Twin private bills: Indian interest or Madhesi aspiration?

The Janata Samajbadi Party, Nepal (JSPN) and some Nepali Congress (NC) lawmakers have pushed separate constitution amendment bills with the intent of addressing the pending concerns of the Madhesi people. The chances of either of these bills getting parliamentary approval are slim. Even the leaders who registered the bills are not optimistic.

As the government is not in a mood to address such private bills in the current budget session, they may not even be tabled in the full house. Right now the parliament is busy discussing the fiscal budget and the bill related to redrawing Nepal’s map.

The JSPN and NC leaders who registered the bills say the objective is to keep the Madhesi demands alive. Both JSPN and NC see Madhes as their base area and are looking to increase their appeal among common Madhesis.

JSPN leaders say their bill is aimed at creating momentum for a possible movement in the Madhes after the lockdown. According to Keshav Jha of JSPN, the new movement will incorporate all marginalized communities who have been deprived of their rights in the constitution. “We will launch a nationwide campaign for constitutional amendment through an alliance called the Rastriya Mukti Aandolan,” he says.

In order to lay the ground for another Madhes movement, two Madhes-based parties—the RJPN and Samajbadi Party Nepal—had recently joined forces to form the JSPN. Both the parent parties had already withdrawn their support to the government, blaming it of neglecting their demands. They had waited for over two years with the hope that PM Oli would amend the constitution as per their demands—to no avail.

Many views

Without the ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP) on board, it will be impossible to secure the two-thirds votes needed for constitutional amendment. Though the NCP co-chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal is said to be positive about the demands of Madhes-based forces, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli is not. There are differences between Oli and Dahal over both Madhesi and Janajati demands. Oli believes there is no need to amend the constitution before the next elections, while Dahal is of the view that the ruling party would do well to accommodate the sentiments of the identity-based forces.

PM Oli has repeatedly said, without elaborating, that the national charter would be amended only ‘on the basis of necessity and relevance’. As the constitution has not completed even its first five-year election cycle, Oli and those close to him think, it is too early to make substantial changes. Oli instead wants to engineer a split in Madhes-based forces to strengthen his own party’s position in Madhes.

Meanwhile, both the NC and Madhes-based parties agree in principle that the constitution should be amended, but they are somewhat divided on the contents of amendment.

The amendment bill tabled by the JSPN has several provisions related to language, citizenship, proportional representation of women in state mechanism, and forming a powerful body to investigate the properties of those who hold high positions. Madhesi leaders reckon the current anti-corruption body, the Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA), is incapable of investigating high-ranking government officials and politicians.

The NC has a position similar to Madhes-based parties on some issues. The bill registered by its lawmakers seeks to ease the process of providing citizenship to foreign women married to Nepali men, guarantee proportional representation of women in state bodies, and increase women’s representation in provincial assemblies. To address the demand of Madhes-based parties on re-demarcation of the borders of federal states, the NC wants a powerful federal commission.

The Madhes-based parties too have asked for a commission to re-think federal border demarcations. Their other demands include easing the process of citizenship for foreign women marrying Nepali men, proportional representation of women from all communities in state mechanisms, more rights to provincial government to make laws and mobilize local bodies, and granting executive rights to the deputy speaker in the speaker’s absence. All these, the Madhes-based parties say, should be done via a powerful federal commission.

Madhes-based leaders say the amendment bills are largely symbolic. “We are not hopeful about a favorable amendment,” says NC lawmaker Amresh Kumar Singh, one of the NC lawmakers to register the amendment bill on his party’s behalf. “Our goal is to expose PM Oli and NC President Sher Bahadur Deuba. They join hands on issues of vested interest. And yet when it comes to amending the constitution to address Madhesi people’s demands, they drag their feet.”

No Indian hand

In the past, India had openly backed Madhesi parties’ demand for constitutional amendment and had even enforced a blockade on Nepal to press for it. But the blockade backfired, and India has since maintained silence on Madhesi issues.

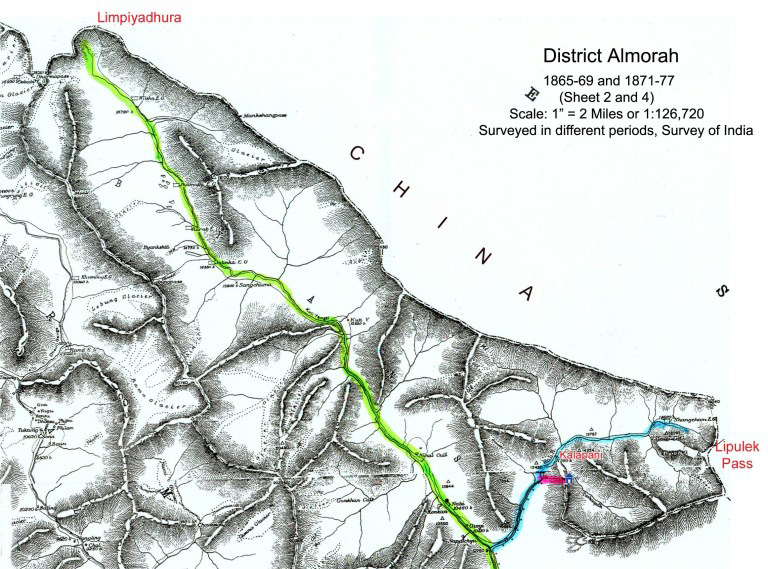

There are speculations that India lobbied with the Madhesi leaders to register their own amendment bills in order to thwart, or at least delay, the charter amendment that would recognize the 372 sq km of Limpidhura, Lipulekh and Mahakali as Nepali territory.

But a senior Madhesi leader requesting anonymity says India has nothing to do with the amendment bills concerning Madhes. “When the Oli government came up with a bill relating to Nepal’s new map, we decided to push our bill simultaneously,” he says.

India considers constitution amendment a bargaining chip with Kathmandu, he adds, and is not supportive of Madhesi demands.

Political analyst Vijaya Kant Karna too does not espy Indian hand behind the twin bills “The current Madhesi leadership still believes their demands can be resolved peacefully,” he says. “They want a win-win solution by convincing PM Oli. The feeling is that if PM is committed to stability and prosperity, he should take Madhes-based leaders into confidence.”

Far-reaching impacts of lockdown on Nepali society

A United Nations Development Program (UNDP) survey of 700 businesses and 400 individuals, and consultations with over 30 private sector organizations and government agencies, came to a sobering finding: “The Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted supply chains, shut or threatened the survival of small and informal enterprises, and made people highly vulnerable to falling back into poverty through widespread loss of income and jobs.”

This situation can be tackled only with swift and extreme measures. The consensus is that the government decision to continuously extend the lockdown without seemingly exploring other alternatives is dead wrong. (Even though the lockdown seems to have eased up a bit of late, the country is far from being fully open to business.)

Sociologist Mrigendra Kumar Karki fears complete and partial lockdowns, which are likely to continue in the foreseeable future, will further widen the gap between haves and have-nots, as it is the poor who will suffer disproportionately. “There must be comprehensive short- and long-term studies on the multifarious impact of the lockdowns, and policy measures swiftly enacted to mitigate the effects,” he says.

Karki also points to the political implications of the extended lockdown. He argues people are gradually losing their trust in the government. “There is a feeling that the government won’t be able to help them if they get infected. People at the community level are themselves preparing to deal with the virus,” Karki says. He fears the mistrust between the state and its people will widen in the coming days.

In the Initial days, the lockdown disproportionately impacted daily-wage earners. The government tried to address the problem by providing them food-grains through local governments. Now, the lockdown is starting to weigh heavy even on those in organized sectors who rely on monthly salary for their livelihoods. Many private organizations have either not paid their staff, or delayed the payment. To take just one example, of around 500,000 people employed in tourism, many have already lost their jobs while others are on unpaid leave.

The extended lockdown is harming all sectors. “With almost 85 percent of the working population in Nepal informally employed, such work avenues provide no significant assurance to the informal economy. It instead has possibly worsened poverty, put food security at risk, increased social tension, and threatened mental health amongst informal workers,” says the aforementioned UNDP survey titled Rapid Assessment of Socio-Economic Impact of Covid-19.

Long, dark tunnel

Dr Kapil Dev Upadhyaya, a consultant psychiatrist at Center for Mental Health and Counselling (CMC-Nepal), says people are getting increasingly frustrated at the prospect of having to stay cooped up in their homes indefinitely.

“It is not only about the lockdown. People seem worried they may not be treated if they catch the virus. They have little faith in our shambolic healthcare and quarantine systems,” he adds. As a result, Upadhyaya foresees many more “mental and physical health problems” down the line.

The number of suicide cases has increased. According to the data provided by Nepal Police, 1105 people committed suicide between March 24 and May 30, a daily average of 16.25 compared to the average of 14-15 before the lockdown.

As the economic hardship starts to bite, the fear of looting, burglary and other forms of social crimes has increased, too. Such incidents are more likely in rural areas with low presence of security forces.

There is also an urgent need to provide jobs to the unemployed. In 1996, when the Maoists began their armed insurgency, they had recruited large numbers of unemployed people from rural areas. “Today, a failure to create jobs for the youth could once more threaten Nepal’s political stability,” says asks Hemant Malla, a retired Deputy Inspector General of Police. Notably, the Maoist splinter group led by Netra Bikram Chand has already launched an armed insurgency.

As the number of infected people is increasing by the day, chances of immediately and completely lifting the lockdown are slim. Other countries are gradually opening up their economy. In our case, there has been a continuous lockdown starting March 24—and the government is struggling to justify it. Unless there is a radical shift in the thinking of state authorities, things will only go from bad to worse.

Nepal presses claim on Kalapani, settlement still elusive

The government of Nepal has finally tabled a bill in the federal lower house with the intent of amending Schedule-3 of the constitution in order to include the new territorial map in the national emblem. After the passage of the bill, the new map covering Kalapani, Lipulekh and Limiyadhura areas will become an integral part of the country’s constitution.

As per parliament procedures, lawmakers will have seven days to come up with amendment proposals. After that, the parliament will discuss possible amendments in the bill. There will then be theoretical discussions, followed by clause-wise discussions, before the bill is put up for a final vote.

If the parliamentary parties want to delay the amendment process, there are ways to buy time. For instance, the speaker can form a special cross-party committee to discuss the matter. But says a source at the Parliament Secretariat, “This time, as nearly all the parties have agreed to amend the constitution at the earliest, there could be no need for such committees.”

Except for the Rastriya Samajbadi Party, Nepal (RSPN), other parties are expected to vote in the bill’s favor. The RSPN has said that their long-standing demands related to the constitution should also be simultaneously addressed, and it has tabled a separate constitution amendment bill to that effect. The Nepali Congress (NC), the main opposition that had earlier sought some time for intra-party discussion, has already decided to vote in the bill’s favor. As things stand, the bill will garner two-thirds vote in the parliament even if the RSPN votes against it.

Cramped for room

Political analyst Chandra Dev Bhatta says that once the bill is approved by the parliament, the new map will not only be official but also constitutional. “The said territory then becomes an integral part of Nepal, which, as per the constitutional provisions, will have to be protected by the Nepal Army in case of outside aggression. But we also have to acknowledge that Kalapani has for long been a subject of Nepal-India discussions, and the said territory is still under Indian possession.”

The likely amendment will reduce Nepal’s room for flexibility on the border issue. Major political parties are united on the issue. Given the enormous public support for the bill, it will be hard for any of them to back away. Knowing that a majority support may not be easy to get in the future, both the government and opposition parties are intent on pressing ahead. In public, they affirm that they will convince India to withdraw its troops from Kalapani, as Nepal has ample evidence to establish its claim over the territory.

“India should behave responsibly. It never paid attention to Nepal's repeated requests for talks. For Nepal, there really was no other option,” says Bhatta, adding that the border dispute could further strain Nepal-India relations.

Meanwhile, constitutional expert Bipin Adhikari seconds Bhatta’s view that the amendment will make negotiations with India tougher. “The lower-level negotiators will not be in a position to compromise when the areas under discussion are constitutionally recognized,” he says.

Mixed signals

India is sending mixed signals over its willingness for talks. On May 9, India stated that “both sides are also in the process of scheduling foreign secretary-level talks which will be held once… the two societies and governments have successfully dealt with the challenge of Covid-19 emergency.” But then on May 20, India urged the Nepali leadership to “create a positive atmosphere” for border dialogue.

Following this, on May 28, India stated its openness to engaging with all its neighbors on the basis of mutual sensitivity and respect, and in an environment of trust and confidence.

According to sources, India urged Nepal government to forestall the amendment, as it would narrow down the possibility of talks. For now, the Nepali side wants talks at the prime ministerial level. But right now foreign secretary-level dialogue is the only agreed mechanism to look after the disputed territory.

There is no discussion yet on alternatives for resolving the border dispute. According to government sources, Nepal is not going to stick to its stand of asking India to withdraw its troops from Kalapani as “the land belongs to Nepal”. The Nepali side reckons there is enough evidence to support Nepal’s position.

Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali is publicly urging India to withdraw its troops from Kalapani. Officially, the Indian government has not spoken on solutions. Following the protests in Nepal over the 2015 India-China bilateral statement on trading through Lipulekh in Kalapani, the Indian side had informally floated a proposal of land swaps before Nepali leaders to resolve Kalapani. But the Nepali leaders rejected the offer.

In his article published on May 26 in The Wire, Ashok K. Mehta, a retired Major General of the Indian Army, said: “Only a political resolution of the dispute is the way forward. Although still not at that stage, both countries can consider the concept of joint sovereignty.”

Multiple hurdles

Experts in Nepal say it won’t be easy to wrest back lost territories. To start with, as it is impossible for Nepal to lay a claim to the territories militarily, it has no option but to coax India to the negotiating table. But with the mood in New Delhi hardening, that may not happen anytime soon.

Yet all hope is not lost. Talking to an Indian television channel on March 31, India’s Minister for Defense Rajnath Singh said the chances of Nepal and India, who are like “family members and relatives”, finding an amicable solution were still high. So far India’s stand in future discussions, if and when they happen, remains unclear.

When will Nepal and India sit for talks?

After the publication of its new political map including Kalapani, Lipulekh, and Limpiyadhura, the government of Nepal has ramped up efforts to start formal talks with India. Nepali Ambassador to India Nilambar Acharya has been instructed to reach out to Indian officials to create an environment for such talks.

Nepal is of the view that a high-level virtual meeting could start even amid the Covid-19 pandemic in order to give a message that dialogue has begun. Such a process, for instance, could be initiated via a phone conversation between the two foreign ministers.

There is also pressure on the Indian government to sit for dialogue. Right now the foreign secretary-level dialogue is the only available bilateral mechanism to take up boundary disputes. Nepal had proposed two dates for foreign secretary-level talks after India came up with a new political map in November. India ignored these requests.

The chances of dialogue between the two countries in the near future appear slim. Retired Indian diplomats who spoke to APEX said there could be no dialogue in the current tense situation.

India has also put forth conditions for talks. The May 20 press statement of India’s Ministry of External Affairs says, “We hope that the Nepalese leadership will create a positive atmosphere for diplomatic dialogue to resolve the outstanding boundary issues.” India, however, has not clarified how such “positive atmosphere” may be created. In a previous statement, India had said that it was ready for talks after the end of the Covid-19 crisis.

Unlike the past

Sooner or later, the two sides will have to sit for talks. Unlike in the past, the Nepali society and political parties are united on the border dispute. “During the time of the Mahakali Treaty in 1996, Nepali polity and society were divided. They were also divided at the time of constitution drafting in 2015. The situation is entirely different now,” says geopolitical analyst Tika Dhakal. This, in his view, has given the Nepali government greater confidence to negotiate. “There should be negotiations at all possible levels. It is time to activate all bilateral mechanisms, including the meeting of foreign secretaries,” he advises. A series of discussions at the bureaucratic level, he adds, can lay the ground for higher-level talks.

Dialogue can take place at various levels. The two foreign secretaries can immediately meet. The Nepal Army (NA) may also have a role given its ‘special relationship’ with the Indian Army. During the 2015-16 blockade, the Nepal Army had played the crucial role of getting its Indian counterpart to successfully lobby with the Indian government to lift the blockade.

Former Brigadier General of Nepal Army Umesh Bhattarai differs. “In 2015, the Indian Army was not involved in the blockade but in Kalapani it is directly involved. So army-level talks is not a viable option this time,” he says. Bhattarai is of the view that the Nepal Army should rather show its presence in the Kalapani area.

Where’s the will?

“We have sufficient proof that these territories belong to Nepal. So why not try to convince the Indian side on the negotiation table?” Bhattarai asks. After the incorporation of the new map in the constitution, it will have the ownership of all parliamentary parties and they will be bound to have a common stand on Kalapani. Sufficient proof and a common stand, Bhattarai reckons, will help Nepal’s cause at the negotiating table.

On the other hand, India is hardening its position. In the past, India had recognized Kalapani as a disputed territory. But after the publication of its new political map in November last year, India claims this is now an entirely Indian territory.

Nepal on the other hand is confident that it will be able to convince India of why the new map had to be published. Reportedly, Prime Minister KP Oli is not in a mood to further provoke India and wants immediate dialogue to defuse the tension.

Boundary disputes are an old problem between the two countries. Experts say this is the perfect time to resolve it, as both the prime ministers have strong mandates. There is strong support in Nepal for Oli government’s efforts to resolve the border issue, and Modi, likewise, is in a position to make hard decisions. But then do they have the political will to settle Kalapani?

Indian media messes up Nepal again

There has been outrage in Kathmandu over the jingoistic and belittling tone of Indian media following Nepal’s publication of a new political map of the country including Kalapani, Lipulekh, and Limpiyadhura. Indian TV channels are now openly saying that Nepal did so at Beijing’s behest and the country has thus become a ‘puppet of China’.

Indian TV news channels are notorious for exaggerating and sensationalizing issues. In the case of Nepal-India relations, they also seem poorly informed. And this is not the first time something like this has happened.

For one, they seem short on hard facts about border issues between India and Nepal. This is perhaps because in normal times they rarely give much importance to Nepal-India relations. But when something significant happens, they rush to run news stories, host television shows, and publish commentaries.

Says Tara Nath Dahal, chief executive of Kathmandu-based media think tank Freedom Forum: “They often lack background information on what is happening between the two countries. When something big happens, they manipulate it as they see fit.”

The way it is being portrayed, many Indian media houses seem unaware that Kalapani and Susta are two disputed territories that Nepal has for long been trying to resolve with India. Most reports say Nepal damaged the bilateral relation by issuing a new political map. But they fail to mention that India too had issued a controversial map in November without consulting Nepal, and that the Indian defense minister had recently inaugurated a road passing through disputed territories.

In recent years, the Indian media have been recalling their Kathmandu-based correspondents and closing down bureaus, indicating that Nepal no more falls under their radar in normal times. This has hampered the flow of information from Kathmandu to media operators in Delhi.

“In the past, full-time correspondents and bureaus used to send authentic information from here, which helped Delhi understand Kathmandu better,” recalls Dahal. There are now very few journalists in New Delhi who exclusively cover comparably smaller countries like Nepal. Foreign correspondents are mostly occupied, and perhaps understandably, with big powers such as China and the United States.

Media expert and educator Kundan Aryal says Indian Hindi-language TV channels often run unconfirmed reports. Besides, the Indian society has no access to Nepali media products. Those interested may get information from a few of Nepal’s online English news portals. Yet they have almost no access to the vast Nepali language media.

On the other hand, Indian online portals and television news channels are quite popular in Nepal. “If they cared about what the Nepali media is saying, they would have found a way to know. In that case, they could also better understand Nepal,” Dahal says.

One problem with Indian media operators, according to Dahal, is that they often reflect Indian hegemonic attitude and don’t treat Nepal as a sovereign country.

Meanwhile, Aryal reckons the content of Indian media is often doctored. “They run such content incessantly on TV, newspapers, and online portals. It has earned them an image of unreliability and jingoism,” he says.

Nepalis had a taste of how the Indian media worked when their TV crews arrived here in droves in the aftermath of 2015 earthquakes. According to Aryal, they started behaving like the public relations departments of the Indian Army and PM Modi right from the beginning. “They produced news as if Nepal had already collapsed and Modi, as the savior, had sent the Indian army to rescue the country.”

An Indian TV reporter went so far as to direct the camera at somebody trapped inside the rubble and ask, “How are you feeling like that?” The visitors faced harsh criticism and public anger in Kathmandu. Nepali youths started a social media campaign with the hashtag #GoBackIndianMedia, which instantly trended.

Indian media has earned infamy on other occasions also. “Indian TV channels have sensationalized issues during Indo-China border standoff of 2017, Indo-Pak tension about Kashmir of 2019, and during the current Nepal-India border dispute. They cook up conspiracy theories and baseless arguments,” says Bhanu Bhakta Acharya, a media researcher at Universality of Ottawa, Canada. Political talk shows run by Indian TVs undermine professional values of journalism such as accuracy, balance, credibility, decency, and fair play, he adds.

“In principle, media talk shows should promote mutual understanding between or among the parties in discussion,” Acharya says. But Indian TV shows feature more sensational and angry exchanges. They create a toxic environment among debating parties and end any chance of reconciliation, according to Acharya. “The hosts of these Indian TV channels speak as if they are government spokespersons, they know everything, and there is no room for further discussion."

Onus on India

After the low of the 2015-16 blockade, Nepal-India ties have again hit rock bottom following the latest disputes over some 372 sq km of land on the border abutting the Kali River. India built a road through the Lipulekh Pass without consulting Nepal. It has also been stationing its army at Kalapani since the early 1950s, purportedly to monitor Chinese movements in Tibet. The latest disputes came to a head when the Indian army chief pooh-poohed Nepal’s claim over Kalapani and Lipulekh, saying that they fall entirely within India, and accused Nepal of raising the issue at China’s behest.

Yet most Nepalis, and their government, are as angry with China as they are with India. They think China should not have allowed India to unilaterally build the road on what China considers a tri-junction between Nepal, India and China. Even worse, did the road have Chinese blessing, they suspect? After Nepal published a new national map incorporating all the disputed territories, China said it hoped both Nepal and India would stop all unilateral activities. It added the dispute over the Kalapani region in particular is entirely up to Nepal and India to settle.

Says Lin Minwang, Professor at Institute of International Studies at Fudan University, who closely follows China’s South Asia policy, “India has territorial issues with all its neighboring countries, and has always insisted on a tough position on territorial disputes, which is not conducive to a stable and peaceful environment.” Instead of solving its outstanding issues with Nepal, he added, India is trying to deflect the blame by accusing China of instigating the protests in Nepal.

The bargain India and China struck in 2015 while deciding to open trading via Lipulekh is still shrouded in secrecy. There is a suspicion in Nepal that since India offers China huge markets at its doorstep, Beijing will silently support India’s bid to link the two regional giants, including through passes like Lipulekh. China will have to do a lot to dispel this doubt in the days ahead.

Nepal-India EPG member Surya Nath Upadhyay thinks as Nepal has in the past supported China in difficult times, Nepal can expect reciprocal support. “We should not hesitate to seek active support of China to resolve the Lipulekh dispute. Without pressure from China, India will not agree to its resolution.”

But as the instigator of the current dispute and as the party that has been reluctant to settle Kalapani for many decades, the onus lies on India to create a conducive climate for Nepal-India talks. Ultimately, a workable solution will have to come through dialogue; there is no other way out. Meanwhile, we hope high-ranking officials in both Nepal and India, and their influential voices in the media and the society, refrain from making incendiary remarks to further complicate the situation. Here is a chance for India to prove its Nepal ties are indeed special.

MCC not related to IPS: Senior US official

Kathmandu: The United States has said that the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) established in 2004 is completely unrelated to President Donald Trump’s vision of an open and free Indo-Pacific.

Speaking in a special ZOOM press briefing, Alice G. Wells, Acting Assistant Secretary, Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs said that there has been a great deal of disinformation about the America assistance to Nepal.

Over the latest debate on the MCC, she said, it’s “…much more about internal politics in Nepal, and I would certainly hope that the leadership of your nation who negotiated this agreement… brought in all major political parties during the negotiations over three years…. that the leaders of your nation are going to stand up for the people of Nepal and move forward with the MCC.”

Asked about the speculation that China does not want Nepal’s endorsement of the MCC, which in turn is the reason for the opposition against it from a section of Nepal’s ruling party leaders, she said, “Government of Nepal is sovereign… it does not take dictation from China. It will do what is in the best interests of its country to advance the economic welfare of its people.”

“This program is specifically designed by [the US] Congress to provide poverty alleviation through creating greater confidence in a country’s ability to implement economic programs that are designed to unlock the blockages to growth,” she added.

“The MCC, in which Nepal government also committed another $130 million in additional funds above the $500 million that we seek to allocate, it’s designed to promote hydroelectricity transmission, including sales across border, and also to reform the road structure so that you open up the economy, potentially, to increased foreign direct investment.

“The fact that this grant assistance—not a loan, grant assistance—has become a political football is disturbing,” she said.

China’s silence adds to Nepal’s woes on Lipulekh

Indian Army Chief Manoj Mukund Naravane tried to downplay Nepal’s protest over the Lipulekh road as undertaken “at the behest of someone else.” His statement raised many eyebrows in Nepal. The Indian general was clearly hinting at China. Yet the Nepali government and the people have been as surprised by China’s silence over the issue as they have been with India’s land grab in Kalapani.

Before 2015, Nepal expected China’s active support in the resolution of the Kalapani and Lipulekh disputes. But that year India and China agreed to boost border trade via Lipulekh, without consulting Nepal. Traditionally, Nepal has seen Lipulekh as a tri-junction point between Nepal, India, and China.

The joint statement issued on 15 May 2015 during Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to China says: “The two sides agreed to hold negotiations on augmenting the list of traded commodities, and expand border trade at Nathu La, Quiangla/Lipulekh pass and Shikki La.” Erstwhile Nepal government led by Nepali Congress President Sushil Koirala had immediately sent diplomatic notes to India and China, expressing its displeasure over the agreement.

China promptly responded but India remained silent. According to Foreign Ministry sources, China said that there was room for improvement, and if necessary, it was ready to revise the agreement. Many want the government to send a diplomatic note to China again.

Foreign policy experts in New Delhi reckon this is a matter purely between Nepal and India, and there is no point in dragging in China. A retired Indian diplomat, requesting anonymity, says: “The current dispute is not about fixing the tri-junction, it is about the source of Kali River. So Nepal and India should immediately sit for dialogue to seek a solution.”

Lin Minwang, Professor at Institute of International Studies at Fudan University, who closely follows China’s South Asia policy, says, “India has territorial issues with all its neighboring countries, and has always insisted on a tough position on territorial disputes, which is not conducive to a stable and peaceful environment.” On the other hand, he adds, China has resolved most of its border problems with the 14 countries with which it shares borders. Lin thinks India should learn from China’s “experience and political will” in resolving border issue with its neighbors. He says that it is ‘unwise’ of India’s high-ranking officials to imply that China is behind the current border dispute between Nepal and India.

Old wound

The issue of settlement of tri-junction between Nepal, India, and China has been pending since 1963 when Nepal and China signed a border agreement. “When Nepal and China settled the boundary dispute, the relation between India and China was not cordial,” says former foreign minister Bhek Bahadur Thapa. “So the issue of tri-junction could not be settled. There was consensus that it would be settled at an appropriate time, which never came.”

Kathmandu expects China, a stakeholder in this dispute, to tell India that the new road can come into operation only after addressing Nepal’s sovereignty and territorial integrity concerns. A former Nepali diplomat says that in 2015, China overlooked the issue when it signed the agreement with India, and China will now have to speak up sooner or later.

Member of Nepal-India Eminent Persons’ Group (EPG) Surya Nath Upadhyay says that the current dispute cannot be resolved without talking to China. “As we are yet to fix the tri-junction, China’s involvement is necessary,” he says.

Political leaders are also pressing the government to talk to China. Speaking at a parliamentary committee meeting, ruling Nepal Communist Party Co-chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal said: “Lipulekh has emerged as a tri-lateral issue, so it is very difficult to resolve it bilaterally.”

China has not yet spoken about India’s road inauguration. However, when India put Kalapani within its territory in its new political map in November 2019, Wang Xiaolong, spokesperson at the Embassy of China in Kathmandu, had said, “The Chinese side wishes Nepal and India could resolve their territorial disputes on Kalapani through friendly consultations and negotiations.” The statement also said that China always respected the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Nepal.

There are reports that the government is preparing to hand a new protest letter to China in this regard, but a final decision on this is pending.

Missing Chinese pressure

In the past, too, Nepal had sought China’s help on the dispute. In 2005, Nepal’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs raised the issue of 2004 India-China agreement on border trade. Nepal also asked the visiting Chinese military delegation led by Major General EI Hujeng to help resolve the Kalapani dispute with India. (The armies of Nepal and China used to have top-level discussions on Kalapani and Lipulekh back in the 2000s.)

Nepal has sought the help of India too. Lipulekh Pass has been a recognized trade and pilgrim route between China and India since 1954, and there have been several agreements between them on this route.

The border dispute was removed from government agenda with the formation of Nepal-India Eminent Persons Groups (EPG) in 2016. The two governments had agreed to settle outstanding issues, including border disputes of Kalapani and Susta, in line with the EPG's recommendations. But with India’s reluctance to accept the final EPG report, things have not moved forward.

Nepal has been pressing India for talks after the latter published the political map including the Nepali territory of Kalapani within its borders in November 2019. Nepal has twice proposed foreign secretary-level talks, but India has snubbed both requests.

EPG member Upadhyay thinks that as Nepal has in the past supported China during difficult times, we should expect reciprocal support. “We should not hesitate to seek active support of China to resolve the Lipulekh dispute. Without pressure from China, India will not agree to its resolution.”