formation. Many regional organizations came into existence at the behest of the Western world at the time, including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). The formation of this Southeast Asian body in 1967 added to the impetus for a similar regional body in South Asia.

In his book ‘Regional Cooperation in South Asia Emerging Dimension and Issues’, Prof BC Upreti of India says that during the Cold War both the US and the USSR encouraged countries across the world to build regional organizations to increase their influence.

Backed by Western countries, many regional organizations such as the Rio Pact, the Organization of American States in Latin America, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization came into being at the time. Their main objective was to protect their politico-strategic interests and to contain the Soviet influence, Upreti writes in his book.

The Soviets also supported the formation of regional bodies of its allies like the Warsaw Pact in Eastern Europe. The two sides in the Cold War wanted to increase their influence through these regional organizations. And the US in particular was keen on getting the countries in South Asia to form a regional organization.

Foreign policy expert Dev Raj Dahal says the talk of regional bodies gained momentum in South Asia in the 1970s.

“The US urged the countries of this region to form a regional body. It first helped form SAARC and later to bring in Afghanistan as its member,” Dahal says.

But it was only in 2007 that the US formally joined SAARC as an observer country. Since then, the US has been continuously expressing its readiness to work on regional integration and connectivity.

China became a SAARC observer country in 2005. It too had of late shown an interest in the regional body, perhaps to expand its sphere of influence in the region.

The other SAARC observers are Japan, South Korea, Myanmar, Mauritius, Iran, Australia, and the European Union.

Regional necessity

The formation of SAARC, however, wasn’t just predicated on Cold War-era politics of regionalism. Its existence was also necessitated by the fact that small South Asian countries needed recognition on the global stage in order to tackle their socio-economic problems. Formation of a community of nations with common interests, they reckoned, would strengthen their voice on the international arena. Together, they could fight poverty and underdevelopment.

Initially, it was Nepal and Bangladesh that strongly pushed for an inter-governmental regional organization at various regional and international platforms, says Dahal.

Addressing the 26th Colombo Plan Consultative Committee Meeting in Kathmandu in 1977, then King Birendra had proposed a regional body to utilize Nepal’s untapped hydropower potential.

At that time, King Birendra had also talked about incorporating China into such a regional body.

But it was then Bangladeshi President Ziaur Rahman who first took the initiative to form SAARC.

Lailufar Yasmin , professor at University of Dhaka, says as a newly independent country, Bangladesh espied the vulnerability of the regional architecture as India and Pakistan were looking beyond the region to ensure their security.

“Bangladesh felt that a stable and powerful South Asia was required to ensure its own development. The idea was later crystalized in the organization of SAARC,” she says.

The idea, she adds, was driven by the concept of regional co-development: if the region is not consolidated, went the idea, its countries could never achieve their potential.

Rehman floated the first concrete proposal before other countries in the region on 2 May 1980. Before that, he had proposed the idea to the then Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai in 1977. He had also shared it with the leaders of Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka during his visits to these countries.

Moonis Ahmar, a Pakistan-based expert on international relations, says formal negotiations among countries to form SAARC began in early 1980s.

“The first meeting of foreign secretaries of South Asia was held in 1981 and the first meeting of foreign ministers in 1983, leading to the first summit of the regional body,” says Ahmar.

At first, both India and Pakistan were skeptical. India was suspicious that smaller countries in the region could use the regional body to gang up against it. Pakistan, on the other hand, saw SAARC as part of an Indian conspiracy to spread its influence in the region.

At the time, King Birendra had played a pivotal lobbying role. After Bangladesh floated the proposal, he dispatched foreign secretary Bishwa Pradhan to the countries in the region to lobby for the formation of SAARC.

In 1980, the foreign ministers of all seven countries met on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly and agreed to prepare a concept note for SAARC.

While preparing the note, the concerns of India and Pakistan were assuaged by picking non-political and non-controversial areas for regional cooperation.

After that, there were a series of meetings to hash out the nitty-gritty.

According to former foreign minister Bhek Bahadur Thapa, King Birendra took the leadership for the formation of the regional grouping.

“Initially, India was reluctant to form such a regional body. It was concerned that smaller neighboring countries could use SAARC to exert collective pressure on it on select issues,” says Thapa.

But King Birendra was dead against unequal treatment of small countries by big ones, says Thapa: “He wanted a regional body to overcome such unequal treatments.”

The collective spirit of small countries was amply reflected in the declaration of the first SAARC summit in Dhaka on 7 and 8 December 1985. It says: “They considered it to be a tangible manifestation of their determination to cooperate regionally, to work together towards finding solutions towards their common problems in a spirit of friendship, trust, and mutual understanding and to the creation of an order based on mutual respect, equity and shared benefits.”

Thanks to King Birendra’s active lobbying, member states also agreed to set up the SAARC Secretariat in Kathmandu.

Since its establishment, Nepal has been trying to make it a result-oriented organization. The country has also been serving as the chair of the regional body since 2014.

With the 19th SAARC summit indefinitely postponed over India-Pakistan tensions, Nepal has been urging the two countries to create a suitable climate for the summit. But nothing has come of it.

Pakistan has accused India of obstructing the SAARC process. India, meanwhile, doesn’t seem interested in taking SAARC forward. It has instead prioritized the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), of which Pakistan is not a part.

Already, many Indian international relations experts and leaders see BIMSTEC, an international organization of seven South Asian and Southeast Asian countries, as an alternative to SAARC.